[ad_1]

Carlos Cruz-Diez.

©2019 CRUZ-DIEZ ART FOUNDATION

Carlos Cruz-Diez, the revered Venezuelan-born artist whose multilayered, eye-popping works challenged conventional notions of perception, color, and light, helping to define what became known as Kinetic Art and Op Art, died in Paris on Saturday at the age of 95. The news was confirmed in a post on his official website.

Cruz-Diez rose to international prominence in 1965 when he had work in the foundational exhibition “The Responsive Eye,” curated by William Seitz at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. The exhibition created a media frenzy at the time, as general-interest publications marveled at the dizzying and perspective-challenging effects of the abstract art on view.

The exhibition mostly included American and European artists, including Julian Stanczak, Victor Vasarely, Josef Albers, Larry Bell, Ellsworth Kelly, Robert Irwin, Agnes Martin, Bridget Riley, and Frank Stella, among many other well-known names. Cruz-Diez, whose 1964 Physichromie Number 116, made of plastic strips painted with tempera on cardboard, was his only work in the show, was among a small contingent of Latin American artists who had relocated to France and Germany included in the show.

Many art critics at the time disparaged the exhibition. Writing in ARTnews, Thomas B. Hess deemed it a “a mishmash” that “lumps together at least six totally different kinds of painting and sculpture.” Hess especially took issue with the “Hard-Core Op—shapes that provoke strong, often violent, ‘retinal’ illusions, such as after-images, sensations of motion, of blinking, pinging, popping, glowing. . . . Like the T.V. viewer, the Op audience passively participates, conditioned into giving up critical faculties, or at least suspending disbelief. Peripatetic zombies. The threshold of interest is very low; almost anything can be amusing.”

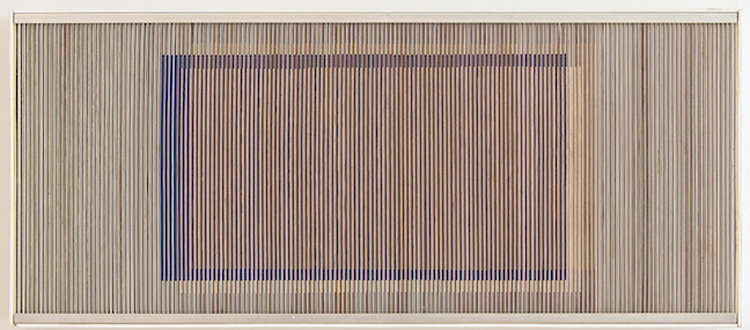

Carlos Cruz-Diez, Physichromie 216, 1966, Cardboard and aluminum modules with wood strip frame.

©2019 CARLOS CRUZ-DIES ADAGP, PARIS, AND DACS, LONDON/COURTESY SICARDI | AYERS | BACINO, HOUSTON

In a 2010 interview with Roger Atwood for ARTnews, Cruz-Diez provided what could be read as a subtle response to Hess’s criticisms of Op Art: “Painting bored me. So I started to do something else. What I tried to create is a dialectical relationship between the viewer and the work. When you’re in front of a Rembrandt, you see what Rembrandt created. With the kind of art that I [make], you see a situation—an instant. It constantly changes because light constantly changes.”

As the longtime editor of ARTnews from 1949 to 1972, Hess is perhaps most closely identified with his fierce support of Abstract Expressionism and the New York School. In the same ARTnews interview, Cruz-Diez said he and his lifelong friend from Caracas and fellow Op artist Jesús Rafael Soto dismissed the supposed superiority of Abstract Expressionism, seeing it as a dead end that was merely “painting as if you were playing the drums, like letting off steam.”

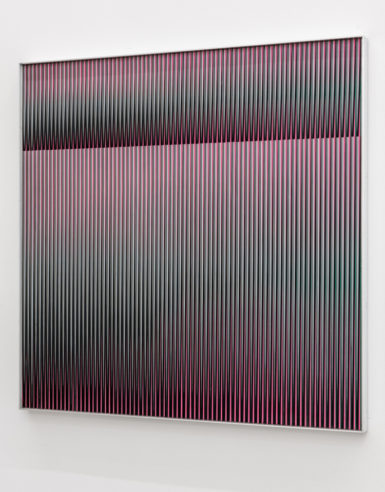

Carlos Cruz-Diez, Physichromie 888, 1974, aluminum, silkscreen, and stainless steel.

