[ad_1]

Roy DeCarava’s Graduation, 1949.

©THE ESTATE OF ROY DECARAVA AND DAVID ZWIRNER

David Zwirner has taken on worldwide representation for the estate of photographer Roy DeCarava, whose moody and diffuse black-and-white images tell bountiful stories of life in New York beginning in the 1940s and up through the decades before the artist’s death in 2009, at the age of 89. This fall, David Zwirner Books will help distribute a reissue of The Sweet Flypaper of Life, a 1955 book of photos and text that DeCarava made in collaboration with the poet Langston Hughes, and next year the gallery will stage a show of DeCarava’s work in New York around the occasion of the centennial of his birth.

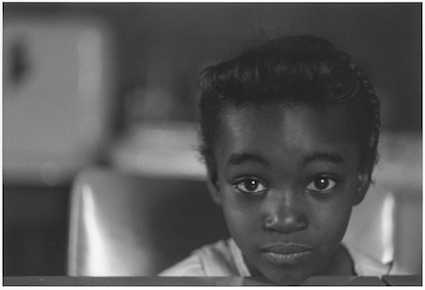

Roy DeCarava’s Arnette, 1953.

©THE ESTATE OF ROY DECARAVA AND DAVID ZWIRNER

Zwirner said his relationship with DeCarava’s oeuvre began last year after a revelation in England. “I was in London and went to Tate to see ‘Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power,’ ” a traveling exhibition recently closed at the Crystal Bridges of American Art in Bentonville, Arkansas, that opens this fall at the Brooklyn Museum. “A lot of the artists I knew, but then I walked into a small gallery where I saw all this black-and-white photography, and I was floored by the power of Roy’s images. I couldn’t believe I didn’t know the work, so I went on an investigation,” he said.

His curiosity led to Sherry Turner DeCarava—Roy’s wife and longtime collaborator who had been working to maintain his legacy—as well as artists for whom DeCarava is a touchstone. “The world of renowned African-American photographers is relatively small when you look at the ’50, ’60s, and ’70s, and Roy’s career is a classic case,” Zwirner said. “It was tougher for African-American artists to be heard in those years than it is today, and that’s one of the reasons we don’t know the work more. If you talk to people in the black community, he is really a benchmark of art-making in the 20th century. He’s a giant to those who know the work, and I think he’ll be a real discovery for those, like myself, who didn’t know.”

Roy DeCarava’s Coltrane #24, 1963.

©THE ESTATE OF ROY DECARAVA AND DAVID ZWIRNER

Among the DeCarava fans Zwirner cited are Kerry James Marshall, who’s on his gallery’s roster; Thelma Golden, the director of the Studio Museum in Harlem; and Kahlil Joseph, who paid tribute to the photographer in his film Fly Paper, shown at the New Museum last fall.

Asked how DeCarava fits into the whole of his program, Zwirner said, “I don’t think of photographers as photographers—I think of them as artists. What we need to do as a gallery is bring together the most unique voices in the visual arts, no matter what the medium and no matter when they worked. When I came across Roy’s work, I felt I was seeing a singular voice with a unique vision, and I thought I would like to be associated with that. We’ll see how the larger audience will react, but my feeling is that he really is a missing link.”

Poised and poignant depictions of black life in his neighborhood of Harlem and beyond were integral to DeCarava’s work. “One of the things that got to me,” the artist once told the New York Times, “was that I felt that black people were not being portrayed in a serious and in an artistic way.” Among his many subjects were figures engaged in a practice for which Zwirner has expressed deep appreciation in the past: jazz.

“That was the clincher,” Zwirner said of DeCarava’s storied photography of musicians at work and at play. “One of the images at the Tate was a photo of Ornette Coleman, which blew my mind. I didn’t realize how significant his photography of jazz is until I saw his book The Sound I Saw, a collection of his images around jazz. They’re not just superstars but musicians playing on the streets and in little clubs. When I saw those, I was even more convinced I wanted to be involved—that’s my personal passion.”

[ad_2]

Source link