[ad_1]

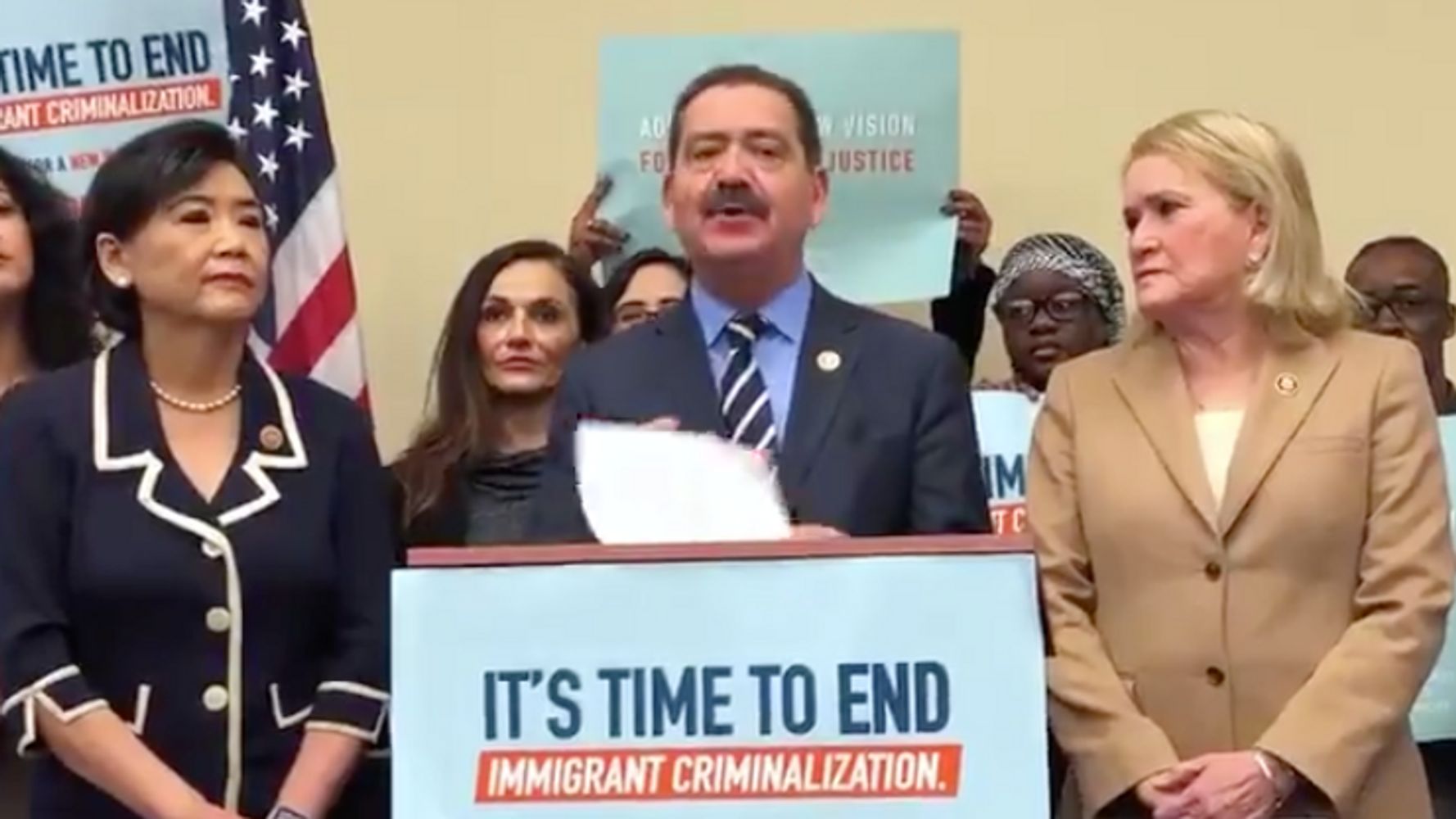

Democratic lawmakers announced broad legislation on Tuesday aiming to decriminalize migration and disrupt the “prison-to-deportation” pipeline.