©2019 CARLOS CRUZ-DIES ADAGP, PARIS, AND DACS, LONDON/COURTESY SICARDI | AYERS | BACINO, HOUSTON

Carlos Cruz-Diez was born in Caracas, Venezuela, in 1923. He studied at the city’s Escuela de Artes Plásticas y Aplicadas from 1940 to 1945, where he met Soto and the artist Alejandro Otero. Together the trio would form “the holy trinity” of postwar Venezuelan art, as curator Gabriel Pérez-Barreiro said in 2010.

Indeed, art and architecture in Venezuela over the past half-century is deeply indebted to their pioneering Kinetic works, which rely on the movement of the art object or the viewer to create a full aesthetic experience, and Cruz-Diez produced numerous major site-specific commissions around the country, including at Caracas’s main international airport, as well as throughout the world. Among his best-known are the twisting sculpture, Fisicromía para Madrid, installed in Madrid’s Parque Juan Carlos I in 1991 and a walkway for the Marlins stadium in Miami in 2012.

After graduating from art school, Cruz-Diez first worked as an illustrator for various magazines and newspapers, and in 1946 became a creative director at the Venezuelan branch of the storied advertising agency McCann-Erickson. The following year, he traveled to New York for an advertising training course, and had his first solo show, of gouache drawings, in Caracas. In 1955, he moved to Barcelona for a year and a half, and during that time he visited Paris, where Soto had already relocated, and saw the landmark exhibition of Op Art at the Galerie Denise René during his visit.

“I didn’t know Soto was doing his own Kinetic work, or even that there was such a thing as Kineticism, until I arrived in Paris in 1955 and saw the exhibit at Denise René,” Cruz-Diez said in the 2010 interview. “That opened my eyes. Painting in Paris in those days was dead. I saw a huge room of paintings at the Salon de Mai and thought these must all have been painted by the same artist. They all looked the same. Abstraction had become the academy.”

Cruz-Diez returned to Caracas and began searching for a way to move art forward, away from such academic ideas, and in 1959, he had his breakthrough when he sketched a red line and a green line askew on a black background. Cruz-Diez had arrived at an optical illusion where somehow “a yellow that’s not there [appeared],” Pérez-Barreiro said. “And that’s the kernel of everything that follows.”

Installation view of “Carlos Cruz-Diez: Autonomía del Color,” 2017, at Sicardi | Ayers | Bacino, Houston.

COURTESY SICARDI | AYERS | BACINO, HOUSTON

Cruz-Diez moved to Paris the following year, in 1960, where he lived until his death. There he began to develop his rigorously conceived work, which was firmly grounded in his own version of theory of color and light. It was work that moved as the viewer moved, that shifted as she shifted—where what appeared was, in fact, not there.

He first created his works by adhering colored strips of plastic to cardboard, at small scale. In 1973, for archival purposes, he switched permanently to working with aluminum and as time went on, his work became more ambitious and grander in scale—whole walls could be become a place to experience how interactions of light and color were experienced in the eyes of viewer.

Just as Cruz-Diez’s work sought to challenge the ways in which a two-dimensional work could become three-dimensional, his work eventually leapt off the wall and into sculptures, installation, and immersive environments, what he called “Chromosaturations,” in which neon lights are projected into a space as a way to produce saturated hues in their purest form.

In an email, his longtime New York dealer Leon Tovar wrote, “In his approach to color and his desire to release color from the confines of form, he infused it with a poetry that allowed us to see the world with new eyes. Cruz-Diez’s artwork wasn’t limited to any gallery, to any museum, or even to art history—it gave us lessons to use in our everyday lives. As one of the last of the pioneering kinetic and optical artists, such a breakthrough is part of his enduring legacy.”

