[ad_1]

David Lynch, I was a Teenage Insect, 2018, mixed media painting.

ROBERT WEDEMEYER/COURTESY THE ARTIST AND KAYNE GRIFFIN CORCORAN

In the late 1980s, actress Isabella Rossellini brought the New York gallerist Leo Castelli to David Lynch’s painting studio in Los Angeles. About their first encounter, Castelli, a shrewd dealer known for his discerning eye, said at the time, “This man knows what he’s doing.”

Lynch had been making paintings, many of them depicting his nightmarish version of American suburbia, for two decades, though he was known then entirely for his films, among them the 1977 cult favorite Eraserhead and the 1986 absurdist murder mystery Blue Velvet. When Castelli gave Lynch a solo show at his SoHo gallery in 1989, the rest of the New York art world took its first look at the by-then-notable filmmaker’s paintings—though with reactions that split. One critic writing for Artforum called the show “eye-opening,” while Roberta Smith, in the New York Times, called the paintings “familiar, unoriginal, and slick.”

Decades later, it continues to strike some as a surprise that Lynch, an Academy Award–nominated director whose status is secure in Hollywood lore, has another significant practice devoted to painting, sculpture, printmaking, drawing, photography, and more—so much so that a 2012 essay about his studio work in Hyperallergic took the title “David Lynch’s Art Doesn’t Suck.” But the art world has gradually warmed to Lynch. His paintings were the subject of a retrospective at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Art—his alma mater—in 2014. A feature-length documentary about his art practice, David Lynch: The Art Life, followed in 2016. And this season, ahead of an exhibition opening in November at the Bonnefantenmuseum in Maastricht, Holland, Lynch’s art is on show at Los Angeles’s Kayne Griffin Corcoran gallery, which has represented him since 2011. The exhibition, which showcases paintings, watercolors, and drawings under the title “I Was a Teenage Insect,” opens September 8 and runs into November.

So how does Lynch himself feel about his work getting such visibility at long last? “It’s OK!” he said, speaking by phone from his office in L.A. “But it’s just been recently OK, because they don’t really take painters seriously if you’re known for something else. You’re supposed to only do one thing, right? But now things have changed.”

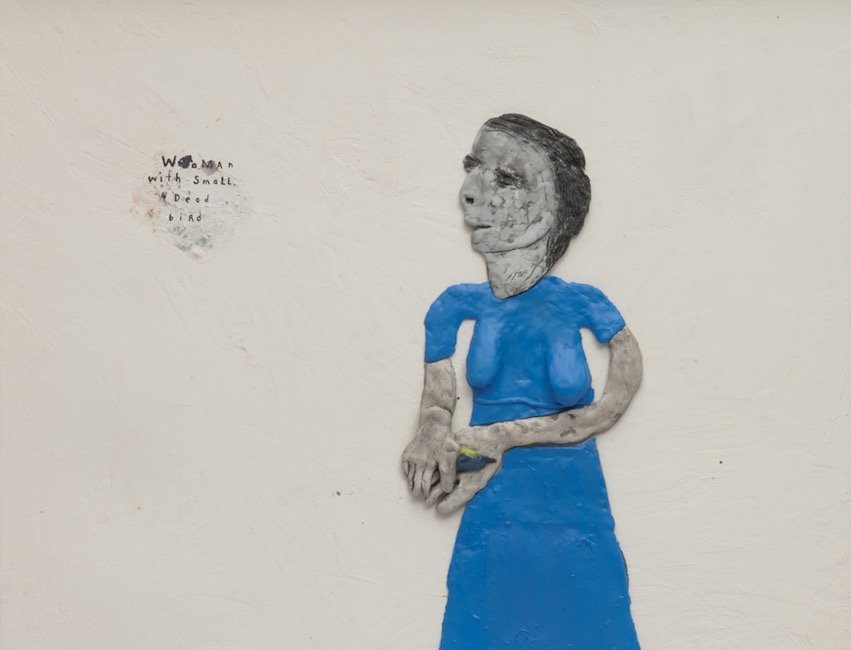

David Lynch, Woman with Small Dead Bird, 2018, mixed media painting.

