[ad_1]

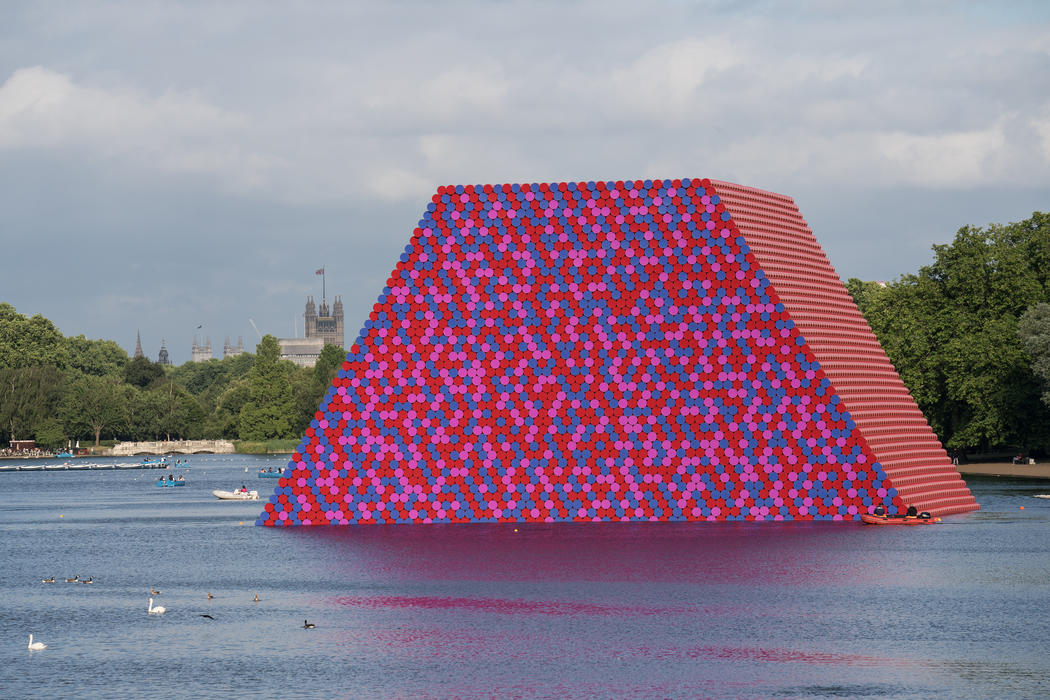

Christo and Jeanne-Claude, The London Mastaba, 2018.

©2018 CHRISTO/WOLFGANG VOLZ

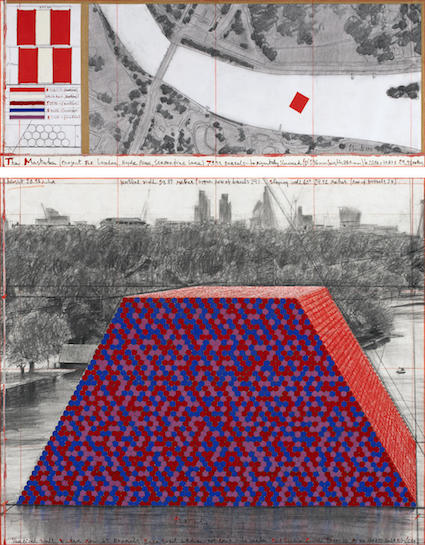

There is something quietly miraculous about The London Mastaba, Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s 600-ton pyramid-like form that glows red-orange and seemingly sprouts out of its own watery reflections in London’s Serpentine Lake. London is full of verticals, but the glistening structure (on view through September 23) is a matter of horizontals. Rows of 55-gallon barrels laid end to end comprise 90-foot-long flanks sloping at a 60-degree angle, each cylindrical container colored with identical bands of red and white. The rows are minutely off-kilter; the alternating bands that result create a kind of Op Art shimmer.

One recent day, at the invitation of the philanthropist Michael Bloomberg, I boarded a boat intended to allow Christo to get a closer view of his sculpture in advance of an inaugural press conference. Our craft rounded the structure’s corner and another surface appeared. From a distance, the plane’s elements resemble gumball-shaped circles of reds, blues, and purples. But now, as we passed, facets of the sculpture caught light under cloudy skies, creating a magically shifting radiance. Christo was wearing a cargo jacket with pockets, his white hair blowing in the breeze. He could be seen chatting with Bloomberg and Royal Parks chairman Lloyd Grossman; a group of chunky bodyguards with earpieces, their eyes darting here and there, accompanied them. “It’s a dream come true,” Christo said of the piece, “ever since Lake Michigan.”

