[ad_1]

This story was reported in partnership with Type Investigations.

DETROIT — It was here before we knew it was here.

It was on Maddelein Street on the morning of March 6, when the 9th Precinct on the east side hosted a “Police & Pancakes” breakfast. About 100 people showed up, pooling syrup on paper plates and small-talking with officers, including a 43-year-old community leader named Marlowe Stoudamire, broad-smiling and beloved, who would be dead in three weeks.

It was almost surely downtown that evening, at the sprawling convention center on the Detroit River where Sen. Bernie Sanders enticed thousands to rally ahead of Michigan’s presidential primary. And likely, too, at a high school on West Outer Drive on the eve of the primary, when 2,000 supporters of former Vice President Joe Biden showed up for another shoulder-to-shoulder rally, getting a shot of hand sanitizer on their palms as they passed through the door.

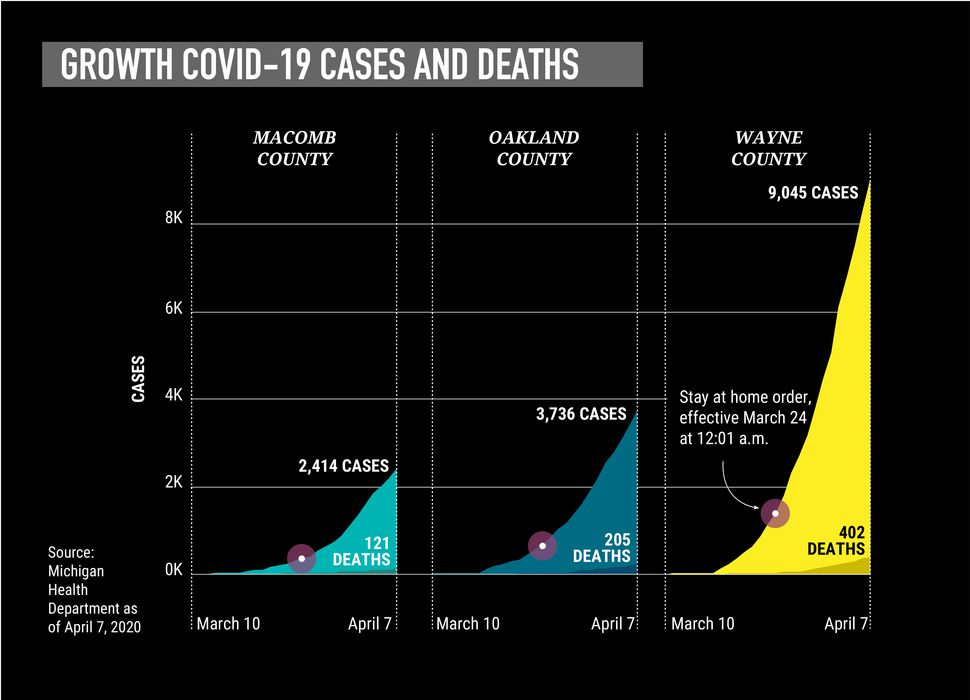

Biden won the March 10 primary, with historically high turnout. Three hours after the polls closed, Michigan’s governor stepped before the cameras, far more staid than she’d been at the Biden rally the night before. The coronavirus was here, she said. The first two cases were confirmed, both in the Detroit area. In scarcely a week’s time, the number of sick people multiplied 40 times over. Three died: one from Detroit, two from nearby suburbs.

The coronavirus was here, in one of the nation’s poorest and blackest big cities, a place where the incidences of asthma, diabetes and high blood pressure are all more than 50% above the national average. Proud of its history as a mobility hub, Detroit is also one of North America’s busiest land border crossings and home to an international airport where 1,100 planes pass through every day, including direct flights to Seattle, New York City, Rome, Seoul, Shanghai and Beijing.

This enduring city, just five years out from the largest municipal bankruptcy in U.S. history, is framed as a comeback town, ready for revival. But in a cruel twist, the coronavirus turned the city’s greatest strengths — its connectedness and its networks of mutual aid — into a deadly threat.

