[ad_1]

Cecil Taylor at the Whitney Museum in 2016.

COURTESY WHITNEY MUSEUM

In a jazz milieu that teems with uniqueness and idiosyncrasy, Cecil Taylor was especially idiosyncratic and unique. Each sounding of his piano, which often sounded like more than one piano, took up a position within his own self-created context and against pretty much all else, at least among the creations of his musical peers. When news spread last night of his death, at the age of 89, there was no escaping the sense that one of the last genuine giants of jazz’s most heady and contentious prime has gone.

Listening to Taylor in his element could—and should—be a jarring affair. The first time I saw him play—at New York’s Knitting Factory in the late 1990s, if memory serves, in a duet with another performer I can’t for the life of me recall—I was off-balance and more than a little confused. I remember feeling agitated, even though I had some listening proficiency with experimental free jazz. But I also remember that night marking a new beginning for a long and ongoing joust with thinking about and around improvisation as an art form in and of itself.

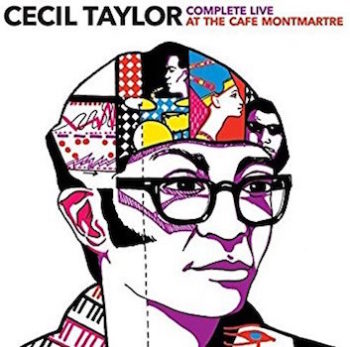

Listening to Taylor’s recordings—among my favorites are a collection of club dates from 1962 compiled as Complete Live at the Cafe Montmartre and the dense and formidable Unit Structures and Conquistador!, recorded within six months of each other in 1966—can be transporting. But seeing him in the flesh, in air that would warp and warble by way of what was coming from his piano, was the preferred mode. Followers in New York were lucky to get to do that at the Whitney Museum in 2016, when the institution’s soaring fifth floor was devoted to a survey of Taylor’s work. Curated by Jay Sanders, then at the Whitney and now the director of Artists Space, and Lawrence Kumpf, formerly of Issue Project Room and now the founder of the roaming performance platform Blank Forms, the exhibition was part of a multidisciplinary five-part “Open Plan” series that positioned Taylor among Michael Heizer, Andrea Fraser, Lucy Dodd, and Steve McQueen.

Listening to Taylor’s recordings—among my favorites are a collection of club dates from 1962 compiled as Complete Live at the Cafe Montmartre and the dense and formidable Unit Structures and Conquistador!, recorded within six months of each other in 1966—can be transporting. But seeing him in the flesh, in air that would warp and warble by way of what was coming from his piano, was the preferred mode. Followers in New York were lucky to get to do that at the Whitney Museum in 2016, when the institution’s soaring fifth floor was devoted to a survey of Taylor’s work. Curated by Jay Sanders, then at the Whitney and now the director of Artists Space, and Lawrence Kumpf, formerly of Issue Project Room and now the founder of the roaming performance platform Blank Forms, the exhibition was part of a multidisciplinary five-part “Open Plan” series that positioned Taylor among Michael Heizer, Andrea Fraser, Lucy Dodd, and Steve McQueen.

The exhibition was outfitted with archival video footage and documentation ranging from concert posters and poetry drafts to musical ephemera and alien notational scores. A highlight was an evening when Taylor himself took the stage built for him and lifted it up into space. Tickets were hard to come by, and there was a real fever in the room. The Whitney was then still very new and, for serious followers of music, the museum’s decision to devote so much space and solemnity to an artist of Taylor’s kind felt momentous.

I remember Taylor being walked slowly up to the stage, thin and frail but with a glow around him. (Was he wearing a fur coat? If not literally, figuratively he was.) Once at his piano, he played two sets: the first one skewedly lyrical and pared down, accompanied by the dancer Min Tanaka and drummer Tony Oxley, and the second one with a swelling band of free jazz fire-breathers and readings of poetic incantations. I remember talking to a not especially musically inclined curator afterward and hearing him express a sort of a submissive acquiescence to feelings of bafflement and confusion. It was perfect.

In a profile of the writer and theorist Fred Moten in the latest issue of ARTnews, a brief section revisits a group conversation involving Taylor and a cast of other artists in 1967: Arnold Rockman, Michael Snow, Harvey Cowan, Stu Broomer, Aldo Tambellini, and, most notably, Ad Reinhardt. As chronicled in Moten’s essay “The Case of Blackness,” the conversation circles around notions of blackness as more than just a color or non-color, as it were. Taylor speaks “in a kind of counterpoint to or with Reinhardt,” Moten writes, while tracking the tête-à-tête with a perceptive critical eye. It’s worth reading the whole essay for all it has to offer, but a few verbal riffs by Taylor stand out for what they say about the brain that authored them on the fly. One, on the notion of “black power,” goes like so:

Unfortunately, newspapers must sell, and I think they give a meaning of the moment to something which has long been in existence. The black artists have been in existence. Black— the black way of life—is an integral part of the American experience—the dance, for instance, the slop, Lindy hop, applejack, Watusi. Or the language, the spirit of the black in the language—“hip,” “Daddy,” “crazy,” and “what’s happening,” “dig.” These are manifestations of black energy, of black power, if you will. Politically speaking, I think the most dynamic force in American political life since the mid-1950s has been the black surge for equal representation, equal opportunities and it’s becoming an active ingredient in American life.

Another, on the subject of living with varied conceptions of the color black from vantages that differ, resonates all the more now that Taylor is no longer in the present tense. (It’s unclear what the quotation marks connote—maybe cited writing by Taylor himself?—but somehow the uncertainty suits.)

I think for my first statement I would like to say that the experience is two-fold and later, I think you’ll see how the two really merge as one experience.

“Whether its bare pale light, whitened eyes inside a lion’s belly, cancelled by justice, my wish to be a hued mystic myopic region if you will, least shadow at our discretion, to disappear, or as sovereign, albeit intuitive, sense my charity, to dip and grind, fair-haired, swathed, edged to the bottom each and every second, minute, month: existence riding a cloud of diminutive will, cautioned to waiting eye in step to wild, unceasing energy, growth equaling spirit, the knowing, of black dignity.”

Silence may be infinite or a beginning, an end, white noise, purity, classical ballet; the question of black, its inability to reflect yet to absorb, I think these are some of the complexes that we will have to get into.

[ad_2]

Source link