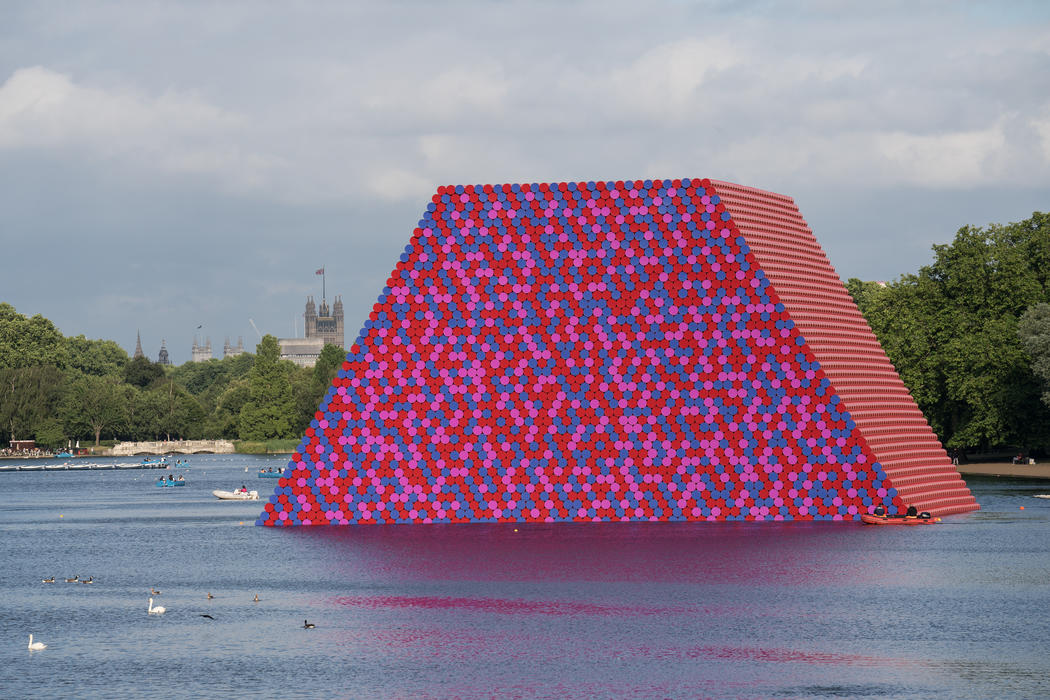

Christo, The Mastaba (Project for London, Hyde Park, Serpentine Lake), 2018, collage in two parts, pencil, charcoal, enamel paint, hand-drawn technical data, map and tape.

©2018 CHRISTO/ANDRÉ GROSSMAN

Christo and Jeanne Claude’s work has always been about defying the odds. In 1983, the couple surrounded entire islands off the coast of Miami with floating pink woven fabric, and in 1976, they boldly—and illegally—erected 46 miles of Running Fence in Northern California. Christo’s remark about Lake Michigan refers to an early 1968 idea that would have set a configuration of oil drums afloat in that body of water. It is one of 47 massive installation concepts by Christo and Jeanne-Claude still unrealized. (Twenty-three have been made a reality.) Such site-specific extravaganzas entail permits, environmental reports, and heroic haggling with civic officials; they often take decades to realize.

The London Mastaba took a mere two years to produce (the blink of an eye in Christo-time), the relative speed perhaps due to the connections of its Serpentine Gallery sponsor. Yet, maybe it needed more gestation time (more on that in a bit). Mentioned only in passing in press materials is that a “mastaba” more commonly refers to a Middle East memorial structure—a tomb, a “house of eternity.” Was it a coincidence that it’s only the second site-specific work Christo has realized since the death of his partner Jeanne-Claude in 2009? (The artist is adamant that “mastaba” refers to the work’s bench form alone, with its classic proportions of 2:3:4.) The work, as well as other projects by the pair, is completely self-funded, through the sale of artworks. “I am not at the mercy of foundations,” Christo observed. The Mastaba’s barrels are custom-made and recyclable. He has pledged to put money toward helping the lake’s ecosystem once the work is removed.

