[ad_1]

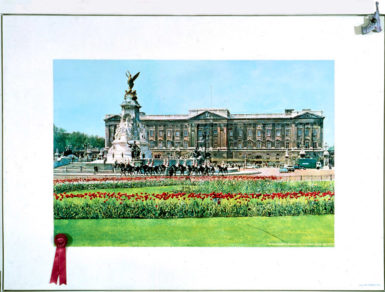

An image from the auction of Morley’s Buckingham Palace with First Prize in 1974.

COURTESY SPERONE WESTWATER

One would not necessarily think that the mysterious street artist Banksy and the esteemed figurative painter Malcolm Morley would have much in common, but it turns out they do: Banksy’s recent auction stunt at Sotheby’s in London—the shredding of his painting just as it sold for $1.4 million—was directly in the lineage of a prank that Morley pulled off almost half a century earlier, in 1974, when he attacked one of his own paintings as it came up for auction in Paris.

Collector Andy Hall recalled the incident at Morley’s memorial earlier this month at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York (the artist passed away in June at the age of 86):

In 1974 one of Malcolm’s paintings came up for auction in Paris. The work was called Buckingham Palace with First Prize which he had painted in 1970 immediately after completing Race Track. This work depicted a banal post card image of Buckingham Palace with some kitschy municipal flower beds in the foreground. It had been commissioned as part of a group of artworks by an association of florists. Malcolm had ironically subverted the painting by the Duchampian addition of a mass-produced rosette—the type doled out as prizes in flower arrangement competitions—which he had attached to the bottom left of the painting.

As chance had it, Malcolm was in Paris at the time of the auction for the opening of an exhibition of his paintings at a commercial gallery. Malcolm put out the word that something would happen at the auction. On the evening of the sale Malcolm turned up at the auction house in a tuxedo bearing a water pistol full of purple ink. His plan was to spray the word “faux” (or fake) on the painting. The auction house, however, had gotten wind of the mischief and had covered the painting with a thin sheet of plastic, thus thwarting Malcolm’s plans. As the auction house porters tried to hustle the painting out of the auction room Malcolm rushed forward and, while shouting “Laundry Money,” nailed the loaded water pistol to the top right corner of the painting where it remains to this day, along with traces of purple ink, as part of the now modified work which was acquired by the Centre Pompidou in 2004. So, when Banksy captured headlines a couple of weeks ago it was for deploying a strategy not so different from that utilized by Malcolm some 40 years earlier.

There are, of course, differences. In Morley’s case, the Parisian auction house, Palais Galliera, had been tipped off before the painting came up for sale on November 30, 1974, and it took measures to protect the painting. (That said, some people believe that Sotheby’s was aware of the Banksy stunt in advance, despite its repeated denials.) But there are also similarities, of a sort: like Banksy’s “new work” that resulted from the shredding, Morley’s piece seems to have gained value from its play-acted defacement, having eventually ended up in a prestigious museum. It came up for auction again in 2004, at Christie’s London, and was bought by the Centre Pompidou, the modern and contemporary art museum in Paris for GDP 341,250, about $650,000 at the time.

Images from the auction of Buckingham Palace with First Prize. Click to enlarge

COURTESY SPERONE WESTWATER

Here’s Morley describing the incident to interviewer David Ebony in 2011:

EBONY: Early on in your career, you became known for some provocative incidents, like when you attacked a painting of yours at an auction as it came up for sale.

MORLEY: That was at an auction in Paris. It was a painting of Buckingham Palace I did in 1970 that had been commissioned by the flower company F.T.D. [Buckingham Palace with First Prize]. There were a number of artists also commissioned, and I decided to give myself first prize, and stuck the ribbon in the corner. Around that time I was very taken in by Artaud and when the painting came up for auction a few years later, I developed a performance piece. I asked friends to come to the auction, and let them know that I was going to do this event and maybe shoot paint at the canvas with a water pistol. The auction house was tipped off about it and when the painting came out they had it covered in plastic. I was dressed in a tuxedo with long tails. I had hired a violin player. She started playing and I spouted off a speech I wrote about how God means the painting not to be a fake, or something like that. I went up to the painting and nailed the water pistol onto the canvas. The audience was beside itself, shouting and laughing, and the auctioneer stopped the sale. The painting was eventually bought by a Swedish collector, and now it’s in the Pompidou collection—with the water pistol still attached.

Malcolm Morley, Buckingham Palace with First Prize, 1970.

COURTESY SPERONE WESTWATER

According to Morley’s studio, not only did he attempt to spray the ink-filled water gun at the painting but he also handed out chocolates and planted people in the audience (shades of Banksy’s remote-control controller!) to stand up and shout “don’t be afraid.” He may even have used the auctioneer’s gavel to hammer the pistol to the painting.

One thing that can be said without question is that both artists have a sense of humor.

Writing for ARTnews in 2015, painter David Salle observed that before hitting a eureka moment in the early 1980s with his painting Cradle of Civilization with American Woman, Morley “had been working for years to find a way to translate his fracturing, shattering, and disjunctive impulses into paint. In Cradle the transgressive id runs riot; the picture is a gas.” In a review of Morley’s recent, posthumous exhibition at his longtime New York gallery Sperone Westwater, New Yorker critic Peter Schjeldahl characterized the artist as “fun though somewhat alarming company,” and stressed the need for a proper Morley retrospective in the U.S., writing, “I fancy one that would focus on the onsets of Morley’s stylistic convulsions . . . to emphasize the demonic restlessness of his sensibility.”

Here’s to the transgressive id, may all of ours outlive us.

[ad_2]

Source link