[ad_1]

D.A. Pennebaker, the revered filmmaker who revolutionized the technology and style of contemporary documentaries, died Thursday at his home in Long Island, New York. He was 94.

The list of U.S. filmmakers with notable influences on popular culture is lengthy, but few can claim to have changed the medium altogether. Pennebaker did so in at least two significant ways.

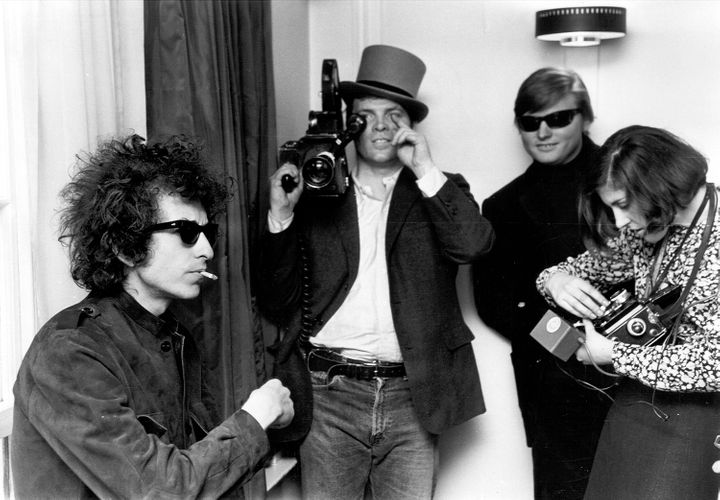

While making concert films in the 1960s, he helped to conceptualize a proto-form of the music video. Pennebaker captured Bob Dylan holding index cards with words from “Subterranean Homesick Blues” at the start of the (apostrophe-less) 1967 classic “Dont Look Back,” arguably the most influential concert film in history. Later, to record artists onstage for 1968′s “Monterey Pop,” he helped to construct a portable 16mm camera capable of blending sound and image.

“The whole idea was to be able to follow people around and shoot dialogue,” Pennebaker said in 2015. “You could shoot stuff that would sync up with music and talking and everything else. We had five of those at the time. We were making them in our office, practically.”

It became an industry standard, and much of the famed concert footage that still circulates from Jimi Hendrix’s and Janis Joplin’s short careers can be credited to “Monterey Pop.” These accomplishments made Pennebaker a pioneer of cinéma vérité and a key chronicler of the counterculture that defined much of the 1960s and ’70s.

Pennebaker, who served in the U.S. Navy and held an engineering degree from Yale, never expected a career in film. He was bored by a job building power stations, so he joined forces with a man shooting newsreel footage aboard. That opened the door for him, ultimately inspiring Pennebaker to join fellow cinéma-vérité forerunners Robert Drew, Richard Leacock and Albert Maysles in making 1960’s “Primary,” about the fight for that year’s Democratic presidential nomination between John F. Kennedy and Hubert Humphrey.

More than three decades later, Pennebaker ― alongside his wife and frequent collaborator, Chris Hegedus ― directed one of the most revealing pieces of political theater ever committed to film. 1993’s “The War Room” went behind the scenes of Bill Clinton’s presidential campaign, providing an unprecedented look at election strategy-making. The film earned an Oscar nomination for Best Documentary Feature and made stars out of George Stephanopoulos and James Carville, who were Clinton’s advisers during his 1992 campaign.

“We became regular participants in that huge basketball-court-sized office they had,” Pennebaker said. “We weren’t making a film, we were just hanging out, making a kind of home movie. That’s how it had to feel. … George laughed all the way through it. At the end, he said, ‘If I’d known you were going to do this, I’d have never let you in!’ Their best impulses fooled them into letting [me] in. Same with Dylan.”

In between, Pennebaker helmed some of the past century’s most notable documentaries. He reteamed with Dylan for 1972’s “Eat the Document,” contributed footage to Martin Scorsese’s “No Direction Home” and spearheaded similar projects with the Plastic Ono Band, Alice Cooper, Little Richard, David Bowie, Jimi Hendrix and Depeche Mode.

Pennebaker’s achievements cemented the concert film as a ubiquitous genre that combines musical performances with backstage footage. The format has since attracted Talking Heads, Madonna, Jay-Z and Justin Bieber, among many others.

Pennebaker mostly stayed close to that terrain over the course of his career, making films about a Broadway play starring Carol Burnett (1997’s “Moon Over Broadway”), a concert featuring the artists who recorded the soundtrack for the 2000 film, “O Brother, Where Art Thou?”, and a one-woman show starring Elaine Stritch (2002’s “Elaine Stritch at Liberty”).

Pennebaker also had an eye for human-interest issues, documenting the political fight surrounding President Jimmy Carter’s natural-gas bill (1978’s “The Energy War”), Norman Mailer’s public debate with feminists (1979’s “Town Bloody Hall”), French chefs competing for a prestigious distinction (2010’s “Kings of Pastry”), and the Nonhuman Rights Project’s efforts to secure legal rights for animals (2016’s “Unlocking the Cage”).

Born Donn Alan Pennebaker in Illinois, the director, whom most called Penny, is survived by Hegedus. Pennebaker and Hegedus married in 1982, six years after she joined his filmmaking company. They remained professional partners throughout the years, co-directing numerous movies and producing each other’s work.

Pennebaker was married twice before Hegedus. From his three marriages, Pennebaker had eight children, including two with Hegedus. In 2013, he was awarded an honorary Oscar, celebrating a career that has prompted audiences to readjust their view of documentary filmmaking. Before his death, he was working on a memoir.

“It was interesting to shoot history as it happens, without anyone demanding a huge story,” Pennebaker said.

REAL LIFE. REAL NEWS. REAL VOICES.

Help us tell more of the stories that matter from voices that too often remain unheard.

[ad_2]

Source link