[ad_1]

Deana Lawson and Torkwase Dyson.

COURTESY BROOKLYN ACADEMY OF MUSIC

On a chilly evening last week, a crowd filled the sold-out theater at the Brooklyn Academy of Music. The occasion was a talk between artists Deana Lawson and Torkwase Dyson, a launch event for the recently published book Deana Lawson: An Aperture Monograph, which includes a sampling of 40 works by Lawson, an essay by Zadie Smith (which appeared earlier this year in the New Yorker), and a Q&A between Lawson and artist and filmmaker Arthur Jafa. The excitement in the air was palpable. This has, after all, been quite a year for Lawson, whose work has been gradually gathering acclaim. The fever pitch may have come last month, when she photographed Rihanna for the cover of Garage magazine.

Deana Lawson, Mama Goma, 2014.

©DEANA LAWSON; FROM DEANA LAWSON: AN APERTURE MONOGRAPH (APERTURE, 2018); COURTESY RHONA HOFFMAN GALLERY, CHICAGO AND SIKKEMA JENKINS & CO., NEW YORK

Lawson, donning a silver-sequined short-sleeve shirt, began by talking about her earliest experiences with photography. She pulled up some family photos, which she projected behind her and Dyson, and began discussing their influence on her. These were her bread and butter growing up. Seeing her father’s picture of her twin sister Dana pointed Lawson toward “the beginning of identifying with another person,” she said, “or trying to understand another human being’s pain, in a way, through looking at myself.”

She continued, “This connection between photography and seeing and sight and certainly subconscious, visual information, [was] registering to me on an emotional level, even though I [couldn’t] really formulate it early on.”

When she was an art-school student, Lawson was exposed to the works of a number of important photographers, including Jamel Shabazz, who captured the life and looks of young black girls, many of whom dressed, accessorized, and wore their hair like Lawson—”twinning,” as the photographer put it. Shabazz also shot black boys posing and showing off jewelry and clothing, and Lawson said he was able to capture their “coolness or swag” and their “masculinity.”

Dyson then launched into a discussion of the role authorship plays in Lawson’s work. Though not immediately obvious to most viewers, Lawson carefully stages each of her photoshoots of black men and women, and for Dyson, this adds layers of fiction to her work. “Texture [is] revealed through the camera itself, but also, quotidian moments end up being almost surreal,” Dyson said.

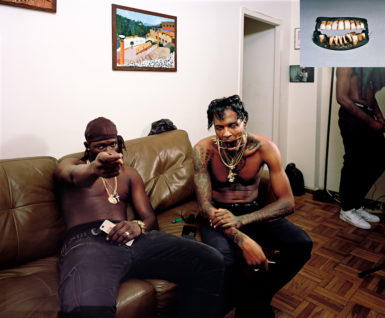

Deana Lawson, Nation, 2018.

©DEANA LAWSON; FROM DEANA LAWSON: AN APERTURE MONOGRAPH (APERTURE, 2018); COURTESY RHONA HOFFMAN GALLERY, CHICAGO AND SIKKEMA JENKINS & CO., NEW YORK

Lawson has an eye for detail—a clothing pile purposely left splayed about, for example, or a few plastic curlers placed in a subject’s hair. Dyson said that Lawson uses her camera to draw out these elements in the same way that a painter might rely on a brush to point out various objects in a scene. (One reason for this is Lawson’s cameras, a 4×5 or a Pentax 6/7, both of which are “not sexy,” due to their bulkiness, Lawson affirmed with a laugh.) And because of this, Lawson is able to capture the experience of the locations for her photographs, which have included the United States, Haiti, Jamaica, Ghana, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and elsewhere. Within each photograph, Dyson identified a dual world that marginalized people recognize—and identify with—as “thick with space, layered with otherness and belonging at the same time.”

Dyson and Lawson began pulling up individual pictures and discussing each one in-depth. One was 2018’s Nation, which features two shirtless black men on a brown leather couch. Lawson explained that Ruben, the man on the right, was late to the shoot because he was getting his hair’s “candy curls” done. The artist, who has often been attracted to gold as a symbol of the regal history of black and African culture, wound up spray-painting a mouthpiece gold in keeping with this idea, and had Ruben wear it for the photo. “I had a dream about this mouthpiece,” she said. “I found one on Amazon, and once it arrived, I spray-painted it gold because I wanted it to blend in with bling or with jewelry.” To her surprise, he had no qualms about putting it in his mouth.

Much time was spent on Lawson’s 2014 photograph Mama Goma, which shows a young Congolese woman wearing an electric-blue strapless satin dress with detached sleeves, her feet spread slightly apart and her hands held out in front of her, palms facing the ceiling. The woman is pregnant, and her stomach pokes through a hole in her dress, which was sewn to fit the woman’s body by a seamstress in Kinshasa. “I wanted to highlight the sacredness of carrying a child, and then months after this image was made, I would become pregnant with my own child,” Lawson said. “It’s interesting how pictures beget life.”

The woman’s ponytail became a sticking point for Lawson, who held her finger up to a laptop with the picture on it. “I was trying to see what this would be like without the ponytail,” she explained. “The ponytail is really the punctum. Because it brings me back to being a ten-year-old.” She seemed to be slowly drifting into a reverie about the past. “A wild ponytail,” she said, and then after a long pause: “Unruly.”

[ad_2]

Source link