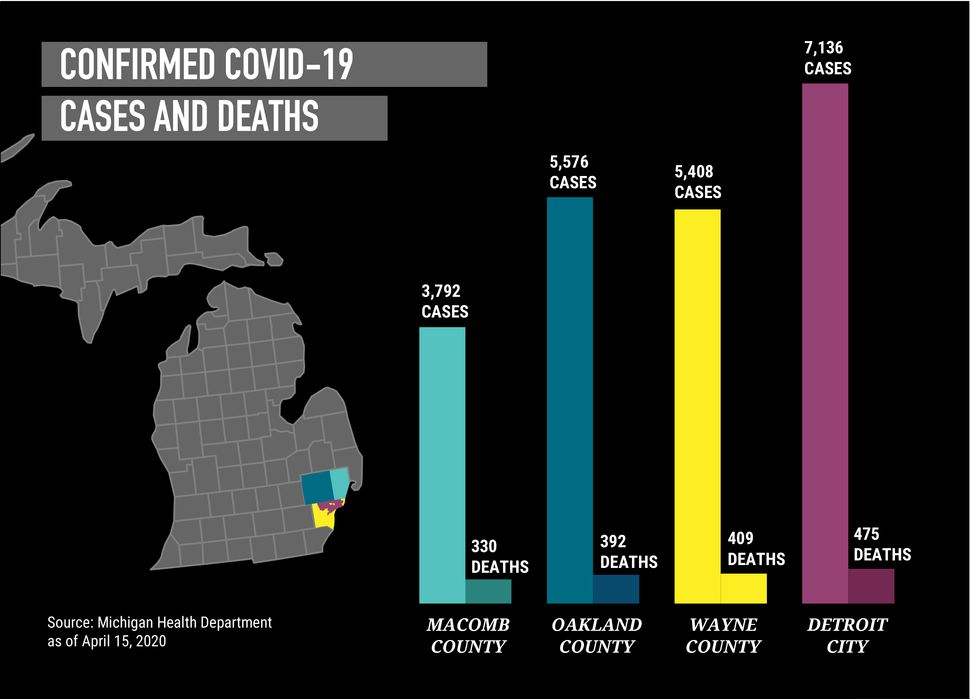

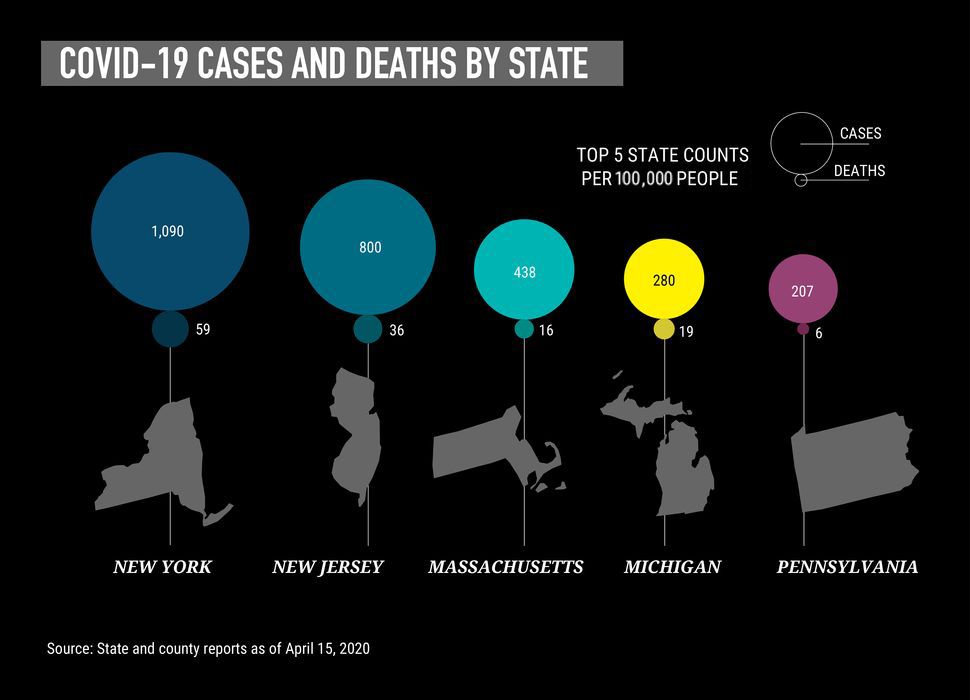

As of Wednesday, COVID-19 had infected more than 7,141 Detroiters and killed 469 of them. Michigan, which has reported 1,921 coronavirus deaths, has the country’s highest death rate. Of the statewide death count, 80% have been in the Detroit region. Wayne County, where Detroit sits, has more deaths than the state of California.

Over the past two weeks, HuffPost and Type Investigations have spoken with dozens of officials, health care workers and their patients, particularly at three of the city’s major hospital systems, Henry Ford, Beaumont and Detroit Medical Center, as they confront a novel pathogen while struggling with familiar hardships: a fragmented health care system, an underfunded safety net, and governments unprepared to deal with a crisis of this magnitude.

It was like going from nothing to being on the front line.

Chris Wasen, nurse

Many of the stories they tell — of supplies running short, of medical challenges unseen, of emotions rubbed raw — echo what workers and patients in cities like New York and New Orleans describe. And they are likely a preview of what’s coming to the rest of the country as the pandemic continues to spread.

The stories from metro Detroit’s big hospitals include tales of innovation, persistence and even triumph. In just the last week or so, a shift in admitting patterns suggests, however tentatively, that the number of new infections may have finally stopped rising.

But even if the worst turns out to be over for Detroit, COVID-19 has exacted a terrible toll here, measured not only in lives lost but also in lives changed.

‘We’re Going To Be Made The COVID Unit’

In early March, Chris Wasen was still caring for patients as they recovered from knee and hip replacements. As an orthopedic surgery nurse at Beaumont Hospital, a major medical center in metropolitan Detroit, he helps people escape pain they’ve lived with for years.

