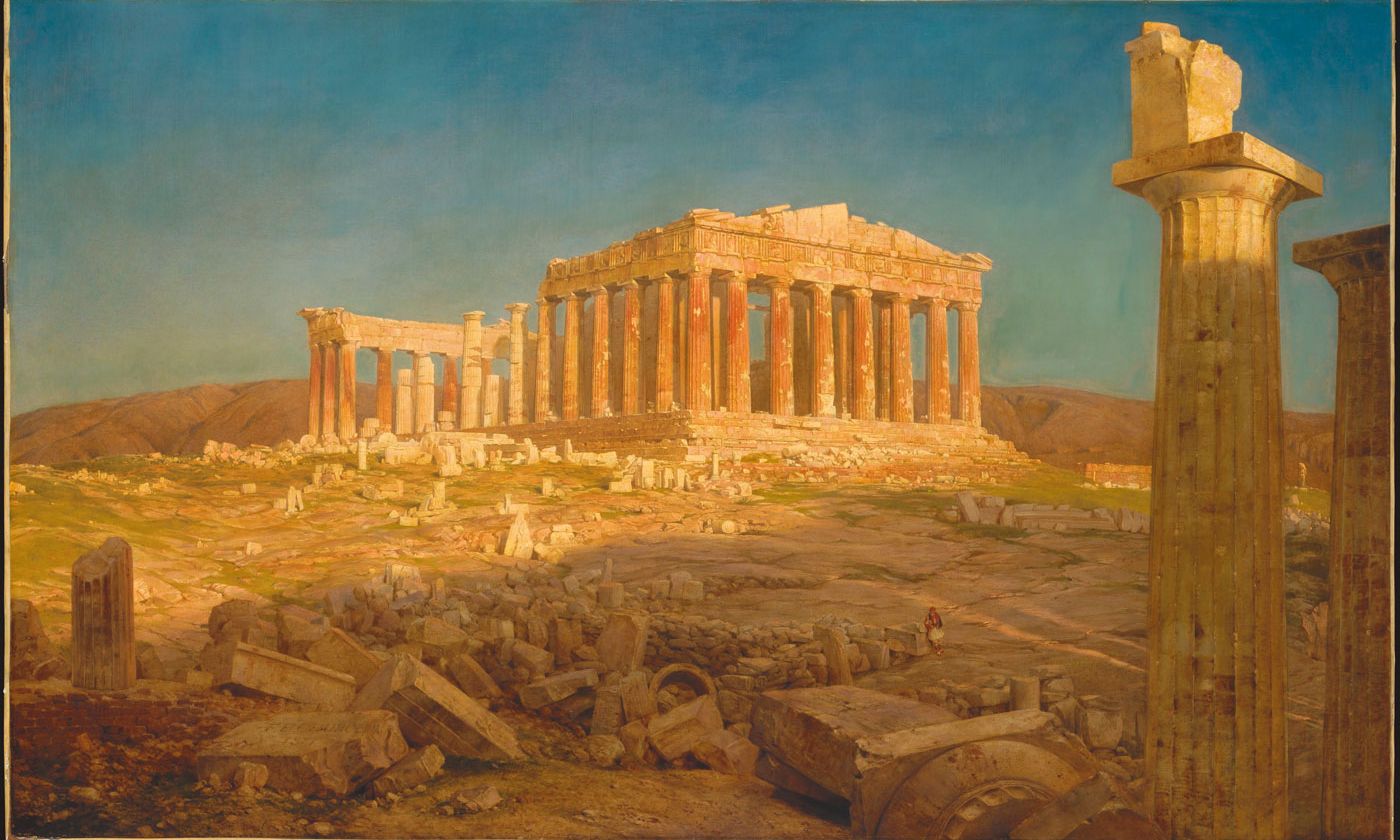

Frederic Edwin Church’s 1871 painting, The Parthenon. The temple had already suffered damage from earthquake, bombing and occupation before Lord Elgin’s arrival in 1801

Courtesy Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

The Athenian Parthenon has survived two millennia of foreign occupations and vicissitudes, with Lord Elgin’s removal of its celebrated sculpted marbles in 1801-05 the best remembered and most debated—and one still open to remedy. The great temple to Athena, standing proud on the Acropolis, has also proved a subject of almost inexhaustible fascination to architects, artists (whether they visited or not), grand tourists and historians. In Who Saved the Parthenon?, his last work on the subject, William St Clair, a lifelong civil servant in the UK Treasury who otherwise devoted himself to classical and modern Greek scholarship and to detailed questions about the ownership of the Parthenon Marbles, reveals a wealth of hitherto unknown material about the Acropolis, the Ottoman occupation of Greece, and the nine-year Greek War of Independence from Ottoman rule of 1821-30.