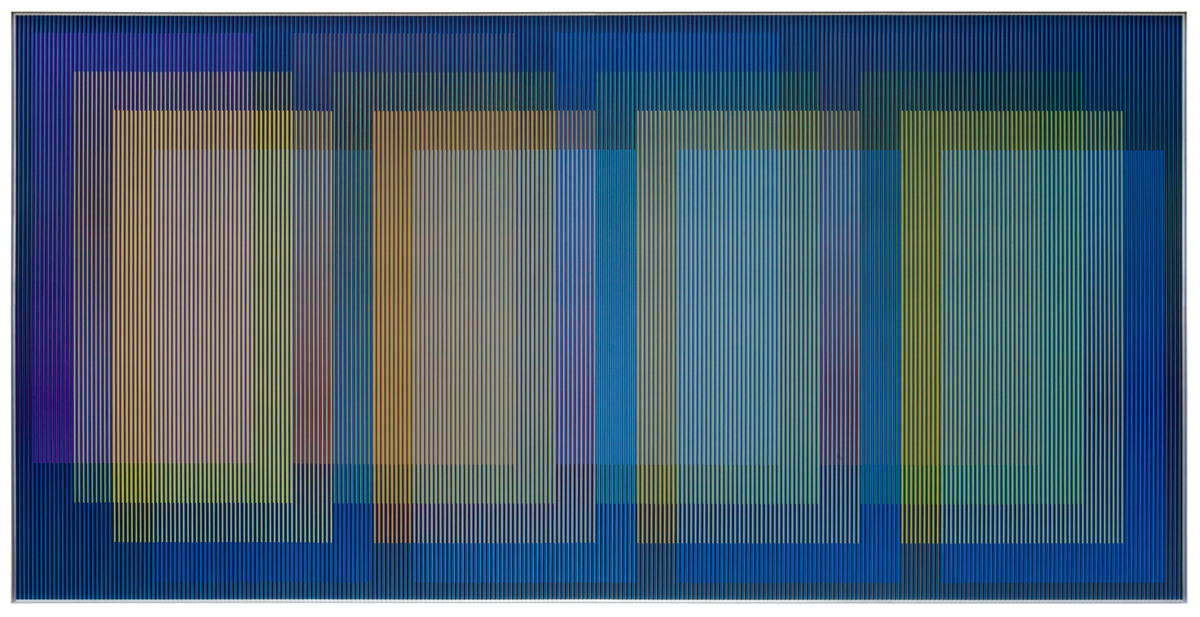

Carlos Cruz-Diez, Physichromie Panam 309, 2018, Chromography on aluminum.

©2019 CARLOS CRUZ-DIES ADAGP, PARIS, AND DACS, LONDON/COURTESY SICARDI | AYERS | BACINO, HOUSTON

In 1967, Cruz-Diez won the international painting prize at the 9th Bienal de São Paulo, and in 1970, the artist represented Venezuela at the Venice Biennale. A 2008 exhibition at the Americas Society in New York, titled “(In)formed by Color,” brought him renewed prominence. A career retrospective at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, curated by Mari Carmen Ramírez, that brought together 150 of his works followed in 2011.

“Carlos Cruz-Diez’s life was consumed with his passion for color and for communicating a novel chromatic experience to the world at-large,” Ramírez wrote in an email to ARTnews. “If there is an artist who came close to realizing his Utopian vision it was indeed Carlos. Despite the complex scientific and aesthetic theory that supported his production, his work was easily accessible to anyone who cared to experience it.”

While Cruz-Diez was lionized in Latin America and particularly Venezuela, he was less well known for most of his career in the United States and Europe, where Op Art became a marginal movement in the years after the 1965 MoMA exhibition. In 2016 exhibition, though, El Museo del Barrio staged an essential exhibition, “The Illusive Eye,” that handily rebutted the criticism of Hess and others, centering Latin American artists as being at the forefront of Op and Kinetic Art, as it simultaneously made the case that they are essential parts of 20th-century art history.

However, Cruz-Diez, ever the radical, would no doubt reject having his work merely consigned to history, and one can see his influence on many younger generations of artists, from Ad Minoliti to Sarah Sze to Tauba Auerbach, and many others. And his art, it has to be remembered, was about rejecting any notion of static identity or image. As he once put it: “There is a yellow here and a red there, but they are permanently in the process of becoming. They are never fixed. This work is not happening in the past. It is forever in the present.”

[ad_2]

Source link