In an earlier life, he taught science to middle schoolers. His father had been a teacher; his mother a nurse. His girlfriend, also a nurse, works on the same floor as he does.

Then nonessential procedures were canceled on March 15. The next day, his girlfriend called from work: “We’re going to be made the COVID unit.”

A COVID-19 step-down unit, to be exact, with 114 beds for patients. “It took a little bit to sink in,” Wasen said. “It was like going from nothing to being on the front line.”

Detroit has wrestled with public health emergencies before. For decades, hospitals like Beaumont and the Henry Ford Health System have been holding drills to prepare for all kinds of disaster scenarios, including terrorist attacks, chemical spills and building collapses. And many health care providers also had plenty of practice with real-life pandemics: SARS in 2003, H1N1 in 2009 and Ebola in 2014.

But COVID-19 spreads like nothing else. It’s far less lethal than SARS or Ebola, but it has a long incubation period. Seemingly healthy people can spread it for days before showing a single symptom. Some never show symptoms at all. Evidence suggests that it can travel dozens of feet through coughs and sneezes, or even just by talking or breathing, and that it can live in the air for hours.

John Deledda, chair of emergency medicine at Henry Ford, first heard back in December that “something was not right in China.” He grew more worried as the World Health Organization sounded the alarm about a fast-spreading virus, and when the U.S. had its first confirmed case — a traveler from the Seattle area.

But it was in the middle of February, when he returned from a vacation in Florida to a bustling terminal at Detroit’s airport, that the scope of the crisis hit him. All these flights, from all over the country, from Asia and Europe. All these travelers, touching water fountains, ATM touch screens and escalator handrails.

After that, preparations got more intense, with the hospital stocking up on supplies, figuring out new personnel rotations and setting up a tent outside the emergency department for quickly isolating likely COVID-19 patients.

But when the patients started showing up in mid-March, slowly at first and then in a deluge, Deledda and colleagues quickly realized they’d need to change their protocols. The official guidance said to screen for cough and fever. But within a day, they realized some people without those symptoms also had the disease. “It was like, ‘Whoa, wait a minute.’ … You basically had to get to a point where you just have to assume everybody had COVID.”

Over at Beaumont, the transformation was just as acute. It took a couple of days to move patients from Wasen’s orthopedic clinic to other floors. Once emptied, it filled with COVID-19 patients in just an hour — people who were sick enough to need hospitalization but not so sick that they had to be in the intensive care unit.

Their conditions varied. One 90-year-old woman sent over from a nursing home had dementia. She didn’t have a fever, her heart rate was good, her blood pressure was good and her breathing was assisted by a liter of oxygen — not bad at all.

But others who seemed stable declined rapidly and were sent to the ICU. One man had a fever and legs so swollen he couldn’t walk. He developed sores from being in bed so much.

“You try to see a pattern, any rhyme or reason to it,” said Wasen. “But it doesn’t seem to exist. Some people start to feel better, then all of a sudden it just goes the other way.”

Wasen’s shifts are 12 hours long, three days a week. When he steps into the unit’s hallways each morning he finds a weird quiet. Recovering patients aren’t permitted to open their shut doors. No families mill about, chattering, asking questions, looking for a cup of coffee. No families, that is, except if someone is about to die. Even then, they are muffled by protective masks and gowns, and can only stay for 15 minutes.

That personal protective equipment, or PPE, is essential for limiting exposure to this virus. But the equipment is also cumbersome. As another COVID-19 nurse in Detroit described it, the gown is “basically like wearing a garbage bag. You’re sweating, it’s so hot. Your glasses are fogging up your face, or whatever eye protection you’re wearing. You have a full mask on. And these patients are so sick. It’s sad.”

Wasen’s colleagues are also quieter than usual. People who might have come up to chat keep a distance. Some friendly faces from ortho are deployed elsewhere or quarantined with virus symptoms, replaced by staff from other departments that are largely shut down: pediatrics, oncology, gynecology, physical therapy, endocrinology.

“They haven’t done bedside nursing in years,” he said. “You can tell by the look in their eyes.”

And yet, other staffers request to be sent to the COVID-19 floor. At least there they’ve got gowns and masks. When exposure could happen anywhere, it feels safer.

More and more of them have been sent to the front lines over the last month, as every hospital in the city has seen a surge of sick patients that could overwhelm capacity.

A System Already On The Brink

By late March, the emergency room at Sinai-Grace, part of the Detroit Medical Center, buckled under the soaring number of COVID-19 cases. The hospital is one of eight owned by the Dallas-based Tenet Healthcare system, and even before the pandemic, staff had raised concerns that DMC was bleeding resources — from budget cuts to a continuing staff exodus.

A deadly turn of events in early April appeared to rip the net wide open. The coronavirus had infiltrated nearby nursing homes, which in turn filled the hospital with an overwhelming number of critically ill elderly patients. The ER faced a litany of horrors. Workers didn’t have enough N95 respirator masks, face shields, gowns and other basic PPE, said Tinae’ Moore, an emergency room technician.

