[ad_1]

My grandfather died on Christmas Eve. I never knew him, but his legend still hangs over me. Even though I’m named after him I’ve never visited his grave. I don’t even know where it is. All I know is that every holiday season my father will drink a little more and talk a little less. Sometimes he tells the story of my grandfather and his struggles. Mostly, he just mourns. Growing up to this rhythm I learned to fear death and push its pain down deep.

Consequently, death and loss have always haunted me. They stalk my every turn. When I was fifteen years old, my friend Jimbo Roche was murdered in Long Beach, California. We were supposed to be playing basketball together. Instead he got shot at the Burger King and crawled into the women’s restroom to die. Other friends would soon follow—all on different corners but in similar spots. I went to Jimbo’s funeral but, once again, I never visited his grave. I’ve never visited anyone’s grave. I wouldn’t know where to begin. I wouldn’t know what to say.

After a week in Lawrence County, Mississippi, however, I might be closer to that beginning. I might be ready to confront death. Why Lawrence County? It’s where the University of Chicago began. Ever since my colleagues and I at the Reparations at UChicago Working Group published our findings on the university’s ties to slavery we knew we had to see the plantation and the community that started it all. Our mission was simple: meet with the community and see if we could facilitate a future dialog of healing and reconciliation between the university and the descendants of enslaved people in Lawrence County.

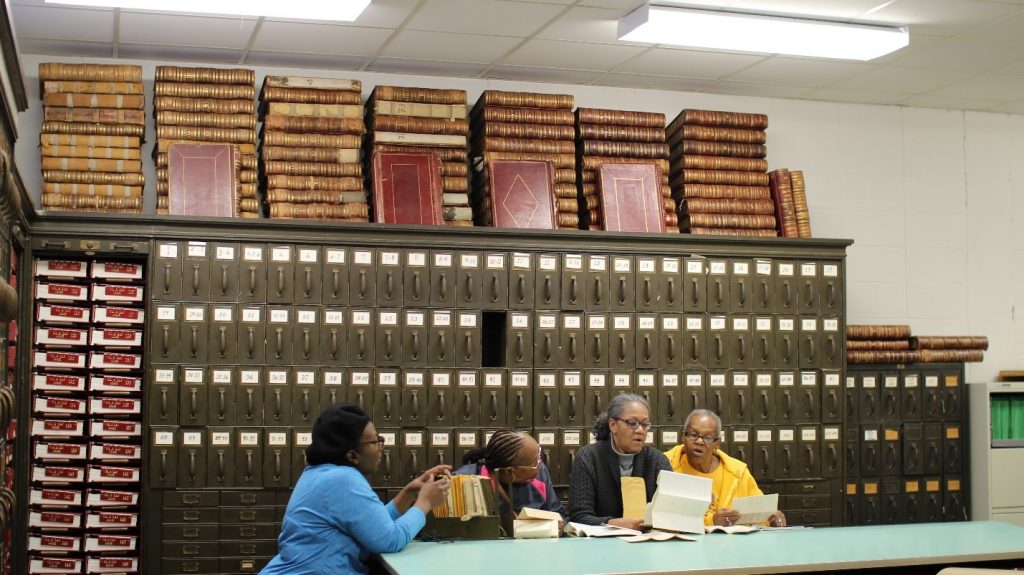

History is thick and heavy in Mississippi. I thought I knew this yet, unsurprisingly, the amazing Black women who led our way knew better. Sherry Williams, Nettie Nesbary, Lettie Sabbs, and Angela McGhee all live on the South Side of Chicago, but their spirits abide in Mississippi. As genealogists and preservationists, they are at home in Southern cemeteries communing with the ancestors. Court records, census rolls, and tombstones all seem to bend to their every command. “We can find a flea on the back of a dog’s a**,” they assure me. After a week with them, I believe it. As a historian, I usually end up fighting with the archives. While I struggle to read the silences these ladies know the silences, yet their certitude never lapses into naiveté. Their skepticism shouts when it should but vanishes when it must. And most of all, they simply love Black people.

A group of young Black men followed their female elders down South. For myself, Dr. Obari Cartman, his brother Ayinde Cartman, and my co-author at the Reparations at UChicago Working Group, Caine Jordan, this was our first time in Mississippi. Obari and Ayinde brought drums. They also brought a profound expertise in Afro-centric psychology, reparative justice, and Pan-African activism. Caine brought his usual thoughtfulness as a Black socialist. Then he ate two lunches back-to-back. Let the dozens commence.

