[ad_1]

Christo died in New York on May 31, eleven years after the passing of Jeanne-Claude, his artistic collaborator and life partner. In Christo’s last days, activists filled the streets demanding justice for the African Americans killed by police and an end to systemic racism. Protesters have since then defaced and destroyed monuments to white supremacists and imperialists as powerful currents of resistance remake the public sphere—a fact not tangential to the career of Christo and Jeanne-Claude, forged by political upheaval. Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s epic projects provoked debates about power and agency in public space, none more famously than their Wrapped Reichstag (Berlin, 1971–95).¹ “It’s not illustration of politics, it’s real politics; real debate in the parliament [over whether to permit the German parliament’s wrapping],” Christo explained in a recent interview.

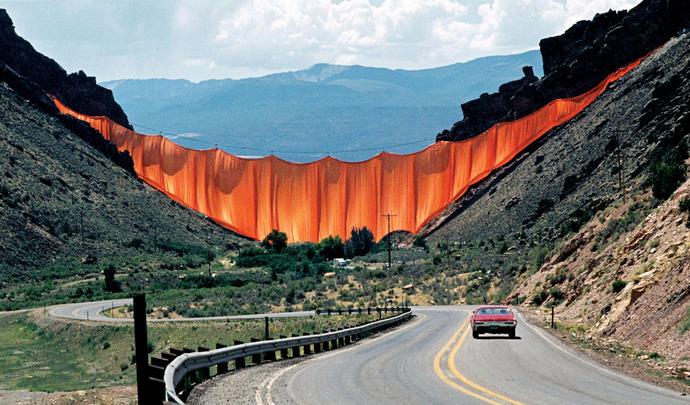

Though Christo and Jeanne-Claude often worked in the environment, their practice embodied not the geological scale of Land art, but the glacial pace of bureaucracy and the legislative process. By this measure, they were enormously productive, able to complete more than twenty large-scale environmental projects since the late 1960s. The artists negotiated with community groups, city councils, and federal agencies. Their vibrant, billowing fabric installations were the fruits of arduous labor performed over decades: acquiring permits and approvals, conducting environmental studies, settling lawsuits, and, finally, managing contractors and construction crews. Some of this labor is chronicled in the 1978 film Running Fence, which follows the artists through several years of public hearings and meetings with community groups that preceded the two-week lifespan of the twenty-five-mile fence. A tone of somber exhaustion pervades the project descriptions on their website: Wrapped Reichstag, extant for two weeks in June 1995, represented “24 years of efforts in the lives of the artists.” Valley Curtain (1970–72), a 1,250-foot-wide piece of fabric suspended between mountain slopes near Rifle, Colorado, took twenty-eight months to complete, but “28 hours after completion of the Valley Curtain, a gale estimated in excess of 60 mph . . . made it necessary to start the removal.” And many projects conceived and designed never achieved even fleeting physical form.

© Christo. Photo André Grossmann.

As the era of Christo and Jeanne-Claude draws to a close, the artists leave a legacy of projects anchored to time and place and predicated on brevity—or not realized at all. The “Projects Not Realized” category of their website is a substantial catalogue in itself. However, to Christo and Jeanne-Claude, “Projects Not Realized” were only plans, not yet artworks. The artists eschewed conceptualism. “A conception on a paper is not Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s idea of art . . . The only way to see it is to build it,” they wrote. Matthias Koddenberg, a spokesperson for the artists, indicated to me that it was not their intent for unrealized projects to be completed posthumously. “Christo’s drawings show the evolution and crystallization of the projects. For most of the non-realized projects, the final decisions were never made. Thus, they could not be realized according to the artists’ vision.” Only two unrealized projects had reached the stage of final approval, blueprints resolved, allowing their posthumous completion. L’Arc de Triomphe, Wrapped, first proposed in 1962, is scheduled to be realized for three weeks in the fall of 2021, in collaboration with the Centre des Monuments Nationaux and the Centre Pompidou. Delayed due to the COVID-19 outbreak, this project was originally intended to coincide with the exhibition “Christo and Jeanne-Claude. Paris!,” scheduled to open at the Pompidou in July, and focusing on the period from 1958 to 1964, when the pair lived in Paris and conceived L’Arc de Triomphe, Wrapped and Le Pont-Neuf Wrapped (1975–85), as well as numerous smaller-scale projects.

© Christo. Photo André Grossmann.