The hospital ran out of even basic supplies: bandages, saline, body bags. Patients died in its hallways, while bodies were placed in vacant rooms and stacked on top of each other in refrigerated trucks. Patients sat in soiled diapers. The emergency room was in “shambles,” Moore said. An official with DMC estimated that 60% of the nursing home patients brought to area hospitals the first week of April died.

“We have run out of rooms, beds, run out of staffing, equipment, personal protection resources — it’s insane, absolutely insane,” Moore said last week.

As a 40-year-old steward for the Service Employees International Union, Moore is acutely aware of how hospital conditions affect workers, and how that in turn affects patient care. All over metro Detroit — especially, it appears, at DMC hospitals — irregular supplies have undermined both.

Supplies have also become a critical issue in other hospitals. At Beaumont, nurses sent an open letter to executives demanding N95 masks and other basic equipment that they said hadn’t been adequately supplied. Staffers at DMC and at least one other hospital reported a scarcity of the drugs typically used to sedate ventilated patients.

A DMC nurse said they are trying to substitute other drugs. But “there’s a reason we don’t use them,” she said, requesting that her name not be used for fear of reprisal. Those drugs leave intubated patients awake enough to be agitated. “They keep fighting the ventilator so their oxygen levels drop sometimes, and they’re moving around a lot, so they have to be put in restraints,” lest they disconnect themselves.

“Logistically it’s really shitty,” the nurse added, “because you have to keep a really close eye on them, and as a human it’s really shitty because these people will probably die, and this is how they’re spending their last moments: poorly sedated and agitated and alone.”

We have run out of rooms, beds, run out of staffing, equipment, personal protection resources — it’s insane, absolutely insane.

Tinae’ Moore, emergency room technician

Ventilators have been a particular concern. The trouble is that this critical-care device is typically only used by a patient for a day or two, so it’s not necessary to have a huge stockpile — usually.

But with this disease, “those put on ventilators stay on for weeks, several days at a minimum,” said Ruthanne Sudderth, the top communications official with the Michigan Health & Hospital Association. “So even with the shortages, you see a surge because of the time people are on them, and that compounds the shortages.”

As hospitals began to run low on ventilators, Henry Ford leadership circulated a draft memo outlining guidelines for making life-and-death decisions that prioritized saving healthier patients. Officials there said it was an internal document outlining policies for a “worst-case scenario” that never materialized. At Sinai-Grace, doctors debated whether to offer the hospital’s 70 ventilators to those over 65 years old, said critical-care physician Lobelia Samavati. She and others strongly opposed any such policy.

“I came to medicine to take care of patients, and I don’t want to play God,” Samavati said. Sinai-Grace ultimately received 10 more ventilators and never put the policy in place, she said.

There are moral risks, but also physical ones. While health care workers would typically dispose of masks after treating each patient, there aren’t enough masks to do so right now at many hospitals. Forced to adapt, DMC infectious disease specialist Teena Chopra developed rules for folding reused masks and placing them in bags to prevent cross-contamination. DMC residents turned to GoFundMe to raise more than $32,000 to supply their emergency department with better masks and other PPE.

But many workers worry that limited supplies and high-exposure situations could lead to more doctors and nurses getting sick. COVID-19 symptoms had sidelined over 1,500 staffers in Beaumont’s system and 700 staffers at Henry Ford’s hospitals by April 5. At least four had died.

In the intensive care unit at Sinai-Grace, a team of seven doctors and residents who typically treat 18 to 30 patients at a time were now responsible for 40 to 50 patients.

DMC, which typically schedules seven to 10 emergency room techs per shift, was working with as few as two on some shifts, said Moore. To protest low staffing levels, nurses staged a brief work stoppage on April 6.

But Moore wasn’t able to join any demonstrations of discontent. She’d already gotten sick herself. She came down with a fever and cough in mid-March. When her symptoms didn’t subside, a doctor ordered her to quarantine for another two weeks. She remains off-duty until at least mid-April.

“My phone rings 24/7 and I’m still actively working from home advocating for members, fielding calls all day long, because no one else is listening or picking up the phone right now,” she said of her duties as a union steward. Moore instructs workers on what to do if they aren’t feeling well or if they feel like management is overstepping boundaries.

Each health care worker who is not adequately protected is at risk of getting sick. And every worker who gets sick is one less fighting the disease.

Even when they do show symptoms, providers still have a hard time getting tested. There just aren’t enough supplies. Workers are triaged according to priority levels set by the state. For those who can’t get a test, hospitals must assume the worst and quarantine anyway. One Henry Ford nurse practitioner was exposed to co-workers who tested positive, but couldn’t get tested because the ER didn’t have enough swabs. She was sent home for four days as a precaution.

DMC’s Samavati called the early-April onslaught “the most difficult and stressful” situation she’s faced in 20 years in the ICU.

“The emotional part is affecting health care workers, physicians, residents and fellows because of the anxiety and fear that you are going to acquire it, the anxiety that you are not able to do anything about it, the anxiety that you don’t have the right protective equipment,” she said. “A lot of people — they can’t cope with it.”