Between our banter we were compelled to flip through “chattel records” looking for the enslaved Africans who made the University of Chicago possible. Our real destination, however, was the China Lee Missionary Baptist Church. The archives only confirmed what we had already suspected. The congregation was founded during slavery by the enslaved people on the Stephen A. Douglas plantation. It’s known today by church members as the Strickland plantation after Douglas’s overseer, whose name continues to pepper the archives. The church sits on the site of what was once a vast 3000-acre cotton plantation with over 123 enslaved people. This story was not new for the residents of Lawrence County but its connection to the University of Chicago was. In addition to a Lost Cause Civil War exhibit (that one would expect in any Southern museum) a larger-than-life rendering of Senator Douglas greets museum visitors in Lawrence County. He is well known as one of the area’s most prominent slaveholders.

To understand the living we had to begin with the dead. While the church maintained a well-kept cemetery dating back to the late nineteenth century, oral histories held that numerous older, unmarked cemeteries also dotted the area. One in particular contained the ancestral bones of the county’s only Black member of the Board of Supervisors, “Coach” Archie Ross. Members of the church remembered the day it was bulldozed over to make way for a new agribusiness—dumping their ancestor’s tombstones and corpses into the nearby creek. Enslaved bodies discarded in death just as they were plundered in life. Church members have to drive over that creek every day.

The church is still the center of the community. Sunday service is the center of that center. But our contingent was not the only presence from the South Side of Chicago at church that day. Barack Obama and his family fanned the worshipers. Hand-held cut-outs of the first family found use even in the snow-covered Mississippi winter. Here the breezes of Black excellence bathe the congregation and a stubborn yearning for hope still hangs in the air. What the congregation might not have known until our visit, however, was that even as they fanned themselves with the First Family, the Obama Foundation had struck a deal with the University of Chicago. In one of the many great ironies of the Obama legacy, the most famous community organizer on the South Side of Chicago was refusing to sign an agreement with community organizers on the South Side of Chicago. At stake is a Community Benefits Agreement to guarantee that the jobs, resources, and wealth that the Obama Library promises will reach the most disadvantaged members of the community. The call is for Obama to avoid future harm rather than contribute to its continuity.

Fittingly, the sermon was from Exodus 19:4-6. The descendants of America’s “peculiar institution” reflected on what it meant to emerge on the other side as a “peculiar treasure.” Reverend Jerry Earl interpreted slavery as divine providence—a blessing in disguise that strengthened Black people in the Lord. He further debated with our delegation about the presence of a white Jesus in his church using a sophisticated logic that mirrored Edward Blum and Paul Harvey’s findings in The Color of Christ. On at least three occasions, between the beautiful cries of the choir, mass incarceration came up during the service. Far from just a problem in the Black urban North, rural Mississippi has not escaped its claws. We just as easily could have been in Bronzeville. The warmth of the congregation meant we were at home.

In oral histories we collected from the congregation, the memories of sharecropping were immediate. The days of slavery were not yet lost. Our remarkable guide to China Lee, Rosetta Williams, told us about how her mother would sew used flour sacks into underwear for her as a child. Charlie Stewart told of his enslaved great-grandfather who fled the area after sleeping with the master’s wife. Pastor Earl’s ninety-one-year-old father revealed for the first time that while “working on thirds” he used to sell his cotton to the father of our generous white host in Jackson, Bo Bourne. Having known the elder Earl his whole life, but unaware of this connection, Bourne was left to tear up at the gravity of it all.

As we began to talk about how the University of Chicago might repair relationships in Lawrence County white Southerners were strikingly in league with their Black neighbors. Members of China Lee expressed a need for a community center, after-school tutoring for their children, and start-up funds for an organic co-op farm. The congregation would once again work the notoriously fertile soil of their ancestors—this time for themselves. The incredibly accommodating white mayor of the county seat at Monticello, Martha Watts, had already gone to bat with her board to secure government jobs for formerly incarcerated Black youth in the area. She came out in favor of opening a Black history wing of the Lawrence County History Museum as well as starting a job training program for young Black residents. The University of Chicago should help.

Reparations, in part, are about acknowledging the lives of the dead and how they continue to bear down upon the living. History itself can be viewed as the study of buried narratives and their resurrection in the service of the present. Historical causality demands, at the very least, that the actions of so many yesterdays be seen as the facilitators of tomorrow. Reparations, both material and symbolic, thus signal an intellectual maturity and a deeply held morality rooted in a commitment to justice.

Odd as it may seem, I’d never understood history as the study of the dead before. To me, my subjects were always alive. While I still admit to fearing death, at least I’m now ready to accept its life-giving possibilities. The ancestors spoke to us all in Lawrence County. We must now make the University of Chicago hear them as well.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.

[ad_2]

Source link