[ad_1]

By CARLEY PETESCH, Associated Press

KINSHASA, Congo (AP) — Congo’s President Joseph Kabila is stepping down after this month’s election but he doesn’t rule out seeking the post again in the future.

In a rare interview with The Associated Press, the Congolese leader, who ended months of speculation earlier this year by announcing he would not run again this time, said he doesn’t know what retiring from politics means. He took power in 2001 after the assassination of his father, Laurent Kabila, and says there is still more to be done in this mineral-rich but “complicated nation.”

“Well, I am not going to rule out anything in life,” Joseph Kabila, relaxed and smiling, said. “As long as you are alive and you have ideas as strong as you have, a vision, you should never rule out anything.”

That kind of talk has worried Congo’s opposition, which fears that Kabila will rule from the shadows if his preferred successor, ruling party candidate and former interior minister Emmanuel Ramazani Shadary, wins in the long-delayed Dec. 23 election.

The 47-year-old Kabila dismissed those concerns, saying the constitution makes it clear that such an arrangement is not possible. Yet he now acts as moral authority for a recently created political coalition, the Common Front for Congo, keeping himself close to power.

Kabila is eligible to run again for president in 2023, as Congo’s constitution merely rules out three successive mandates. For now, he said he will likely remain in the role of adviser: “If anyone wants advice from me, I hope they come and ask.”

Congo now faces what could be its first democratic, peaceful transfer of power since independence from Belgium in 1960, after a troubled history marked by Mobutu Sese Seko’s more than three-decade rule. At stake is a vast country blessed with trillions of dollars in natural resources but long destabilized by dozens of rebel groups.

Now an Ebola outbreak, the second-largest in history, poses a new threat to the election, whose delay since late 2016 led to sometimes deadly protests over Kabila’s long stay beyond his mandate. The government blamed the delays on difficulties in organizing the vote as a new wave of rebel fighting raged.

Critics of the delay “should be humble enough to realize that the Congo itself is a challenge and that the electoral process is a much bigger challenge,” Kabila said. Any country, be it the United States or France, would prioritize security over elections, he added.

Annoyed by the pressure at home and from abroad — including European Union sanctions on Shadary for obstructing Congo’s electoral process and a crackdown against protesters — Kabila and his administration have pushed back at so-called interference in Congo’s affairs and vowed to fund this election alone, with no outside money.

Kabila called the sanctions against Shadary “unjust and illegal.” EU officials have confirmed the sanctions will be prolonged this week.

Shadary or whoever is elected “will be the president of this country and not the president of Europe. God forbid,” Kabila said, laughing. Engagement with Europe will continue regardless, “so that one day they come to see the light because they are in darkness, completely in darkness. Or should I say they’re in a state of denial.”

In an ambitious but worrying move for many, Congo also is using voting machines for the first time, leading to questions from technical experts, diplomats and rights groups about how this infrastructure-starved country of 40 million voters, many without computer experience, will succeed.

