Curator Lauren Haynes Revisits a 1966 Profile of Spiral, Pioneering Black Art Collective

In 1963, 14 Black artists in New York formed the Spiral group. They met regularly to discuss issues affecting Black artists of the time, mounted one exhibition together, and disbanded within a couple years. Recently, artists and art historians have been revisiting Spiral’s significance, especially the ways in which the group intentionally complicated the relationship between art and Blackness. One of the few extensive accounts of Spiral’s activities in the press appeared in a 1966 issue of ARTnews. For a fresh perspective on that article—“Why Spiral?,” in which Jeanne Siegel quoted several prominent artists in the group—ARTnews connected with Lauren Haynes, a curator at the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Bentonville, Arkansas, who organized a survey exhibition of Spiral at the Studio Museum in Harlem in 2011. Speaking in June, just days after a group of Black artists and workers banded together to pen a letter about the Black Lives Matter movement in the wake of the police killing of George Floyd, and just a few weeks after the death of Spiral member Emma Amos, Haynes said, “It’s interesting to reread this article in this current moment.”

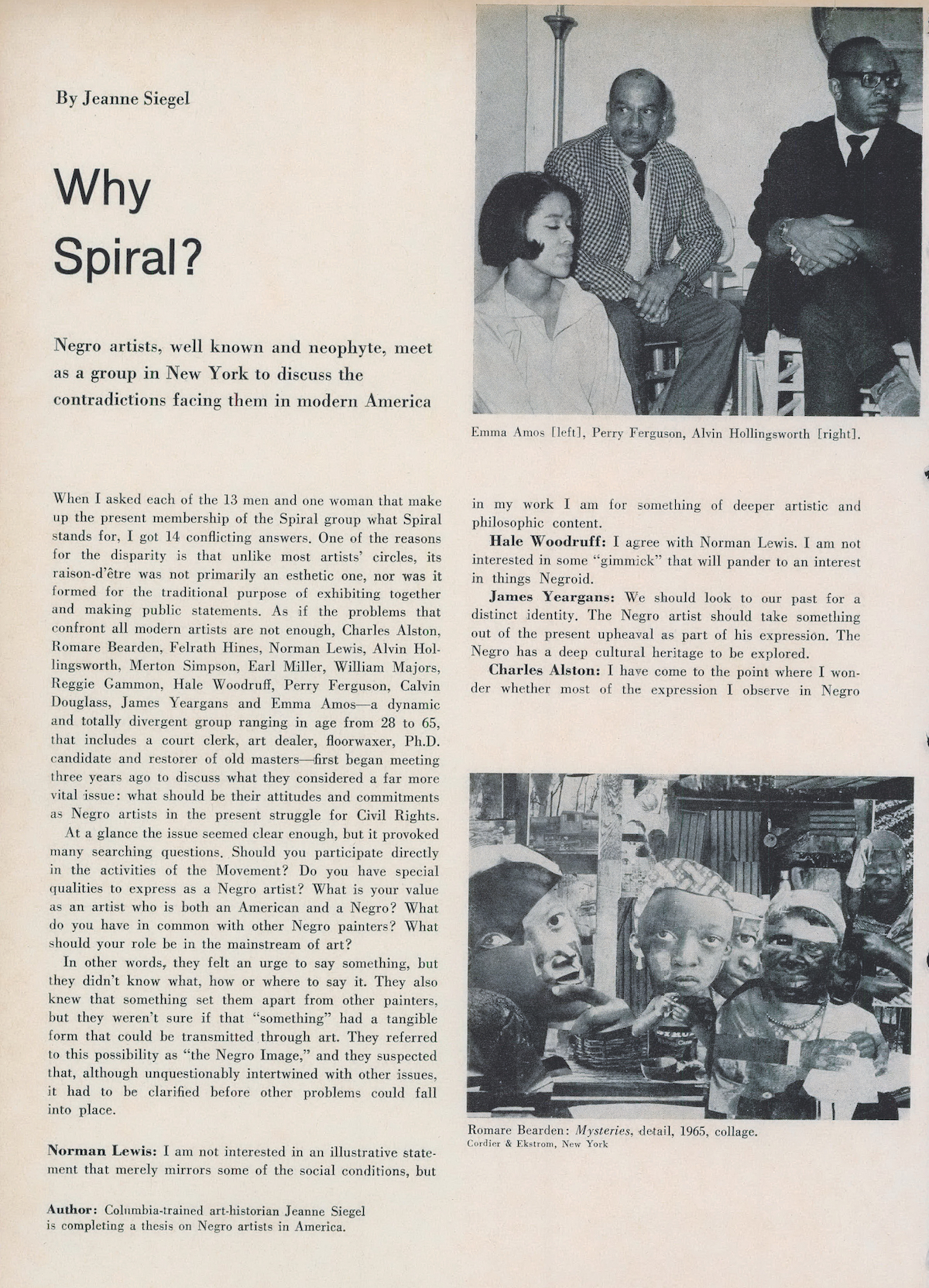

Jeanne Siegel, back then: When I asked each of the 13 men and one woman who make up the present membership of the Spiral group what Spiral stands for, I got 14 conflicting answers. One of the reasons for the disparity is that unlike most artists’ circles, its raison-d’être was not primarily an esthetic one, nor was it formed for the traditional purpose of exhibiting together and making public statements.

Lauren Haynes, now: I don’t think they agreed [on many issues]. That’s the beauty of the collective coming to bear as we’re looking back on this and thinking about how we talk about Black abstract artists.

[Read Jeanne Siegel’s 1966 profile of Spiral in full.]

Norman Lewis, then: “I am not interested in an illustrative statement that merely mirrors some of the social conditions, but in my work I am for something of deeper artistic and philosophic content.”

Hale Woodruff, then: “I agree with Norman Lewis. I am not interested in some ‘gimmick’ that will pander to an interest in things Negroid.”

Haynes, now: So many artists were answering questions so many of them got at the moment: What does it mean for you, a Black artist, to make art in this political moment? Are you supposed to talk about only works that uplift the Black experience? Are you supposed to make works only about this current moment, or can you make abstract work that’s not necessarily tied to it? That’s why someone like Hale Woodruff might feel as if this could be a gimmick.

Emma Amos, then: “We never let white folks in. I don’t believe there is such a thing as a Negro artist. Why don’t we let white folks in?”

Haynes, now: I was lucky, years ago, to do a studio visit with Emma Amos around the time of the Studio Museum show. We got to talking about Spiral and her experience. She talked about how she felt like she was let in—there were other Black female artists who could’ve been a part of Spiral. Because she was younger, there was an expectation that she would take notes and get coffee, not be an active participant.

Alvin Hollingsworth, then: “We blackballed all the Colored folks too.”

Romare Bearden, then: “The Negro artist is unknown to America.”

Haynes, now: People who are interested in art tend to turn to artists to solve problems that aren’t theirs to solve. This is an example of artists coming together to try to do that. [Spiral’s artists] didn’t come away with answers—they didn’t say, “This is the six-step plan we need, this is what we need to do.” But the fascination [with Spiral today] comes from the fact that they were trying to do something, that they wanted to figure this out.

Published at Wed, 04 Nov 2020 22:15:28 +0000