Yet the conditions are creating a sense of camaraderie among health care providers, said Chopra, the infectious disease specialist. “We are all humans and we feel different kinds of emotions including sadness and ‘Why me?’ But then I also think that this pandemic has brought everyone closer.”

At Henry Ford, the clinical psychology unit now treats its hospital colleagues with a hotline and three virtual group therapy sessions a day.

When a COVID-19 patient is discharged, Journey’s “Don’t Stop Believin’” plays on the loudspeaker. At Beaumont, it’s The Beatles’ “Here Comes the Sun” when someone comes off a ventilator.

“Yesterday, they played it five or six times,” Wasen said. “That was nice.”

‘Is This Over Yet?’

Wasen has trouble sleeping before his shifts at Beaumont’s converted COVID-19 unit. But he shows up and changes into scrubs and gets his mask for the day — one to last the full shift, one that has already been used and disinfected. After a morning huddle, he keeps watch on about three patients for the next 12 hours.

He checks often on patients with high fevers, and monitors everyone’s vital signs at least three times a day. Because it’s an ortho floor, there aren’t pulse oxygen monitors in each room, so they use incentive spirometers — hand-held devices with a breathing tube and air chamber — to clear lungs. At mealtimes, Wasen checks the sugar levels of diabetics and gives them insulin. He also talks by phone with family members who can’t visit and need an update. His colleagues have had tougher tasks, like setting up video chats for dying patients.

His unit has also been receiving more nursing home patients with complicating conditions.

“Some of them, the look in their eyes, if they are not verbal, you don’t know what’s going on in their head,” Wasen said. He can only hold their hand.

This kind of work has led to fatigue and incredible stress for health care workers.

“Every morning I wake up and I’m like, ‘Is this over yet?’ because we’re always thinking about how people are suffering,” said Asha Shajahan, a family practitioner at a Beaumont clinic in an inner-ring suburb.

Samavati said she and other physicians work nearly nonstop, sleeping only four hours a night between their shifts in the hospital and their research into treatment and cures for COVID-19.

“The physician goes into this profession to treat patients and cure disease, but we don’t have the cure right now,” Samavati said. “We feel like we can’t do anything about it, and that’s where there’s sometimes a sense that we’re losing.”

They are also working against the cascading set of conditions that made Detroit uniquely vulnerable in the first place.

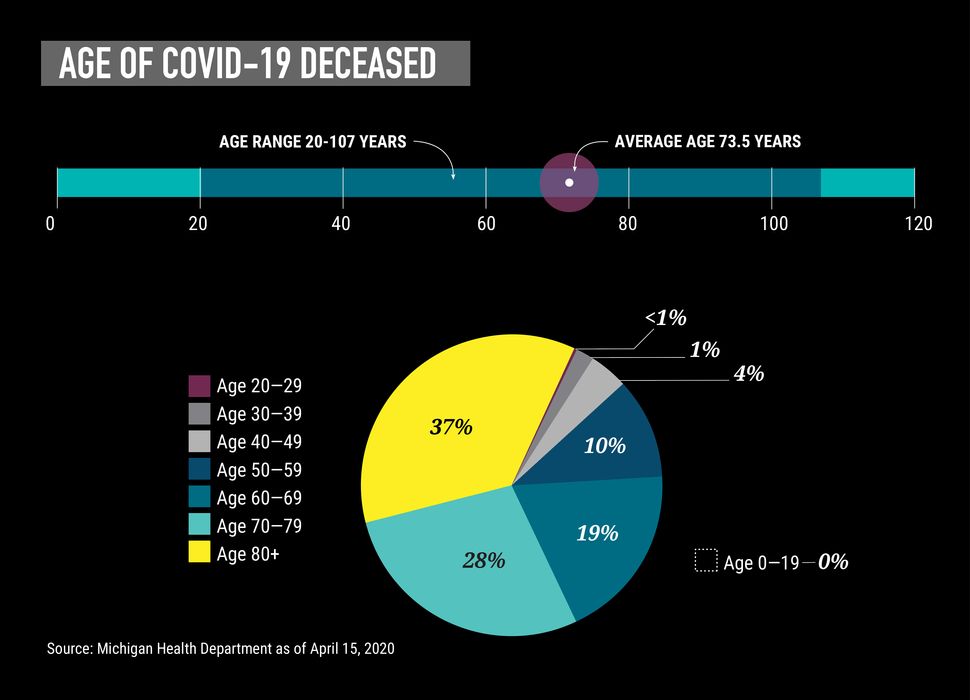

This is one of the most segregated regions in the country, where a separate-and-unequal system magnifies racial disparities. Research has found that city residents — 79% of whom are Black — live 16 years less than their suburban counterparts. The coronavirus amplifies a precarious pattern. Among those infected in the first weeks were prominent African American leaders: police chiefs and captains, a news anchor, a state representative. Even outside Detroit proper, Michigan’s Black communities are far harder hit than others. Nationally, available data shows that 42% of those who have died from COVID-19 were African American.

