Photo: Alun Callender

It all began in 2017, when a charity shop in Swansea put a notice in its window imploring people to stop donating copies of Dan Brown’s The Da Vinci Code. On average, the shop was receiving one copy per day. The plea went viral, catching the eye of the British artist David Shrigley, who decided to try and collect as many copies as he could, amassing 6,000 books over six years.

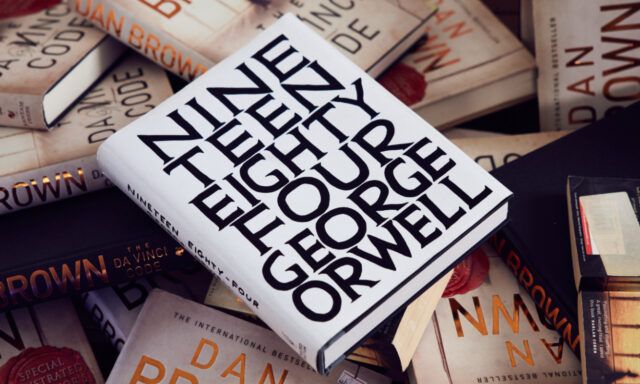

The brainwave to pulp them and turn them into copies of George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four came when Shrigley re-read the dystopian novel during the Covid-19 lockdowns—2020 marked 70 years since Orwell died, meaning the book was out of copyright and could be published by anyone.

This weekend, copies of Shrigley's limited-edition version of Orwell’s classic, Pulped Fiction, are on show in the Oxfam bookshop that inspired the project. Displayed in rows around the entire shop, the black-and-white covers have a dizzying effect on the eyes. “It reminds you of a totalitarian regime where there is no choice," Shrigley quips. "This is the book, and you’re going to read it."

The artist first read Nineteen Eighty-Four when he was an art student in the 1980s. On reading it again, he says he realised “that it was still a really resonant book, that it seemed even more relevant than when I first read it when you were invited to see it as a parable of Soviet or Chinese communism”.

Reading it in today’s climate, Shrigley sees the “subversion of language” in the book as more revealing of society, particularly when it comes to the words employed around war. “Ethnic cleansing is now the name for what used to be called genocide,” he says. “Russia’s invasion of Ukraine wasn’t a conflict; it was war. Conversely, it’s not a culture war. It wasn’t a war between Betamax and VHS, and it wasn’t a war between Blur and Oasis. Those were arguments.”

Shrigley remembers that the writer Margaret Atwood, when her 1985 novel The Handmaid’s Tale was made into a TV series in 2017, said something about how “there wasn’t anything in the book that hadn’t already happened in the United States, from the removal of women’s rights to the removal of civil rights from the general population. These weren’t invented phenomena. They were things that were actually happening at the time.”

The artist thinks the same could be said of Nineteen Eighty-Four. “War is presented as peace. Enemies are invented for us. We’re invited to think that black is white, and white is black. Day is night, and night is day,” he says. “It struck me that this is a book that people should read. It’s still really relevant.”

Though his project is not intended as “a piece of library criticism”, Shrigley describes The Da Vinci Code as “a holiday book about a fairly benign conspiracy—unless you happen to be a Christian and are quite offended by it, which is fair enough”. But, he adds, “it’s not the same level of conspiracy as QAnon, which does actually affect our politics in quite a direct and negative way”.

Does he think Brown would approve of his project? “He’s a difficult man to get hold of,” Shrigley says. “We’ve heard from his publicist, and there’s been nothing negative. There’s been no cease-and-desist.”

A collaborative effort between Shrigley and his studio team—which has worked tirelessly to source copies of The Da Vinci Code and track down the only paper mill in the country that would pulp still-inked paper—and others, including the graphic designer Fraser Muggeridge, Pulped Fiction is arguably Shrigley’s most conceptual work to date. (In a bizarre twist, Muggeridge’s grandfather, the journalist and broadcaster Malcolm Muggeridge, proofread the original novel for Orwell.)

Costing “well into six figures”, the project has been self-funded, and Shrigley says he may not make his money back. In Swansea, the newly printed books are selling for £495 for the first 250 customers, while the remaining thousand will be sold for £795 on Shrigley’s website.

“I’m in a position in my life now where I can actually afford to take risks and do things that I want to do, even though they don't necessarily really fit in my canon of work,” Shrigley says. “The really interesting thing about a work like this is that the conversation informs the work. It’s the conversations that you have which further its progress.”