The other finalized project, The Mastaba, was developed in 1977 for Abu Dhabi. Despite extensive planning, including engineering and economic impact studies and scale-model tests, no completion date has been announced. The 492-foot monument, if and when it is realized in physical form, would be the artists’ only permanent large-scale work. Described on their website as “the largest sculpture in the world, made from 410,000 multicolored barrels to form a mosaic of bright sparkling colors, echoing Islamic architecture,” The Mastaba would culminate a series of oil-barrel sculptures and environments. Earlier works were overtly political: Wall of Barrels—The Iron Curtain (1962) offered aesthetic parallels to both the Berlin Wall and the barricades activists erected around Paris in response to the Algerian War. The artwork was a disruptive action: Christo and Jeanne-Claude stacked used, rusted oil barrels in the narrow Rue Visconti, blocking the Paris street for eight hours. In oil-rich Abu Dhabi, The Mastaba, in its extreme scale, would memorialize a petro-dependent civilization and the Anthropocene era.

Many “Projects Not Realized” are powerful concepts developed over years, and it is worth considering what might have been had the vagaries of bureaucracy or community played out differently. In the 1960s and 1970s, the artists proposed wrapping monuments, from Picasso’s Bust of Sylvette on the New York University campus to Geneva’s Reformation Wall. Most poignant is Wrapped Monument to Cristobal Colón (Project for Barcelona), proposed for the columnar monument in Barcelona that rises nearly two hundred feet at the edge of the Mediterranean. Columbus crowns the column, pointing toward the New World. Christo and Jeanne-Claude received a permit to execute this project in 1984, after two failed attempts and nine years after their original proposal. By then, the artists were pursuing environmental works like Surrounded Islands (1981–83) in Miami’s Biscayne Bay, and decided not to proceed. But the collaged drawings of the sheathed explorer are haunting, particularly in light of Confederate monuments shrouded in recent years, by both protesters and municipalities. Christo and Jeanne-Claude proposed an undoing, a cancellation, a reversal, suspending a world without the memorialized individual or event. What would the world be like without the enslavement and slaughter of colonial conquest?

Photo Wolfgang Volz.

The wrapped monuments invite projection, as do wrapped architectural edifices. The artists were reticent about the political implications of their work, focusing on formal, procedural, and material dimensions, even as they always chose to wrap “something profound” that would tap into deep cultural meanings. They were committed to building consensus over years and using legal channels to create public work. These channels sometimes failed or ended in defeat, and the artists were forced to walk away. However, these failures themselves became stories, visualized and narrated as “Projects Not Realized.” Activists today bringing down emblems of white supremacy with their own hands after legal channels and moral arguments have failed offer an important distinction: this is life, not art, and accepting defeat is no longer an option.

In 2017, Christo ended Over the River, Project for the Arkansas River, State of Colorado twenty-five years after it was first proposed in 1992. The project, on federal land, was approved by the Bureau of Land Management after review of an Environmental Impact Statement (required for infrastructure projects like highways and dams, this was the first ever for an artwork, according to Christo). Yet a group called ROAR—Rags Over the Arkansas River—filed lawsuits, concerned about impacts on local people and wildlife. Ultimately, Christo attributed his withdrawal to the election of Donald Trump. “I use my own money and my own work and my own plans because I like to be totally free,” he told the New York Times. “And here now, the federal government is our landlord. They own the land. I can’t do a project that benefits this landlord.” Translucent, shimmering fabric panels suspended at intervals over a forty-two-mile stretch of the Arkansas River are never to be. Exaggerating the river’s luminosity and highlighting the dramatic geological formations of the river valley and surrounding mountains, the project would have brought an influx of tourism and new perceptual experiences of the landscape. Even unrealized, Over the River illuminates the way that landscape is affected by political discourse, both local and global.

© Christo + Wolfgang Volz. Photo Wolfgang Volz.

Major projects by contemporary artists such as Postcommodity’s Repellent Fence (2015) or Mary Mattingly’s Swale (2016–) are indebted to Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s patient model of durational engagement, problem solving, and embrace of legal and legislative processes as a tool for art-making. The social goals are more explicit in these instances: Mattingly pursues legislation to allow produce to be grown in urban food deserts. Postcommodity’s project is a symbolic undoing of borders through a temporary “fence” of scare-eye balloons crossing from Douglas, Arizona, to Agua Prieta, Sonora, in recognition of Indigenous lands (their process is documented in the excellent film, Through the Repellent Fence [2017]). By contrast, Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s projects were, in Christo’s words, “totally irrational, totally useless. Nobody needs them. The world can live without them.” In their useless irrationality, the dogged, decades-long engagements of Christo and Jeanne-Claude broke ground for a new art.

¹ Though most of Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s large-scale projects existed for brief periods, the works are typically dated to reflect the process from initial conception to final realization.

[ad_2]

Source link