At the same time, more than one-third of Detroiters — about 224,000 people — live in poverty. This contributes to chronic health problems, like diabetes and hypertension, which in turn make people more susceptible to severe, potentially lethal complications from COVID-19. At a time when hand-washing is more important than ever, thousands of residents have endured water shut-offs.

A lack of access to health care exacerbates those conditions. With the help of the Affordable Care Act’s expansion of Medicaid, the number of people without insurance in Michigan has declined significantly, leading to more care, better health outcomes and more financial security for the state’s poorest residents. But even with that improvement, more than 30% of the city’s residents had trouble paying medical bills in the last 12 months, according to unpublished survey data that the Center for Health and Research Transformation, a think tank affiliated with the University of Michigan, analyzed for HuffPost and Type.

Vern Davis Anthony, a former Michigan, Detroit and Wayne County public health director, said these disparities “put us behind some of the underdeveloped countries.” The virus, she said, “could really rupture our health care delivery system. I think we’re going to learn there’s no us and them. We’re going to learn the hard way we’re all in this together.”

Compounding the problem is a relative lack of private providers, in part because it’s harder to make money when so many patients are on Medicaid, which pays less than commercial insurance. “A lot of folks, they don’t have a provider, somebody to talk to when they get sick,” said Abdul El-Sayed, an epidemiologist and Detroit’s former public health director. “That’s a real problem in a situation like this.”

I think we’re going to learn there’s no us and them. We’re going to learn the hard way we’re all in this together.

Vern Davis Anthony, former public health director

Air pollution, which research recently linked to a higher death rate from COVID-19, is another chronic challenge. The Motor City is in a sprawling, car-dominated metropolitan region, which contributes to respiratory diseases that can be debilitating and even lethal. It has also struggled with toxins from a now-closed incinerator and a refinery. In 2019, Detroit had the 10th most asthma-related deaths of any American city.

The possibility of very sick patients overwhelming Detroit’s health care infrastructure is one reason that Gretchen Whitmer, Michigan’s governor, has been heeding the advice of her scientific advisers. In March, after a series of steps gradually restricting public activity, she effectively shut down the state except for essential businesses. In just the last week, some Republican officials and their supporters have said the stay-at-home order is too restrictive; Whitmer says it is necessary to relieve the pressure on hospitals.

Whitmer, like most governors, had expected the federal government to play a key role in pandemic management by, among other things, tapping its emergency stockpile and using wartime production powers to guarantee an adequate supply of essential medical gear.

But even as President Donald Trump activated the federal response, he told governors both publicly and privately that they would have primary responsibility for obtaining supplies like ventilators and N95 masks. Whitmer was among the governors who questioned that decision, in part because of the panic her office was picking up from hospitals.

“In southeast Michigan, one hospital had what they thought was a year’s supply of PPE,” a senior Whitmer administration official said. “They burned through that in a week.”

‘I Felt Like I Was Being Strangled’

Chris Wasen met Chilah Harper on a Saturday shift at Beaumont’s converted COVID-19 unit. A 43-year-old mother and nurse who works at Detroit’s Veterans Affairs hospital, Harper was now in need of caregiving herself.

Harper had awoken on March 16 with what seemed like the flu. Terrible body aches. A fever of 103.

“My fingers were hurting,” she said. “My feet were hurting. My whole body was aching to the point it was paralyzing. I couldn’t get out of bed.”

She forced herself up the next day. Beaumont had just started drive-up testing for both the coronavirus and influenza. Harper got tested and was told to quarantine at home. Her negative flu results came a day later, but for COVID-19 results, she had to come in for a second test.

Before those results came in, she woke up with a crushing headache and shortness of breath. “I felt like I was being strangled.”

She woke her daughters, 11 and 20, to say goodbye and drove herself to Beaumont’s emergency room.

“They weren’t doing any valet, so I had to park my car and had to walk from my car to the hospital, which was such a struggle,” Harper said. “They met me with a wheelchair. They took me to the ER, which was virtually empty. I went to the back very quickly and that’s when they started the critical care.”

Stable, but struggling, she was sent to Wasen’s unit.

At one point, a respiratory team had to be called in the early-morning hours as she fought for air. Another episode happened in the late afternoon.

“It was just so hard for her to get a breath,” Wasen said.

Oxygen helped, but she struggled when doctors tried to wean her off of it.

“I was scared to go to sleep. I was scared to lay flat,” she said. She kept her bed at a 90-degree angle. “I kept thinking I was going to die in my sleep.”

By the time Wasen met her, “she was just zoned out. You didn’t know if she was hearing you talk or not,” he said. And yet, that same day, she got herself up to take a shower, which Wasen noted with hope.

By Sunday, Harper reported a terrific night’s sleep. Her oxygen levels improved. It was a chore to move, but she moved. On Tuesday, nine days after she’d been admitted, Harper went home in the cool spring afternoon.

Keeping The Numbers At Bay

One of the ways that Beaumont and others are managing the pandemic is by keeping as many people out of the hospital as they can.

That means leaning more on outpatient doctors in hopes of lessening the pressure — and the exposure — in emergency rooms.

