[ad_1]

Last year, we sat down with our friend Clint Smith, renowned poet and writer whose TED talk, “How to Raise a Black Son in America” is reaching millions of folks.

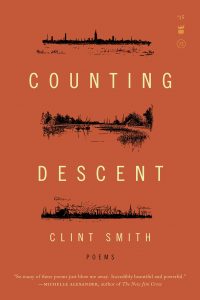

Smith recently published his first book, Counting Descent, and we got the chance to ask him a few questions. Pre-order the book here.

In May, you became a Cave Canem fellow, which is a big deal for black poets. You’re also a National Science Foundation fellow. Two awards from two seemingly different worlds. How do you make sense of juggling all these hats? Academic, poet, journalist, teacher.

If you study the black literary tradition, you see endless examples of people whose work existed across mediums, genres, and spaces. Du Bois who was a novelist and sociologist. Audre Lorde was a poet and essayist. Carter G. Woodson was historian and journalist . The common thread is that all of them were committed to using a range of intellectual projects to push forward their larger political project — the freedom of black people. So, for me, it doesn’t feel unnatural to be both a social scientist and an artist. In many ways, I’m simply following the lead of those who showed me it was possible.

Speaking of great black scholars, Michelle Alexander said of your book, “So many of these poems just blow me away” and called it “incredibly powerful and beautiful.” How did it feel to have a scholar like her praise your book in that way?

I still can’t believe it. The New Jim Crow was such an important book for me and to have her think so highly of my work means the world.

Last year, we produced a video on you where we asked, “what’s the responsibility of the black artist?” How has your thinking evolved on this amid everything that has happened since?

Nina Simone once said, “An artist’s duty, as far as I’m concerned, is to reflect the times.” I think that’s right. Great art tends to reflect the sociopolitical moment in which it was conceived. As of late, I’ve come to more fully appreciate that the black experience is profoundly diverse — we have different experiences and ways of seeing the world. So when we talk about the black artist’s responsibility, I think it’s important that we not impute a singular definition of responsibility onto a group of people who might have different notions of to whom their responsibility belongs.

So is your book a response to the current movement(s) we’re seeing in America?

I would say so. Like so many of us, I’ve been deeply impacted by all that has transpired over the past few years with regard to the state-sanctioned violence against black people. The book is largely wrestling with the cognitive dissonance of what it means to come from a family that celebrates you and existing in a broader world that often dehumanizes you. The book attempts to hold both of those things at once. Black joy. Black pain. The feeling of watching your parents dance to Maze & Frankie Beverly and the feeling of watching someone who looks like you being killed by police. Both of them are part of our lived experience. Both of them are stories I try to tell.

Over the last two years, your platform has grown tremendously, and you’ve touched on so many issues that are important to the black community. How do you select the subjects you address?

I spend much of my time studying the history of racial inequality in America. So a great deal of what I’ve been attempting to do in my research, art, and journalism are to put what is happening around us in historical context. I’m fortunate to have platforms that mean my ideas are going to be seen by a wide range of people — something I don’t take for granted — and my sense is that people are yearning for that context to explain some of what they’re seeing in the world today.

Which black writer has influenced your writing the most, and why?

I spent last semester reading all of the major works of Du Bois and that was transformative for me. Like I mentioned before, the way he moves across mediums — sociologist, historian, essayist, poet, novelist, journalist, teacher, activist — was something I found incredibly compelling. I also deeply appreciate the way that he allowed his ideas and positions to evolve over time, to admit when he got something wrong and to try and make it right so that his community would be better served by his work. He was tireless in his pursuit of justice and brilliant in how he communicated what justice might look like.

In ten words, how does it feel to publish your first book?

Thanks for taking me to the library growing up, Mom.

On a day to day basis, give us two ways you PushBlack.

Question everything, and remember that nothing about what our communities look like is an accident. It was built this way.

Order Counting Descent here.

Clint Smith is a doctoral candidate at Harvard University and has received fellowships from Cave Canem, the Callaloo Creative Writing Workshop, and the National Science Foundation. He is a 2014 National Poetry Slam champion and was a speaker at the 2015 TED Conference. His writing has been published or is forthcoming in The New Yorker, American Poetry Review, The Guardian, Boston Review, Harvard Educational Review and elsewhere. He is the author of Counting Descent (2016) and was born and raised in New Orleans.

[ad_2]

Source link