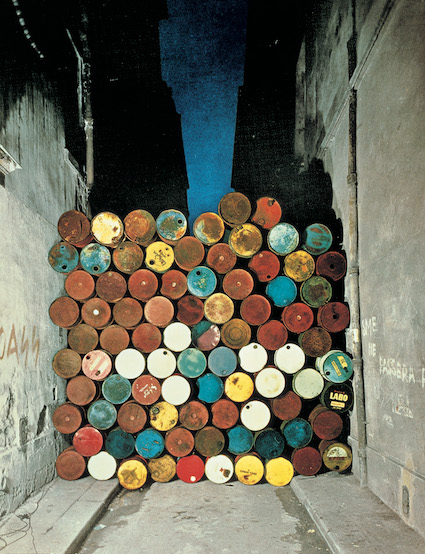

The London piece is a scaled-down version of Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s Abu Dhabi Mustaba, which has been in the works since the artists visited in 1979. Were it to be completed, it would be the world’s largest public artwork, and it’s been proposed for a desert in the United Arab Emirates, where the oil-barrel theme seems more suitable. But London and oil drums? Perhaps anticipating that very question, nearby the Hyde Park lake, a thoughtfully curated 80-object Serpentine Gallery exhibition spanning six decades points out that such containers have been a formative element in the artists’ output. And this has been the case since even before their first collaboration, a 1961 guerrilla action of stacked and wrapped oil cans and packages placed on a Cologne pier. Among other works, the two have proposed erecting an oil-drum facade in front of the Museum of Modern Art in New York. In 1962, they created a “Berlin Wall” of barrels blocking a Paris street. Sometimes, the work hints at a commentary on petroleum profits; other times, it may refer to art’s beloved medium of oil paint, or even to the notion of liquid energy as a kind of life force.

Christo and Jeanne-Claude, Wall of Barrels – The Iron Curtain, Rue Visconti, Paris, 1961–62.

©1962 CHRISTO/JEAN-DOMINIQUE LAJOUX/COURTESY THE ARTIST

The day I visited The London Mastaba, Hans Ulrich Obrist, the Serpentine’s artistic director, was on the boat, too. On our way over to the press conference, he discussed other ways that the barrel motif’s significance changes in different contexts. “For example,” he said, “I was just at the Musée d’Orsay looking at a Seurat.” In a flash, I saw his point. The colored barrel tops on each end form a pixelated surface, one that’s astonishingly like the Pointillism of the French Post-Impressionist’s painting A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of the Grande Jatte (1884–86), with its not-dissimilar blues, mauves, and red-pinks.

Yet, despite the pharaonic structure’s dazzle, there is something strangely inert about London Mastaba. Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s last two projects were gloriously participatory. For two weeks in 2005, awestruck New Yorkers meandered among saffron banners in Central Park as part of the project The Gates. In 2016, for Floating Piers, visitors flocked to Italy’s Lake Iseo to stroll on yellow fabric walkways. In contrast, the London Mastaba can be contemplated from the shore, more in the manner one would regard a traditional sculpture.

Obrist explained that Christo (who still discusses the projects using the pronoun “we,” as if Jeanne-Claude were still alive) had just turned 83. His late wife, the Morocco-born stepdaughter of a general, was known for her fiery red hair and equally determined mien. She began to receive full equal billing in 1994. Jeanne-Claude used to observe proudly, as proof of the destiny of their partnership, that she and Christo had been born on the same day and year. Her presence has not been forgotten.

Christo seemed in his element before a crush of video cameras, microphones on booms, and scribbling reporters as he explained that the piece is more than an artwork per se—it’s engaged with the weather, the water, its surroundings.

For many years, Christo and Jeanne-Claude had the reputation in the serious art world for being superficial publicity seekers, with their traffic-stopping “wrappings” of Paris’s Pont Neuf bridge in 1984 and the Berlin Reichstag in 1995. Yet gradually, the ingenuity of their Surrealist juxtapositions, the breathtaking play of differences in scale (for example, the intimate act of package-wrapping combined with a huge monument), and the sheer heroism of their efforts began to win over even academic scholars. And in today’s art world, dominated by artist-businessmen like Damien Hirst or Jeff Koons, Christo seems a veritable ascetic.

“My building in New York,” he said, “doesn’t have an elevator—I walk up the stairs, I don’t drive, I don’t like to talk on the phone. This is not TV. This is the real world. The art world has become the virtual world. I like to live in the present.”

[ad_2]

Source link