ROBERT WEDEMEYER/COURTESY THE ARTIST AND KAYNE GRIFFIN CORCORAN

Lynch’s paintings are logical counterparts to his films, with subject matter that is, to put it mildly, quite weird. The works in the new gallery show feature, among other things, an insect-person by a small house, a woman floating in the ether, a man gazing at a potato, and a person being chased by some nondescript evil force down a hallway. Lynch, who has often said he doesn’t consider himself all that strange, is content to keep his art mysterious, speaking in oneiric statements that may or may not hint at what’s happening in the work.

Text, in some cases, helps viewers along. The painting titled Big Sheep Did Eat My Brain (2018) features a note, scrawled in inky paint, reading “I have been here before. When?” With such words in the midst of a drawing of a clock, it recalls some of the time-traveling antics of Twin Peaks: The Return and Mulholland Dr. Another work, titled Every Girl’s Dream (2017), features a nude female figure embraced by a shadowy monster, along with the words “Sally said this NOT ME!”

Asked whether narratives play out in the paintings, Lynch said, “Yes, I love a narrative—a little story, a small story, as I say. I like to have something going on with the characters.” Prodded for more information, he continued, a little cryptically, “Sometimes the story comes first, but sometimes the narrative comes out of the work later. It depends how it goes, but again, I like to have the thing feeling a certain way. If it wasn’t for words, it just wouldn’t be complete.”

The paintings are raw and almost gross because of their chunky, tumorous-looking globs of material. “I use a bunch of different things,” he said. “I like this thing I call ‘organic phenomena’—when you mix this with that, you get a fantastic thing sometimes. It’s total mixed media—all different kinds of things in there.” What exactly constitutes such “things” remains a mystery: With a knowing laugh, Lynch declined to identify all his materials. “But I use a lot of glue, acrylic paint, watercolors, tempera, cigarette ashes,” he said. “I use, you know, a whole bunch of different things.”

David Lynch, Every Girl’s Dream, 2017, ink and watercolor on paper.

FLYING STUDIO/COURTESY THE ARTIST AND KAYNE GRIFFIN CORCORAN

Lynch has taken to calling his studio practice his “art life,” though his work in different mediums intersects. From an early age, long before he even thought of making movies, Lynch knew he wanted to study art. In high school, his friend’s father gave him a copy of Robert Henri’s book The Art Spirit, which theorized that art and life are one and the same, and that artworks are the records of creativity incited by unseen forces. He went onto study, from 1966 to 1967, at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Art. One of his first major mature works, Six Men Getting Sick (1967), was a painting that featured the heads of a few men on a panel. It initially included a projection that made it appear as if the men were vomiting, all while a police siren wailed. In certain ways, it could count as Lynch’s first film.

He insists he does not know much about contemporary art. “I know nothing about the L.A. art scene!” he said. “I don’t know anything about the New York art scene, the Paris art scene, the German art scene. In the same way with film, I’m not a film buff.”

He does, however, favor certain artists and styles. “I like childish, bad painting,” he said in reference to the French Art Brut painter Jean Dubuffet. He dismissed conventional figurative work as “flat” and “like a furniture-store sort of thing,” and prefers instead Dubuffet’s “distortions.” Other artists he likes include Julian Schnabel, Anselm Kiefer, Edward and Nancy Kienholz, and Georg Baselitz.