Beaumont health system has been treating about two-thirds of its COVID-19 cases remotely, mostly via “video visits,” said Shajahan, the family practitioner.

Their success is a bright spot, she said. She looks for signs that the person on the other side of the screen should seek emergency care. But if they’re suffering mild symptoms, Shajahan instructs them to take Tylenol and drink fluids.

“A lot of people who are going for COVID testing are being sent home because they wouldn’t benefit from being in the hospital at this point,” Shajahan said. “They can manage their symptoms at home.”

Detroit’s Cabrini Clinic, a free clinic in the Corktown neighborhood skirting downtown, does an analog version of this. Some patients call the clinic from outside and a staffer simply delivers their medicine to them. “The main anxiety for them is, will we still supply them with their medicines?” said Alisa Smith, a nurse practitioner.

Outpatient doctors like Shajahan have been handling about 22 online appointments a day, nearly all confirmed or suspected COVID-19 cases. But even telehealth takes a toll. Blocks of video visits with COVID-19 patients require more energy than the usual flow of in-person appointments, which are often easy checkups, medication refills and routine vaccinations.

An outbreak is something different.

“It’s all a lot more emotional,” Shajahan said. “Every single case is someone who’s afraid of a life-threatening virus, so it takes a lot more patience and time.”

Both policymakers and providers have spent the last month looking for ways to rapidly expand capacity. Even in the midst of a now-infamous back-and-forth between Whitmer and Trump, the governor has worked with the Federal Emergency Management Agency, the state’s congressional delegation and local business leaders to find equipment wherever they can.

It helps that Michigan’s auto industry has deep connections to suppliers, especially in China, which is the world’s leading source of N95 masks. But the task is still daunting, in part because of the worldwide demand for supplies and the unruly market that developed as a result.

“If you’re not in the millions from an order standpoint, you’re also getting bumped on the ground in China,” a senior Whitmer official said.

Every single case is someone who’s afraid of a life-threatening virus, so it takes a lot more patience and time.

Asha Shajahan, family practitioner

Resourcefulness and charity are filling some gaps.

The state hospital association reached out to every private sector partner it could think of to get donated or purchased shipments, said Sudderth of the hospital association. In just one example, the utility company DTE Energy provided 100,000 KN95 masks. Ordinarily used for sewer work, they are roughly equivalent to N95s.

Detroit set up a drive-thru site on the state fairgrounds that could eventually test 1,000 people a day — albeit with a prescription — and it provided a $2 ride with home pickup for residents without transportation. Henry Ford figured out how to do its own COVID-19 testing early on, with results back in a day. After struggling with long waits for results, DMC is beginning rapid turnaround testing, with results in 24 hours.

Henry Ford also converted anesthesia machines to ventilators, said Steven Kalkanis, the Ford medical group’s chief executive officer. Donations from Tesla and the Ford Motor Co. also added to its vent supply, giving it a secure foundation.

With cheery colors and fanciful drawings, a whiteboard in the Beaumont lobby tracks discharges. Some go straight home, but still need to take precautions. Others are ready to leave the COVID-19 unit but linger because there is no place to send them, even though Beaumont and Henry Ford converted some of their facilities for recovering patients.

Beds are still a precious resource. By March 30, DMC was transferring patients to hospitals in Pontiac and Ann Arbor as it ran low on beds, said Chopra, the infectious disease specialist.

In perhaps the most significant example of multiplying the state’s capacity to heal its sick people, the TCF Center, the city’s riverfront convention center, opened on April 10 as a 1,000-bed field hospital that military medics and volunteers will staff. It was constructed in nine days in the same mammoth building that hosted the Bernie Sanders rally last month.

It is now lined with 350,000 square feet of curtained partitions marking off makeshift rooms that each have their own supply of supplementary oxygen, as well as staff changing areas, a command center and a pharmacy. Air filtration systems have been engineered to provide negative pressure and cleaner air. Seventeen patients were being treated there as of Wednesday.

All together, up to 3,900 new beds across the state were brought online in a matter of weeks, said Sudderth. “Hopefully this will be a pressure release valve that helps the situation in southeast Michigan.”

A Looming Financial Crisis

All this massively expanding capacity comes at a cost. Skyrocketing prices for large amounts of equipment and increased staffing, including overtime, have exploded hospital budgets.

That’s especially the case with the suspension of revenue-generating procedures — which many institutions did voluntarily, before the governor’s orders. Smaller hospitals are at risk of shutting down for good. Within the Henry Ford system, 8,000 procedures have been canceled since mid-March, said Kalkanis.

Beaumont this week reported a net loss of $278.4 million for the first quarter of 2020. Henry Ford and DMC have not yet reported their lost revenue from canceled procedures, but the financial hits are likely to be staggering: tens of thousands of dollars lost for every knee replacement, mastectomy, angioplasty and heart bypass surgery, plus thousands of lost walk-in and well visits and tests like mammograms.

“This whole pandemic has put great financial weight on the shoulders of all kinds of hospitals of all sizes, in all parts of the state,” Sudderth said.

