[ad_1]

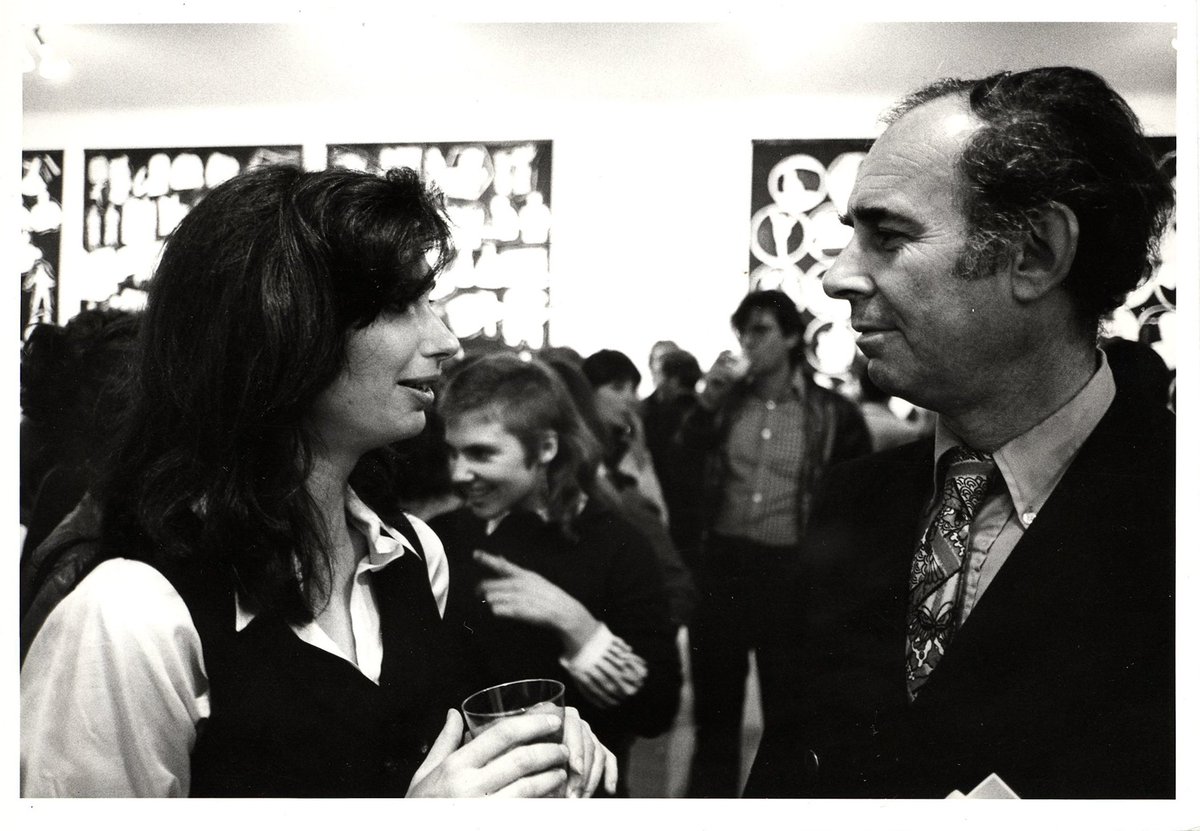

Sherrie Levine and Irving Sandler at Artists Space in New York at the opening of “Pictures” in 1977.

COURTESY ARTISTS SPACE

This past weekend, the beloved critic Irving Sandler died at age 92. As an editorial associate at ARTnews, between 1956 and 1962, Sandler produced a series of reviews and interviews with prominent Abstract Expressionist artists that cemented his place in history as one of the foremost critics of modern art. As the times changed, his career did, too—he cofounded New York’s Artists Space in 1972, and he continued to seek out new art, supporting the work of younger artists and critics over the years. This week, ARTnews reached out to several critics and artists, and asked them for remembrances of Sandler. Their responses follow below.

Lilly Wei

Critic

I’ve always considered Irving Sandler a much-loved, one-of-a-kind presence in the New York art world. He immersed himself in it as a prolific writer and teacher, and as an attendee of lectures, panels (many of which he was on), openings, and fundraisers. He sat on boards, advisory councils, grant committees, and so on, all with unflagging zest, up to just three weeks or so before his death. When told accusatively that he would attend the opening of even an envelope, he happily agreed that he would.

He came of age as a critic in the heyday of Abstract Expressionism, a movement that he helped define as a triumph for American mid-century painting. He truly loved artists and the art that they produced, and he saw his role as that of an advocate, not an adversary. A natural raconteur himself, he loved artists’ stories, and he loved his stories about them. He told me one about [Willem] de Kooning—who was being filmed—working in his studio, attacking his canvas with gusto, moving about rapidly, paint flying, arms akimbo. When finished, Irving asked him: what would he do with the painting? De Kooning said he would rip it up. He didn’t paint like that. He sat in a chair and looked and looked, and then he might make a mark—and then would look some more.