St Clair’s expertise ranged from the monuments on the Athenian Acropolis to 19th-century romantics (Shelley and Byron) and the Greek War of Independence. He demonstrated his commitment to open-source publishing by co-founding Open Book Publishers and uploading as many images as possible on Wikimedia Commons. St Clair died in June 2021 before seeing Who Saved the Parthenon? published. In this book he also announced a forthcoming companion volume on the Parthenon specifically in Classical times, plus a book about St Paul.

In this daunting tome, St Clair provides a survey mostly of Athens before and after independence in 1830, with a focus on how the Acropolis monuments survived and what drove the post-war removal of the medieval and later building accretions. St Clair set out to dismantle the old cliché that the Parthenon’s partial destruction was caused by the Turks. An earthquake of 1640 had damaged the Propylaia (the ceremonial gateway) and in September 1687 the Venetian general Francesco Morosini intentionally fired a shell (or “bomb”) at the Parthenon (the temple dedicated to Athena), where gunpowder was stored by the Ottomans, later boasting in the official report of his “lucky shot”. St Clair does not mention that the explosion killed 300 Turkish women and children taking refuge within the monument, the ensuing fire burning for two days. The shell itself, recently identified by the archaeologist C.N. Reeves, was a 2cwt two-handled mortar bomb, and was brought back to Eton College in the 1860s by Philip T. Godsal. An interesting but omitted detail is that Morosini only occupied the Acropolis for a few months before abandoning it to the Ottomans, after his appointment as Doge of Venice (1688-94).

St Clair describes the situation in Athens in 1809 under the Ottomans, with a defined Greek population served by 39 churches and 80 chapels, whereas the minority underclass of Greek-speaking Turks had only 11 mosques, one religious school and three Turkish baths. The Ottoman millet system (the means of administering the separate religious communities) extended a certain religious independence to these communities, though they remained separate, and for some inexplicable reason Jews were not allowed to live in Athens (although they thrived in Thessaloniki). By this time Greeks did not consider themselves the heirs of Classical [pagan] culture, but of the Christian Byzantines. Two events paved the way for the rediscovery of Classicism: the finding and printing in 1516 of the geographer Pausanias’s second century AD guide to Greece; and the publication of all ancient references to the Acropolis by Johannes van Meurs (Cecropia, 1622).

Greece was mostly off limits to foreigners because of the risks of Barbary pirates and slavers, and only the intrepid, well-financed foreigners, with permission (a “Firman” letter) could visit the country. (In 1836 one traveller covered 2,000 miles over a period of 22 weeks at a cost of £230.) Between the 17th and 19th centuries, gushing illustrated travel books were produced for the armchair traveller—E. D. Clarke’s early 19th-century illustrated volumes netted him £6,000—sparking the imagination of figures like J.M.W. Turner, who painted numerous images but never managed to visit. So, too, for that matter, the German art historian Johann Joachim Winckelmann. Guillet de St Georges never left his armchair to produce his 1675 travel guide and was exposed as a fraud by the Lyonnais medical doctor and antiquary Jacob Spon, who travelled to Constantinople (Istanbul) and Athens with George Wheler. Often romantically illustrated, many travel accounts, according to St Clair, constituted “an appropriation of revived classicising literary tropes”, avoiding mention of the gory Ottoman impalements or triumphal skeletal heaps of executed men (over the age of 14), and the punitive enslavement of women and children.

Western visitors did not doubt that Greeks were descendants of the ancients, whereas the pagan past and Pausanias’s description was unknown to Greeks in Greece. St Clair states that the Orthodox church treated the ancient buildings as “defeated pieces of built heritage”, reusing them as churches, while opposing the independence struggle and peddling the Providentialism doctrine that God had willed the Ottoman presence, thus requiring a duty to obey the sultan. It was the Greeks in the diaspora—with their emerging nationalism—who appealed in vain to Catherine the Great of Russia in 1790 for help to overthrow the Ottoman yoke on the heirs of classical antiquity.