Michigan set aside $50 million for COVID-19 health care needs, although the big money will have to come from Washington, because only the federal government has the resources and isn’t encumbered by balanced budget requirements. The CARES Act, which Congress passed and Trump signed in late March, allocated $100 billion for hospitals, and $30 billion of that is already on the way to individual institutions in the form of direct subsidies based on how much they billed Medicare last year. But it might take still more government money to keep hospitals, especially rural and safety net institutions, from going under.

“None of it can come fast enough,” Sudderth said. She hopes the funding will come with enough of a reserve to help hospitals through future emergencies.

Trinity Health announced that it will furlough 2,500 employees, or 10% of its staff, at eight hospitals across Michigan, including the Detroit suburbs. It is meant to make up for a 50%-60% loss in revenue since the crisis began, according to the announcement. Executive pay will also shrink. Over at DMC, an emergency nurse who works with COVID-19 patients learned by email that staffers are having their 401(k) contributions postponed. Some underpaid nurses have left for better contracts in New York.

Yet, for all this, there has been good news. Henry Ford had a milestone: As of last Friday, more people were weaned off ventilators than put on them. Word came a few days later that a second field hospital scheduled to open in a Detroit suburb had scaled back from 1,100 beds to about 250, and the University of Michigan health system put on hold its plans to convert an indoor track facility in Ann Arbor into a hospital, citing a COVID-19 curve that appears to be flattening.

At Sinai-Grace, doctors now have a handle on the influx of nursing home patients, Chopra said. She and a team led by the city of Detroit undertook a massive effort to test every patient in the city’s 26 nursing homes, and those with positive results are being isolated and treated.

Deledda, from Henry Ford’s emergency room, gives a lot of credit to the stay-at-home order, which he is convinced has slowed the spread around Detroit significantly. But, he said, it also helps that he and his colleagues have learned to treat patients more effectively — for example, by positioning them on their bellies, rather than their backs, in order to better oxygenate their lungs.

A physician colleague from Henry Ford’s West Bloomfield Hospital, Steven Rockoff, said the early use of steroids to reduce lung inflammation also seemed to help, even though early guidance out of China suggested the opposite. “We are learning as we go. … There’s no playbook on this yet,” Rockoff said, noting that Henry Ford has changed its treatment algorithms “probably four or five times already.”

The doctors are sharing these insights and comparing notes with counterparts all over the world. And at two hospitals, they are part of more formal efforts to improve COVID-19 treatment. Beaumont announced this week that it’s staging the nation’s largest study on COVID-19 antibodies to find out if people who get the virus can get it again, and how long it takes before it’s safe for people to return to public life.

I don’t think the system as a whole was well prepared for an international, worldwide pandemic.

Ruthanne Sudderth, Michigan Health & Hospital Association

Perhaps nothing would be more significant than finding an effective way to treat or prevent contraction of the coronavirus. And although most experts say it will be months and probably more than a year before a vaccine is widely available, Henry Ford is heading the first large-scale study in the U.S. on the use of an anti-malarial drug in preventing COVID-19.

Doctors already prescribe hydroxychloroquine as an off-label treatment for the sickest patients; this study will investigate its true effectiveness. In another Henry Ford study, researchers are looking at the antiviral remdesivir as treatment for adults with severe cases of COVID-19.

In announcing these studies, Henry Ford’s chief executive sounded a Churchillian note.

“Unfortunately, we’re now a hot spot in the United States,’’ Kalkanis said. “But Detroit has always been the comeback city. Detroit turned car factories into tank factories and won World War II. Detroit stands for resilience. Detroit will lead the country in our war against COVID-19.”

The work will continue, even on the other side of the crisis.

“We’re going to learn a lot about pandemic planning from this experience,” said Sudderth. “I don’t think the system as a whole was well prepared for an international, worldwide pandemic.”

Awaiting The Other Side Of The Curve

When Chris Wasen returns home from work, he comes in through the garage. He strips to his underwear, puts his clothes in a plastic bag, and uses a disinfectant wipe to open the door. His clothes go right in the laundry.

Then he takes a hot shower and tries to block out the day. “Most people feel they could shower forever and they’re never getting clean,” he said.

But anxiety is a live wire. Once he is away from the endless demands of the COVID-19 floor, the feelings flood him.

One day in early April, Wasen discharged five people. This was big news. He hadn’t discharged anyone the week before. It was a pretty good day, maybe even the beginning of a downslope on that deadly curve.

At the end of his shift, a nurse approached him. It was her first day in the unit, and a patient had called for help. His wife was in the ICU. They were about to take her off the ventilator.

“We set it up so we could wheel the patient up there to see his wife for 15 minutes to say goodbye before we brought him back,” Wasen said, his throat catching. “That’s how the day ended.”

He tried to remember that five people went home that day, feeling more themselves than they had in weeks. It was a good day.

But still, he said, “you just can’t imagine.”

A HuffPost Guide To Coronavirus

Calling all HuffPost superfans!

Sign up for membership to become a founding member and help shape HuffPost’s next chapter

[ad_2]

Source link