Laurie Fendrich and Peter Plagens

Artists

Our real friendship with Irving Sandler and Lucy Freeman Sandler goes back to our moving to New York in 1985. Irving was the nicest smart man, and the smartest nice man, we have ever known—a man who wore his erudition about art lightly. Instead of spending most of his time theorizing and pontificating, Irving—to paraphrase J. A. D. Ingres in his Academy class—looked, looked some more, and then continued to look at art. There was a friendly joke in the art world that there had to be many more than one Irving Sandler for him to show up at as many exhibitions as he did. Even when he was in his late 70s and 80s, he didn’t sequester himself among shows of painting, his first and greatest love, but let the tide of current art history override aesthetic sentiment. He looked and thought and spoke—civilly and empathetically—about a whole lot of art that wasn’t, to put it mildly, his cup of tea.

Irving’s lack of intellectual vanity was remarkable. He once told us, “There’s not much to know about me other than that I like meeting artists and I like yakking.” But, like one of those stoical Western movie heroes, Irving Sandler didn’t go into saloons—or artists’ bars—and throw his weight around just to show off. He could, however, deliver a punch when he had to. Asked while giving testimony in an art-fraud case if it was “correct” that he was “an expert” on Abstract Expressionism, Sandler replied, “No, that’s not correct. I am the expert on Abstract Expressionism.” And there was the time several years ago when, after listening to a lecture given by an art historian so infatuated with theory that he sounded like a wannabe sociologist, Irving stood up in the audience and, in a voice tinged with controlled rage, said, “Yes, but you’re forgetting there’s this thing called art.”

He was a brilliant art historian who rejected academic ideas about art theory and instead engulfed himself in the intense heat of art history as it was being made, by showing up on the field. Irving certainly conveyed this attitude to artists and that explains why he genuinely felt at home with them, and why, in turn, artists felt he understood them. He was always interested in how things were going with our careers, and he always showed up, as he did for so many other artists, for every show we had in New York.

Irving was as socially and politically concerned—on the Left—as anybody we knew. It’s just that he put art and artists first, and didn’t ask of the former, as did John Berger, how individual works of art would help achieve the political “liberation” of humankind. And he didn’t expect artists to be first and foremost propagandists for political causes. He was supremely sympathetic to artists being, well, artists, and in all his landmark books, he tried to tell the story from their “consensus” (a favorite word of Irving’s) point of view.

Irving was sanguine about age, and would call us—we’re both in our 70s—“you kids” when we saw him socially. Over the past couple of years, we had many conversations about the state of the art world in which he argued that the end of “polemics”—heated arguments over the quality and worth of art that had marked the era of Abstract Expressionism—was flattening art. Even so, he maintained to the end a radical openness to new art—a principled aesthetic based on being democratic and outward-looking, rather than elitist and exclusionary.

Irving never lost his faith that it’s in the nature of art to harbor the new and the fresh. The hard part is figuring out what that is. After Irving passed away, someone we know in the social sciences who knew we were friends with Irving sent a note saying that his wife recalled taking a course in the 1970s at SUNY Purchase, taught by what, to her 18-year-old mind, was a chain-smoking genius. “He changed the way I saw art, and he changed my life.” We were already decades into being artists when we met Irving, so his effect on us wasn’t quite as radical. But, in a deep and quiet way, it profoundly enhanced the way we saw art, renewed our faith in it, and made our lives all the better for it.

David Row

Artist

As Americans, we are often very dismissive of the traditions that preceded us, but we are also subject to myths regarding the past. For artists of my generation, growing up in the late 1960s, Irving Sandler was a vital link to the era of the Abstract Expressionists, the Club, the Cedar Tavern, and the Tenth Street scene. It was the work of that generation of American artists that inspired many of us to be painters, and Irving knew those artists and contextualized them in a very real and direct way. Unlike the rough and tumble of much of that generation and the one that followed it, however, Irving was driven less by an ideological position and more by his own curiosity and the conversations that exposed possibilities and attitudes of individual artists.

That is the reason he was not fixed in positions that defined only one era. Irving was no pushover, but he was open to ideas that were at times antithetical to the zeitgeist of the times in which he made his original mark. As his accomplishments testify, Irving went on to make great contributions to the art world of my generation and beyond, including establishing Artists Space with Trudie Grace, writing countless reviews of contemporary shows, and participating in formal and informal discussions of the state of the art world that continued right up through the first half of this year. I was privileged to know him and will miss him terribly. My heart goes out to Lucy Freeman Sandler, another formidable intellect focused on the visual arts, who must now soldier on without him.