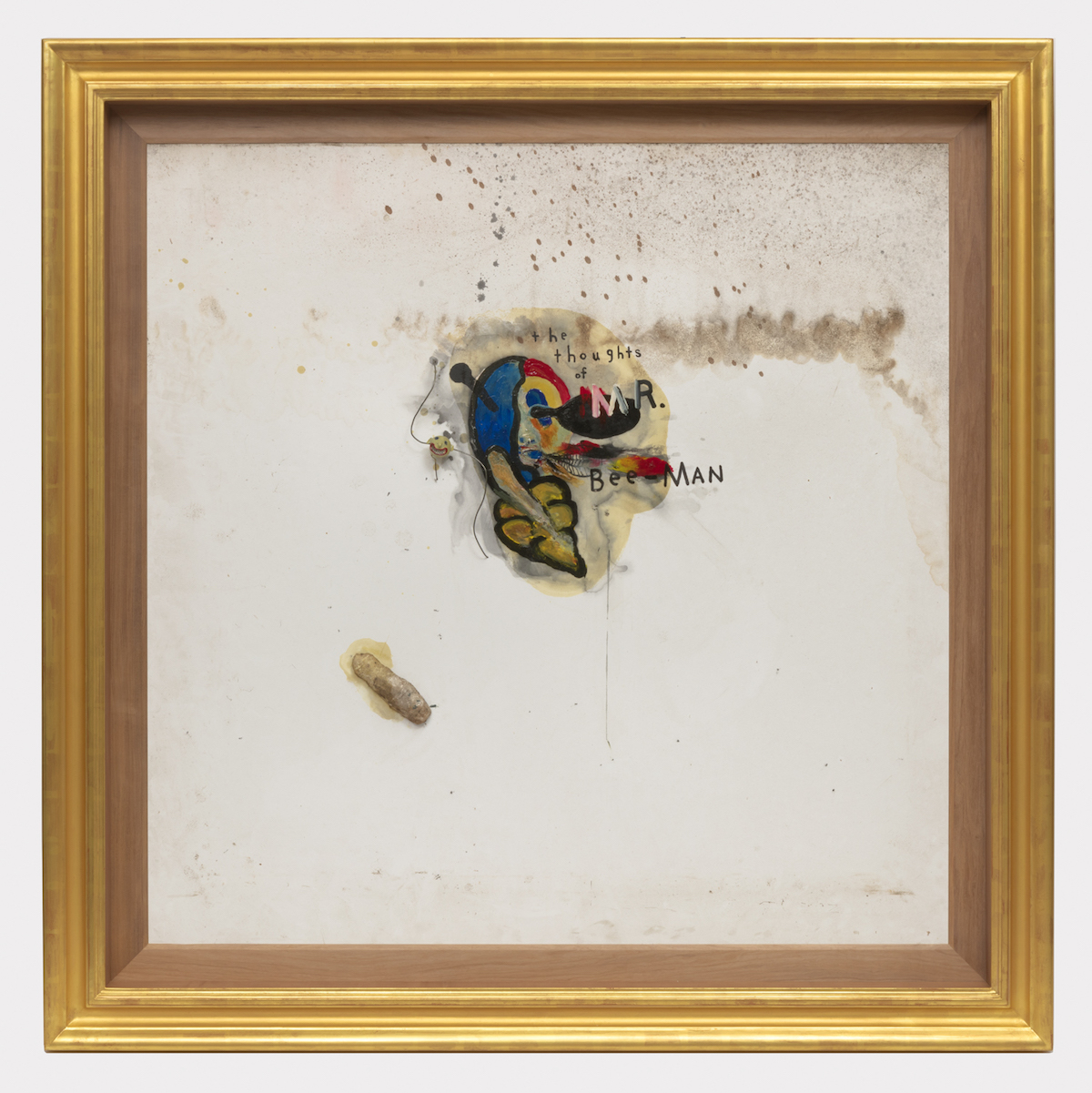

David Lynch, The Thoughts of Mr. Bee-Man, 2018, mixed media painting.

ROBERT WEDEMEYER/COURTESY THE ARTIST AND KAYNE GRIFFIN CORCORAN

And then there is Francis Bacon, whose work Lynch can distinctly remember seeing as a young man at New York’s Marlborough Gallery in 1966. “He’s a huge inspiration,” Lynch said of the painter of meat slabs and tortured men in inscrutable rooms. In his show at Kayne Griffin Corcoran, he alludes to some of the formative Bacon works he saw, which were framed in gold and placed under glass. “It’s framed like a stage—you are looking through something to see,” he said. “This is thrilling to me.” His new works are similarly set in gold and silver frames he crafted himself.

Strange combinations of animals and humans recur. In one work, The Thoughts of Mr. Bee-Man (2018), a cartoonish person appears to have merged with an insect form, with a body that has become a stinger. What might he be thinking about when producing such hybrids of animals and humans? “I’m thinking about animals and humans,” he said, as if the answer said all that could be uttered on the subject. Certain hybridizations please him more than others. “I like dogs with a human head. I’ve done sheep with a human head. I like combos like that.”

Lynch explained that he paints every day. “That’s all I do, just paint in my studio,” he said. He also maintains a practice of Transcendental Meditation that aids in his work process. “People who have this ability to transcend start expanding consciousness with those all-positive qualities, and it serves the work,” he said. “Ideas flow more freely—you’re happier in the work. It’s a form of meditation that allows a human being to experience the deepest eternal level of life. And in the field that you transcend is unbounded creativity, intelligence, love, happiness, energy, peace, power. It’s a huge blessing, for the work and for life.”

[ad_2]

Source link