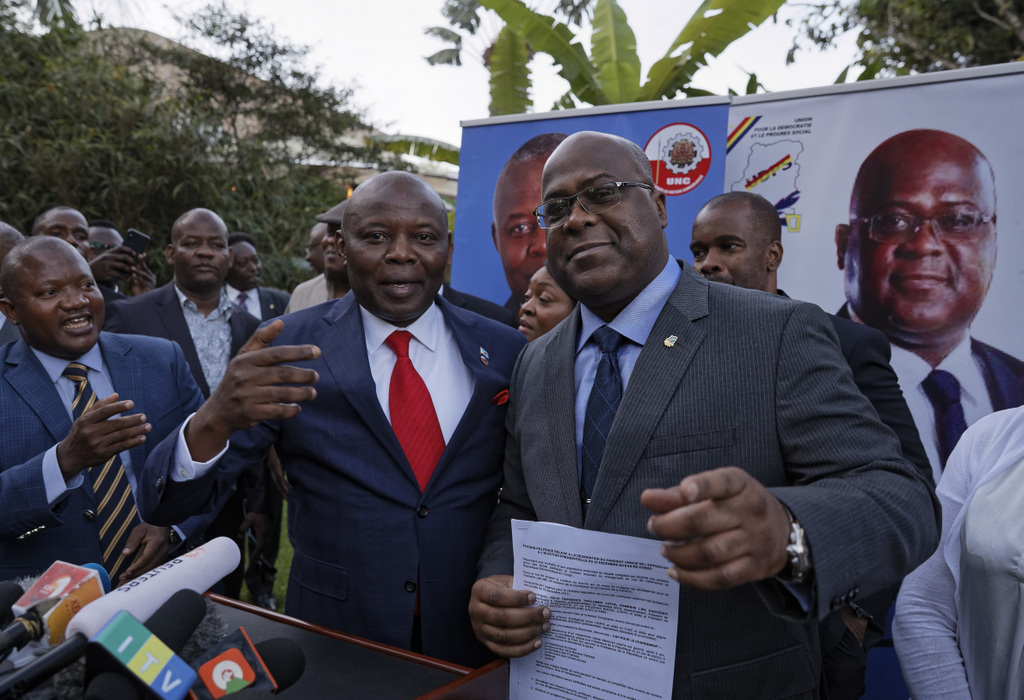

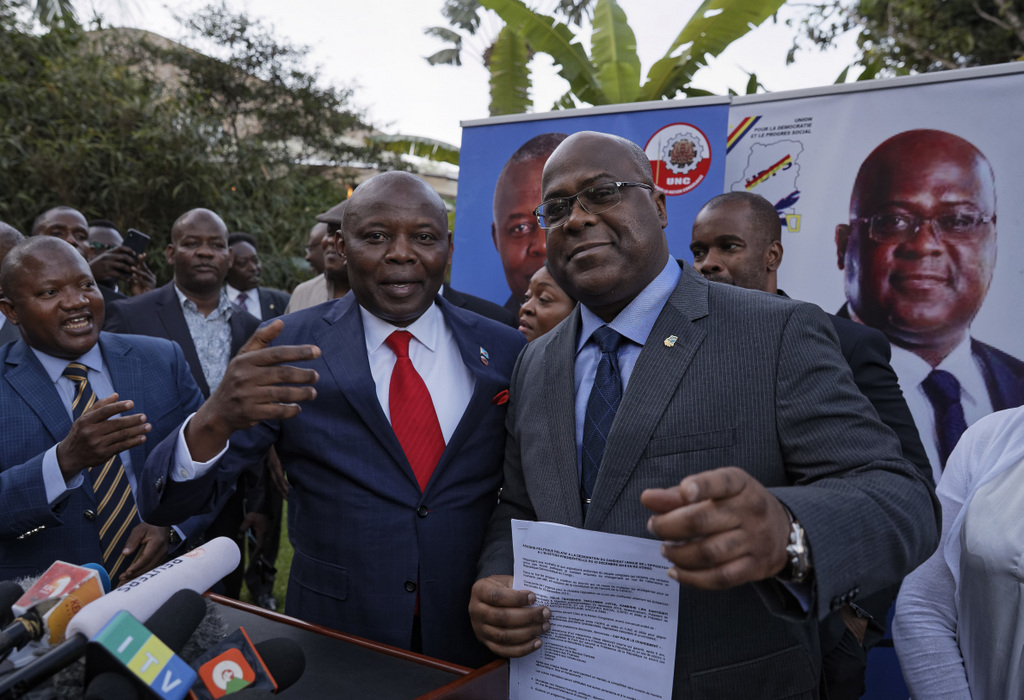

Congo’s two leading opposition parties have joined forces after withdrawing from a wider pact to support a single contender. Felix Tshisekedi with the country’s most prominent opposition party is representing his party as well as that of Vital Kamerhe. Martin Fayulu Madidi is the other leading opposition candidate.

Many in Congo worry that a divided opposition will hurt the chances of defeating Shadary in a single-round election. Congo has no runoff vote.

Fayulu rejected the idea that the constitution allows for Kabila to run again.

“I have the impression that he does not know the constitution well,” he told the AP. “The mandate of the president of the republic is five years, renewable once.”

Kabila defended his legacy, pointing to his past election wins, and said he wouldn’t miss the office when he leaves. “We’ve made lots of strides,” he said, noting that Congo’s budget was $250 million when he first took office and is $5 billion today. He himself has amassed vast wealth while in office.

He said he has done “the best that we definitely could” for Congo’s benefit since taking office.

The country’s long insecurity has hurt efforts to do more, he said: “Peace was elusive until a given period of time.”

Kabila sounded pensive about the future, whatever his role. “The work in this country will never be over,” he said. “The Congo is a country of a thousand challenges.”

___

Associated Press writer Saleh Mwanamilongo in Kinshasa contributed.

___

Follow Carley Petesch at https://twitter.com/carleypetesch and Africa news at https://twitter.com/AP_Africa

[ad_2]

Source link