St Clair’s research and study of tens of thousands of contemporary papers relating to the British Embassy (now mostly at the National Archives in Kew), with eyewitness accounts and messages intercepted under the pretence of quarantine (the Ionian Islands were a British Protectorate), provides details of the European presence ranging from clerics to visiting architects (C.R. Cockerell), geologists (William John Hamilton), numerous men of letters and diplomats. Besides the usual French and English diplomats (including Stratford Canning), there was the Austrian Georg Gropius (who married a Greek who bore 11 children). Diplomats travelled freely conveying messages and orders even to the Barbary states. And some could dabble in the dealing of antiquities, as did Gropius.

The Greek Revolution took most by surprise, but French and British philhellene naval and military men acted quickly to advise Greek fighters. The first assault on the Acropolis (29 April 1821) ended with its foreign negotiated surrender (9 June 1822), but with 512 Muslim bodies left behind and 800 captives, who were eventually butchered (as the Greek and Turkish fighters did not use the elaborate European “lens of truces, parleys, surrenders, treatment of prisoners”). The Siege of Missolonghi ended in defeat in April 1826, with 2,750 butchered Greeks (in a pyramid of skulls, as described in contemporary accounts), self-immolation or enslavement of women and children whom Westerners tried to ransom back.

Eugène Delacroix’s Greece on the Ruins of Missolonghi (1826) depicts the siege that led to 2,750 deaths and the enslavement of women and children

Courtesy Musée des Beaux-Arts de Bordeaux

It was the Ottoman exhibition of sacks of human heads in Constantinople, as described by Western newspapers, that repulsed and raised the profile of the struggle for justice and freedom. The Turks re-took the Acropolis on 7 June 1827, but a Greek revolutionary force of 10,000 failed to retake it (2,000 were killed) until the Allies and the machinations of the British navy at Negroponte forced the Ottomans off the Acropolis and out of Attica in 1833. The Ottomans had respected the monuments thanks to the prescient act of the British ambassador, Stratford Canning, in extracting an order from the sultan, which he skilfully copied to the Ottoman Commander Reschid: the latter complying perhaps to demonstrate his army’s discipline to the Europeans.

After independence, a re-Hellenising impulse cleared the Acropolis of post-Classical accretions, excavating down to bedrock. Following an earthquake in 1895, the Greek government appointed three international architects who realised that the Parthenon was “an elaborate complex of interacting weights”, but that Lord Elgin’s removals (see below) had put strain on the architraves. Fortunately, in 1805 the French ambassador had prevented Elgin from further damaging removals on the west facade by securing a desist Firman. Excavations revealed a cache of pre-Persian War sculptural dedications, many intentionally damaged and left only to be buried a generation later. The excavations (120,000 cubic metres of soil dumped from the summit) in 1840 revealed a sculptors’ atelier, though by stages the tools—considered relatively unimportant—disappeared and were subsequently lost or were given away to visitors, as was the case with an ivory fragment, possibly from the chryselephantine cult statue of Athena. Re-hellenisation involved the dismantling of the Frankish Tower for which the German amateur archaeologist Heinrich Schliemann offered funds (in 1874), all resulting in a muddled and unsuccessful experiment, according to the author, in “experiential heritage”.

St Clair anecdotally recounts that Benjamin Disraeli (later UK prime minister) had hoped to join Reschid’s forces in 1830, detesting the pieties of philhellenism and Byronism, and viewing the Greeks as descended, in his own words, from the “Kalmuck and the Negro”. He was flattered to interview Reschid, who was “daily decapitating half the province”. Skeletons remained on the Acropolis for years, and visitors used skulls as props for images on the transience of life, whereas others collected them for phrenological studies. The war tally revealed staggering statistics that far outnumber those of the Italian Risorgimento three decades later. Athens was left with a population of 350 and few houses standing. On Chios alone, 23,000 men were killed, and 47,000 women and children were enslaved. In the Peloponnese, the Greek population of 458,000 Orthodox and 42,750 Muslims was reduced to 400,000 Orthodox only. On the island of Psara, Ambassador Canning learned of self-immolation and saw 500 displayed heads. Throughout, survivors were starving and described as the walking dead. St Clair observes how an “imperialising attitude that came easily to the 19th-century west” brought missionaries, who made no converts and, according to J.L. Stephens’s 1838 account, were unable to “purify” the “follies, absurdities and abominations of the Greek faith”. The Christian Providentialists—who believed all events were controlled by God—followed, in order to experience where the firebrand St Paul preached in AD60. French and Italian Catholics were latecomers on these Bible land tours, with stopovers in Pompeii to demonstrate God’s wrath when man rejects Christianity.

