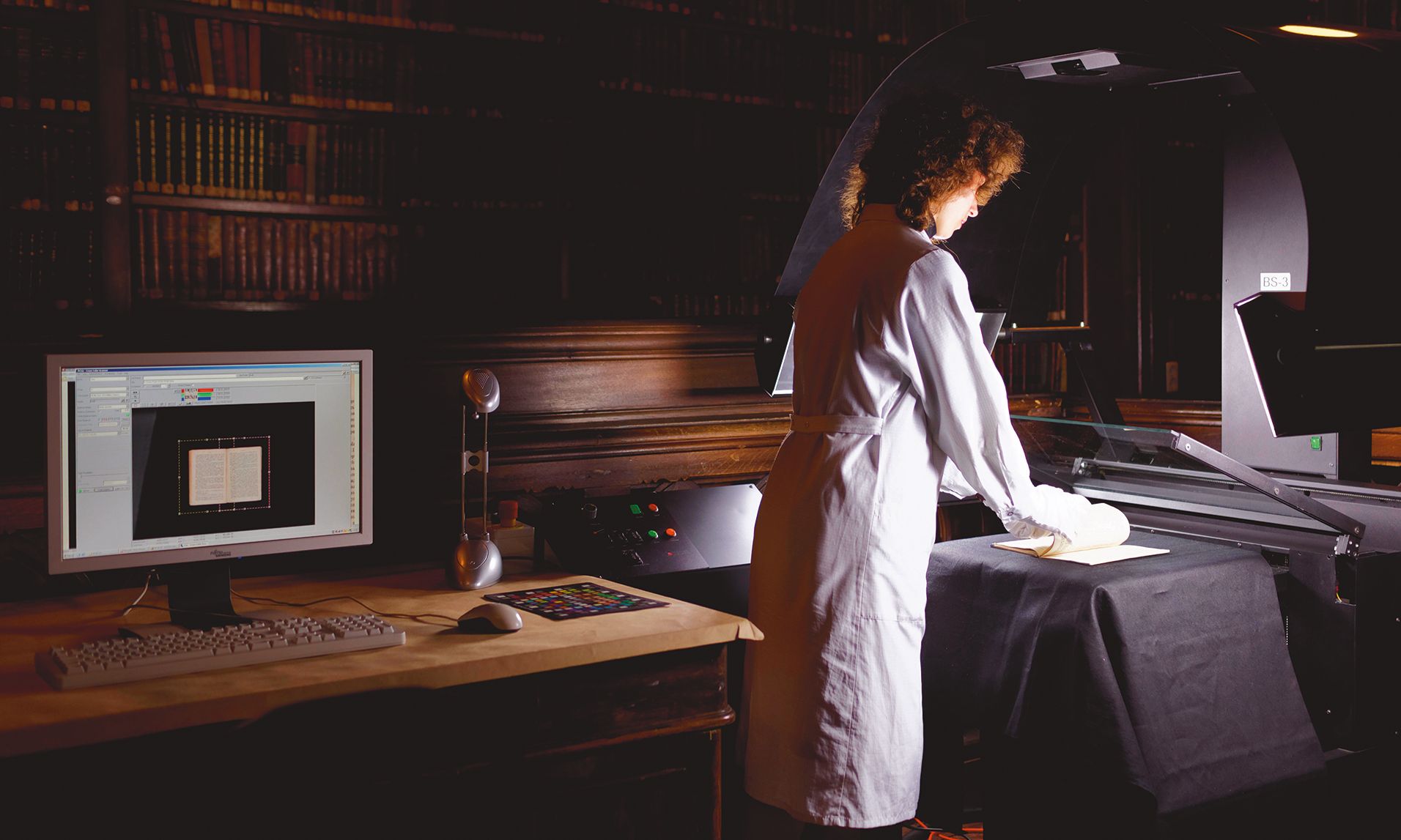

Most museums now digitise their collections—but should they keep these digital artefacts if the original objects are repatriated? Lilyana Vynogradova/Alamy Stock Photo

The rate of artefact repatriation—objects being returned to their country of origin, often from museums—has been accelerating in recent years. These objects may have been housed in foreign collections for centuries and, increasingly, have likely been added to museums’ digital inventories and detailed on websites for the world to see.

While the digitisation of museums’ collections may enable the public greater accessibility to artefacts, it raises questions about the possibilities of digital repatriation: returning digital images, research data, and 2D and 3D digital models along with the physical objects themselves. When items are returned to their source communities or institutions, is the associated digital data being repatriated along with them? Where do museums currently stand on digital repatriation?

Not every returned object has a publicly accessible webpage or associated digital data, but institutions are increasingly moving to digitise their collections, spurred on further during the Covid-related lockdowns when no one could access museums in person. As well as internal databases and public platforms, websites such as Sketchfab and TurboSquid host thousands of 2D and 3D object models, including digital object data created by private and public cultural heritage institutions. Where does this information belong?

Currently, many museums choose to remove the information of repatriated objects from their public platforms. Such is the case for the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC when it returned a Benin bronze cockerel belonging to Nigeria in October 2022. The Cleveland Museum of Art (CMA), on the other hand, hosts a webpage documenting all the art it has deaccessioned since 1998, showing works’ former titles, accession numbers and creation dates.

But which strategy is better? Retaining a publicly accessible deaccessioning record promotes accountability but, on the other hand, such records may be inconsistent with those of an object’s new owner, and maintaining them may promote an understanding that a museum still considers itself an owner of the object. Some institutions have piloted a model of returning objects to their source community but keeping a 3D digital model-replica at the institution for researchers, which raises further questions about ownership and access.

Recent research has explored how collections’ information systems and databases present a number of issues for communities whose cultural heritage and traditional knowledge was acquired and held unethically. The US project Local Contexts supports Indigenous communities in such situations to “manage their intellectual and cultural property, cultural heritage, environmental data and genetic resources within digital environments”, according to its website. It creates “Traditional Knowledge Labels”, including those related to provenance, noting community-specific regulations regarding access and use of knowledge. However, their use in digital object collections focuses mostly on audio, video and paper materials, and its integration into object databases has revealed some user experience design problems.

While some museums consider the content that they have produced relating to an object to be part of its intellectual property, many are willing to repatriate digital data. “Assets such as imagery, photogrammetry or research is shared with the party to whom the object is transferred, when it is transferred,” says a spokesperson for the CMA. The Brooklyn Museum explains that “since the object data is part of the intellectual property and cultural heritage of source communities”, an object’s associated digital materials may be returned as well, if requested. A spokesperson for the Getty Museum in Los Angeles also says that the museum will return digital files on request.

But because the concept of digital repatriation remains relatively new, few source communities and institutions realise that they can request object data, and even fewer museums have incorporated digital repatriation into their collections management policies. Helen Robbins, the repatriation director at the Field Museum in Chicago, highlights a widespread issue: “While, of course, the museum’s collections management policy and our procedures address the repatriation of tangible items and ancestral remains, they do not specifically address digital repatriation.” Similarly, a spokesperson for the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York notes that “the museum is happy to share images and object data, but it is not a formal part of the transfer process”.

Navigating the return of physical objects is a challenge for both source communities and museums—but if policies are not created for digital data and legacies of repatriated artefacts, institutions could be setting themselves up for further requests down the line.

• Emma Cieslik is a collections contractor at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of the American Indian. The views in this article are the writer’s own