Phong Bui

Cofounder and Artistic Director, the Brooklyn Rail

Irving was one of the early supporters of the Brooklyn Rail. We met as early as 2003, 2004. Those were the days when I used to be very proactive in organizing panel discussions about art. We organized, for instance, a big panel discussion about Philip Guston’s work at Pierogi gallery [in New York]—Irving and [his wife] Lucy came out. He was amazing. We all know he’s a legend, so his presence was very important. He asked very thoughtful questions, and he encouraged all of us to do the same. There was a social ease to Irving, the way that he would talk to people. And, of course, I joined the boards of AICA-USA and the Sharpe-Walentas Studio Program [Sandler was involved in both organizations]. Irving and I were social activists, in a way.

Irving had an epiphany when he saw Franz Kline’s painting Chief, from 1952. That, to me, is a very profound thing. James Joyce spoke a great deal about everyday epiphany, which all of us is capable of perceiving if we pay attention. Irving paid attention—he had no business confronting Chief. But there he was, right in front of it, feeling the power of the painting. It’s the everyday epiphany that Joyce described, and Irving allowed it to change his life. Don’t you think that’s remarkable? . . . Irving was able to be really open, to remain super fresh and really alert. That’s what I learned from Irving—what he called “on-the-spot history,” which means being there, observing, absorbing, processing, looking, seeing, and, above all, asking what, why, and when the object was made, and under what conditions.

I put Irving to work. I asked him to interview Roberta Smith, Ken Johnson, Jerry Saltz, and he was ready and eager. He didn’t feel that he was someone who had an established place in the art world and that, because of that, he could sit on his laurels. He was a fighter for his interests, and he got involved in the Brooklyn Rail. He wanted to pass the baton on to the younger people. . . . Irving didn’t want to be pigeonholed as an Ab-Ex person. My grandmother once said, “A remarkable young person has an old soul. A remarkable old person has a young soul.” Those remarkable people switch at some point, and at some point in our friendship, Irving became young.

Ruth Appelhof

Director Emerita, Guild Hall of East Hampton

Irving Sandler is a name we will remember for generations to come. He helped America, and the rest of the world, understand the great talents we had in mid-twentieth century in this country. He identified the New York School as groundbreaking and unparalleled. Many have taken issue with Sandler because he left a few good artists out of his significant art-historical survey, The Triumph of American Painting: A History of Abstract Expressionism, published in 1970, but his basic recognition that there was a seismic change in the art world at the time was ground-breaking.

My own story is as a graduate student at Syracuse University in the 1970s. I was preparing to teach a course for SUNY on the Pre-Raphaelite period and doing research at the British Museum Library. While standing on line in the cafeteria, I introduced myself to Irving. We had lunch and began to talk about the Abstract Expressionist artists and his thoughts on their contributions. As a feminist, I wondered why he didn’t include Lee Krasner in his survey. He encouraged me to pursue Krasner for my master’s thesis. As the first spark of serious interest in the artist, his suggestion led me to a personal relationship with her. She invited me to spend the summer of 1974 in East Hampton interviewing her for my graduate degree.

Sandler and I kept in touch over the years. I recall his being a guest speaker at several of the museums I directed. Finally, just last week, I interviewed Sandler for the memoir I am now writing on Krasner. He remembered our first conversation some 40 years ago.

As I was leaving the apartment, Lucy Freeman came to the door with her husband to say goodbye. I turned to him and said, “Thank you for this wonderful interview and for all the years of encouragement and advice. Your presence in my life and confidence in my work has been the one true ballast.” And, again, “Thank you for seeing me today.” Irving Sandler looked at his wife and nodded as if to say, “See, my lifelong passion to share art and ideas with others is recognized and appreciated.” Of course, he was right!

Kim Levin

Critic

Irv Sandler, with his benevolent but stern sense of decorum—modest, self-effacing, avuncular—didn’t lend himself to anecdotes. He maintained his role as a witness, “a sweeper-up after artists,” as he famously put it in the title of his memoir. As secretary of the Club and patron of the Cedar Tavern, he was an acute observer of the small messy art world of his own generation of New York Abstract Expressionists. He was there with them at the time, documenting as they were happening the lives and works of the artists, their anecdotes, and details and history. He was the anti–Clement Greenberg. As art historian and professor, he realized the crucial importance of primary sources: he was the Witness to art. In the process, he became an integral part of that history, which for the future may be the most important role. As an art writer, he continued to observe and make sense of the New York art scene for more than half a century. And he continued to participate fully in the art community, first as manager of the artist-run Tanager Gallery on Tenth Street, then as cofounder of Artists Space; as president of the U.S. section of AICA; as curator; and as director of the Neuberger Museum. He managed to make sure the history of art in New York in the second half of the twentieth century remained available to the future. It was always a great pleasure to meet him and his wife, Lucy, a distinguished scholar in medieval manuscripts, at gallery and museum openings. He quoted me occasionally in his books, which I took as a high honor, for in those days it was more customary to borrow from than to quote a younger female critic. He was our Vasari, and he will be missed. But he has left us with a final gift: his first novel, Goodbye to Tenth Street, will be published this fall.

Alex Greenberger contributed reporting.

[ad_2]

Source link