Who saved the Parthenon? is an immense undertaking—660 pages, six primary source appendices, an 105-page bibliography and 195 figures—but there are glaring omissions: for example, the extent of the damage to the Parthenon’s east pediment and the north and south friezes by 5th-6th-century Christians building their church within it, their defacement of the metopes (carved plaques), and the later 12th-century destruction to the east frieze in enlarging the apse.

Most baffling is the omission of a plan of the Acropolis. Chronologically, the text is somewhat chaotic and anecdotal, with some rabbit-hole excurses (cognition, theocratic spirit, the meaning of the word deisidaimonesteroi etc). Some mentions by St Clair are abrupt and casual: for example, the use of explosives in clearing the Acropolis after the revolution; a headless caryatid on the ground; the naval battle of Navarino; which isles belonged to the de facto independent Peloponnese). Other brief mentions of treaties and events such as the Auspicious Incident of 15 June 1826—when 4,000 Janissaries, Ottoman elite infantry, were burned in their barracks and the remainder decapitated in Thessaloniki’s White Tower, resulting in the French taking on the role to advise the Ottomans—drive the reader to execute Google searches. Despite its uneven coverage, that should not deter the inquisitive reader.

Whereas St Clair’s mission was to explain how the Parthenon survived its troubled history, and while he gives credit to the Ottomans where it is due, he does not express a view about the marbles’ return to Greece. In The Parthenon Marbles and International Law, Catharine Titi, writer and legal scholar in international law, examines how the marbles were acquired, the question of good title, and the various legal mechanisms that may or may not be employed to secure their return to Greece.

Titi begins by making the connection between Lord Elgin, English ambassador to the Sublime Porte of Constantinople, and Caius Verres who, while on official business as governor of Sicily (73-71BC), plundered art. The Roman statesman and lawyer Cicero brought a class action suit against Verres for his rapaciousness (extortion, torture and execution) while in office. Elgin had his enablers—or “finders”, as Lord Byron called them—and sent the chaplain Dr Philip Hunt, William Richard Hamilton and Giovanni Battista Lusieri to Greece to draw and make casts of monuments in Athens and on the Acropolis in particular.

Elgin’s stated objective was to decorate his home at Broomhall, but following his service in Constantinople, his incarceration in France by direct order of Napoleon Bonaparte and his desire to deal with his crippling debts (not even having remunerated his enablers), he chose to sell. Titi details the machinations of the enablers who used a vizier’s letter, a memorandum seemingly drafted by Dr Hunt for Elgin and known only in Italian, to begin removals from the Parthenon (56 of the 97 frieze panels, 15 of the 92 metopes and 20 pedimental figures). The letter allows for his Lordship’s

“five English Painters [not the hundreds working for Elgin] to observe, study and also draw…set up ladders [for]…moulding …ornaments and visible figures…undertaking when necessary to dig the foundations to find inscribed blocks that may have survived in the gravel…there is no harm in the said pictures and buildings being observed, studied and drawn…and that no objection will be made to the removal of some (qualche) pieces of stone with inscriptions, and figures…”

William Gell, The removal of the Sculptures from the Pediments of the Parthenon by Elgin, 1801 Benaki Museum

As Titi points out, that letter should not be mistaken for an official Firman, nor does it afford licence for removals from the Parthenon itself but from the ground, as much rubble was lying about. She also points out that the word “some” (qualche) should not be mistaken for the word “any” (qualsiasi). Apart from Byron’s poetic indignation, others who were present and who expressed their outrage including E.D. Clarke, Edward Dodwell, Robert Smirke and Hugh W. Williams, for whom the dismantling and breakages made “a quarry of a work of Phidias”.