The ”New Way Forward Act” from Rep. Jesús “Chuy” García (D-Ill.) ― co-sponsored by Reps. Ayanna Pressley (D-Mass.), Pramila Jayapal (D-Wash.), Karen Bass (D-Calif.) and dozens more ― aims to “correct racial and anti-immigrant injustices embedded in our immigration laws,” per a release from García’s team.

The package includes a slew of proposed legislation to overhaul the immigration system, including ending mandatory immigration detention, generally blocking local police from engaging in immigration enforcement and decriminalizing border crossings.

It would also seek to disrupt laws that broadly make involvement in the criminal justice system a threat to immigrants’ status in the U.S. ― namely by ending automatic deportation proceedings for people who’ve had certain convictions or other contact with the criminal legal system.

“We must end the labels of the ‘good’ versus ‘bad’ immigrant used to dehumanize and divide communities,” García said in the release. “An attack on one community is an affront to us all.”

“It’s time to end the criminalization of immigration,” reads the release.

The new legislation would decriminalize border crossings, a contentious issue among Democrats in recent years. It would repeal sections 1325 and 1326 of U.S. federal immigration law code, which make it a criminal, not civil, offense for someone to enter the U.S. outside official ports of entry or reenter after being deported.

Under the guise of section 1325 of the U.S. code, President Donald Trump’s administration notoriously separated thousands of migrant children from their parents at the border in 2018.

Following 2020 Democratic presidential hopeful Julián Castro’s repeated calls to decriminalize border-crossing, other leading Democratic presidential candidates have since publicly backed such a proposal.

The new package also attempts to undo some of the 1996 Clinton-era laws that added more severe punishment for immigrants who violate U.S. immigration or other criminal laws.

The 1996 laws notably removed much of judges’ discretion in immigration proceedings for people with previous criminal convictions ― for instance, green card holders (or permanent residents) are subject to mandatory deportation for many convictions that occur within seven years of their being in the U.S.

The new legislation would allow immigration judges to exercise discretion in cases, for instance, on humanitarian grounds. It would also stop “summary” or automatic removal procedures for immigrants based on prior criminal convictions, ensuring them a shot at a fair day in court.

An explainer on the new proposals points to how immigration reform is connected to racial and criminal justice issues. Law enforcement practices like stop-and-frisk and traffic stops have been shown to disproportionately target people of color.

“Convictions, often steeped in racial profiling, should not lead to deportation,” the explainer reads.

The explainer details the case of Howard Bailey, who came to the U.S. from Jamaica at age 17 as a lawful permanent resident with his mom, a U.S. citizen. After serving in the Navy, he was later convicted of a first-time drug offense in 1995 and pleaded guilty on the advice of his lawyer. A decade later, as a father of two who had started two small businesses, Bailey applied to become a U.S. citizen. In 2010, his application was denied and Immigration and Customs Enforcement came to his home and detained him. He was eventually deported to Jamaica, a country he hadn’t been to in 24 years, and remains there to this day.

The proposed legislation would create a statute of limitations for removals based on past behavior ― meaning the government could not start deportation proceedings based on criminal conduct that made someone “removable” more than five years earlier.

It would also limit ICE’s power to detain immigrants for the duration of their deportation proceedings by adopting “presumption of liberty” for all immigrants, as well as by requiring the government to establish probable cause within 48 hours of a person’s detention and ensure they have a bond hearing.

The legislation would notably block local law enforcement from broadly partnering with ICE in its enforcement of federal immigration laws, including having to share information on detainees.

And under the new legislation, people previously ordered deported, like Bailey, would be able to apply to return to the U.S. ― if they can show they would not have been deported under the terms of the new laws.

Calling all HuffPost superfans!

Sign up for membership to become a founding member and help shape HuffPost’s next chapter

[ad_2]

Source link