[ad_1]

Installation view of “Charline von Heyl: Snake Eyes, 2018–19, at Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, D.C.

CATHY CARVER/COURTESY THE ARTIST

Charline von Heyl’s career has experienced some dramatic ups and downs over the past year. A solo show of her latest paintings made a big splash when it opened the New York art season last September. The effusive critical notices attracted crowds to Petzel gallery in Chelsea. Two months later, “Snake Eyes,” a survey of 36 works by von Heyl from 2005 to the present, debuted at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in Washington, D.C. However, when the federal government shut down, the show got caught in the crosshairs. With the closing date for the exhibition looming, it looked as if many people wouldn’t get the chance to see the work on view, which had been lauded by many reviewers. But, wonderfully, when the Hirshhorn reopened along with other local institutions, its leadership extended it through April 21.

“Snake Eyes” is a compelling exhibition by an intriguing painter. German-born and New York–based, von Heyl, 59, executes work that deserves to be experienced in depth. It’s easy enough to admire one of her canvases or collages at an art fair, but by not seeing lots of them in one venue, you miss the opportunity to be dumbfounded by the variety of ways she solves aesthetic problems.

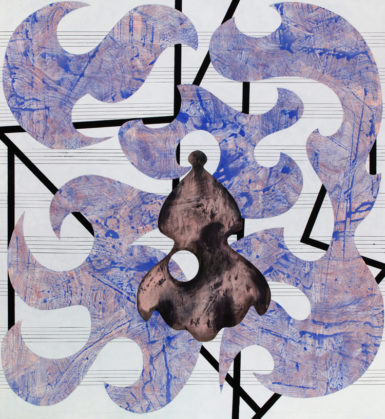

Charline von Heyl, Lady Moth, 2016–17, acrylic and charcoal on linen, 86 x 82 inches.

©CHARLINE VON HEYL/COURTESY THE ARTIST AND PETZEL, NEW YORK

For many years, von Heyl has been upending long-held notions about abstract art. For starters, she peppers many of her paintings with representational imagery, a throwback to the days of Synthetic Cubism some 100 years ago. And, situating her canvases very much in the moment, she also adds fragments of poetry, though these textural bits are mostly indecipherable. And she hardly ever works in series. When she does, it’s like a New York Knicks winning streak: just two or three in a row.

Chronological progression does not interest von Heyl, and “Snake Eyes” offers no trace of how one canvas might lead to another. “I’m not interested in linear development,” she told me over the telephone last December from the studio she maintains in Marfa, Texas. The galleries are organized by mood rather than date. “Every room has a different mood,” the artist points out in a short video on the Hirshhorn’s website. “Some are very uplifting,” while in another “there is a dark undertone.” Put another way, she views installations “almost as if they’re a game of chess in three-dimensions.”

“Every room,” she has said, “should have its own rhythm, atmosphere, power.”

At a time when some still associate abstract art with a proverbial Joseph’s coat of colors—pace Stella, Louis, and Frankenthaler—von Heyl often expresses herself with a range of blacks and other dark hues. On occasion, rather than oils or acrylics, she uses interference pigments, which were only released about 20 years ago and which alter your perceptions of color right in front as you walk from one end of a canvas to another. Black, for example, can become blue in a matter of seconds.

Installation view of “Charline von Heyl: Snake Eyes, 2018–19, at Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, D.C.

CATHY CARVER/COURTESY THE ARTIST

Complicating all of these properties and elements even further is the manner in which the painter combines what she learned as an art student and fledgling artist in Germany during the 1980s with the practices of what she has absorbed in the United States since moving here in 1996. Check out her canvases from around two decades ago. They’re softer and less dynamic than her subsequent work. There’s very much a before and after in her oeuvre.

Von Heyl has taken an unlikely path to the pinnacle of contemporary abstraction. Born in Mainz in 1960, she was raised in Bonn. Her dad was a lawyer; her mom, a psychologist. In Hamburg, she studied art with Jörg Immendorf; and in Düsseldorf, with Fritz Schwegler, who is not a household name in American art circles. “Abstraction,” she has said, “was absolutely nonexistent in my immediate surroundings in Germany in the ’80s.”

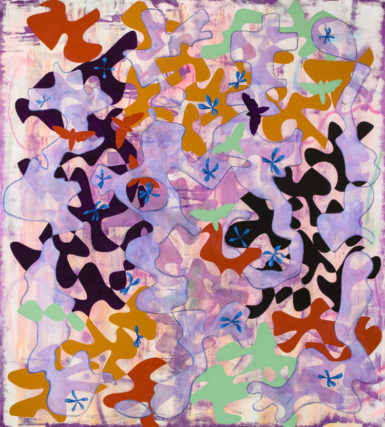

Charline von Heyl, Nunez, 2017, acrylic, oil and charcoal on linen, 82 x 78 inches.

©CHARLINE VON HEYL/COURTESY THE ARTIST, GALERIE GISELA CAPITAIN, COLOGNE, AND PETZEL, NEW YORK

During the late 1980s and early ’90s, she was around artists who are lionized these days: Martin Kippenberger, Sigmar Polke, Albert Oehlan, and Immendorf. The German art scene was, as she’s put it, “heavily male, very jokey, with an ironic stance toward painting. Anarchistic and also quite arrogant.” As an antidote to Neo-Expressionism, there “was irony, mostly in the form of really stupid jokes.”

“I liked the work, I liked the guys,” she has recalled, “but it wasn’t something that I could, or wanted to, do.”

When von Heyl had the opportunity to come to New York for a solo show at Petzel, she took a big leap and moved here. Soon after, she had a reason to stay for good. She married painter Christopher Wool.

When von Heyl’s wildly diverse paintings are brought together, it’s a bit surprising that they don’t cancel each other out or engender a cacophonous din. After all, they feature clashing patterns, lots of details, and off-beat colors. However, they also have many sections where she’s applied white pigments or left the canvas raw. This has a calming effect, along with the omnipresent blacks.

Her attitude toward space is unusual as well. Though her works are decidedly flat, she sees her art as sculptural. She wants the forms in her paintings to project outward toward their viewers. This is not quite the same as Hans Hofmann’s notions regarding push/pull because von Heyl doesn’t want to depict deep space. She’s trying to activate the area between the painting and its viewer. Because “something happens,” she has noted, “you’re in the moment.” As she works, she has other aims, too. She has said, it’s “always about making a painting more alive.”

Installation view of “Charline von Heyl: Snake Eyes, 2018–19, at Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, D.C.

CATHY CARVER/COURTESY THE ARTIST

At the Hirshhorn, you find innumerable panels that feel composed with billowing or floating imagery. Take a look at The Language of the Underworld (2017), which is a complicated visual feast. It’s easy to get lost in its waves of abstract forms, but the heads she has embedded amid them ground you. At the same time, the difficult-to-read text may puzzle you, and you might be reminded of some of Laura Owens’s more recent paintings, which are similarly overloaded. These are the progeny of Frank Stella’s later works.

As for von Heyl’s palette, it’s more European than American, a remnant of where she began. Glance through von Heyl’s catalogues, and you’ll find lots of paintings, including end papers, executed with lavenders and daffodil yellows. Like Joan Mitchell, who bought her art supplies in France, the roots of her oeuvre are on the Continent.

Now look at the 36 paintings by von Heyl on view at the Hirshhorn. Take your time. They look as if they were executed quickly, but they weren’t, and you’ll find that going slowly is also the best way to intuitively understand every mark and gesture she’s made. You’ll better appreciate, too, von Heyl’s recent declaration that abstraction is “about imploding meaning.”

[ad_2]

Source link