Titi rehearses the Parthenon Marble retentionists’ arguments that include: a) modern Greeks were not descended from the ancient Greeks; b) much of the frieze was retrieved from rubble; c) the marbles were saved from destruction (as if altruism motivated Elgin); and d) those advocating their return are cultural fascists. She examines the questions put to Elgin and his enablers by the parliamentary select committee considering the purchase of the marbles and analyses the “evasive, muddled and contradictory” responses. The examination of the facts was perfunctory at a time when Britain was victorious over France and wished to profit culturally by such a rich acquisition.

In 1816 Elgin sought £62,440 for his expenses (bribes), whereas the committee recommended £35,000. Despite the MPs' representations against Elgin—“spoliation” (Thomas Babington); “breach of faith” (Serjeant Best); “unjustifiable nature of the transaction” (John Newport); and the question of “whether an ambassador, residing in the territories of a foreign power, should have the right of appropriating to himself and deriving benefits from objects belonging to that power” (Lord Ossulston); followed by the suggestion that the “marbles should be held in trust for Greece” (Hugh Hammersley)—the vote favoured purchase by 82 to 30. Titi suggests that the decision to purchase might have involved consideration that the marbles already belonged to the nation (Elgin was on official business and he took advantage of free transport by British warships). Thus, if the government purchased at its designated price, this would be cheaper than defraying Elgin’s inflated expenses. Purchase would also enable the government to disassociate itself from its official’s behaviour.

The author examines the various avenues in international law that Greece might now consider. In 1962 Cambodia won the case of the Temple of Preah Vihear against Thailand for which the International Court of Justice (ICJ) decided that the appurtenances of a monument belong to the sovereign territory. She points out that the UK restricts ICJ jurisdiction to disputes arising after 1 January 1987; furthermore, the British Museum’s position is that the marbles were legally acquired, thus the issue is one of debate and not of an interstate dispute. Titi examines the possibility of a remedy before the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR), as advocated by the international lawyers Geoffrey Robertson, Norman Palmer and Amal Clooney, investigating problems of admissibility (ECHR usually applied to minority and indigenous groups) without a good chance of success. She also examines treaty laws that include the Hague Convention, related to armed conflict and occupation, and the 1970 Unesco and 1995 Unidroit Conventions.

Titi opts for a diplomatic approach for the return (not “restitution”, which implies fault), and suggests some points for discussion including: the destruction and destabilisation of the Parthenon caused by Elgin’s removals; criticisms made at the time; the importance of the Parthenon and significance to Greece; the nation’s repeated requests for their return since 1833; the legal definition as immoveable parts of a building (as per the Temple of Preah Vihear); the unlawful acquisition involving corruption (a crime then punishable under English law); the perfunctory title vetting; and the demand for their return from the US Senate and a majority of UN General Assembly members. Titi describes the intransigence of the UK government, which calls this a private matter for the trustees of the British Museum, identified as a non-departmental public body (NDPB), albeit receiving most of its funding from the government. A letter (dated Sept 2021) from the then Culture Secretary, Oliver Dowden, to government-funded museums expected their approach to contested heritage “to be consistent with the government’s position”, given the receipt of taxpayer support and the forthcoming Comprehensive Spending Review.

There is nothing like the regimented examinations of one trained in law. Titi lays out the history of Elgin’s activities, his late objective to improve the arts in Britain (by means of a sale), the possible remedies, and the inadequacies of international laws. Her thorough recital of returned patrimony includes objects from NDPB museums made possible by national laws that will be soon fortified by the enactment of the Charities Act, which would boost the possibility of a successful return in the case of the Parthenon Marbles.

• William St Clair, Who Saved the Parthenon? A New History of the Acropolis Before, During and After the Greek Revolution, Open Book Publishers, 898pp, 195 illustrations, £50.95 (hb) and £40.95 (pb) published 12 May 2022

• Catharine Titi, with a foreword by Andrew Wallace-Hadrill, The Parthenon Marbles and International Law, Springer, 329pp, £111.50 (eb) and £139.99 (hb), published 25 May 2023

• Eleni Vassilika was the keeper of antiquities at the Fitzwilliam Museum; the director and chief executive of the Roemer-und Pelizaeus-Museum; the director of the Museo Egizio di Torino; and the curatorial director at both the National Trust and the Zayed National Museum

See further articles on William St Clair and the Parthenon Marbles

See further coverage relating to the Parthenon Marbles