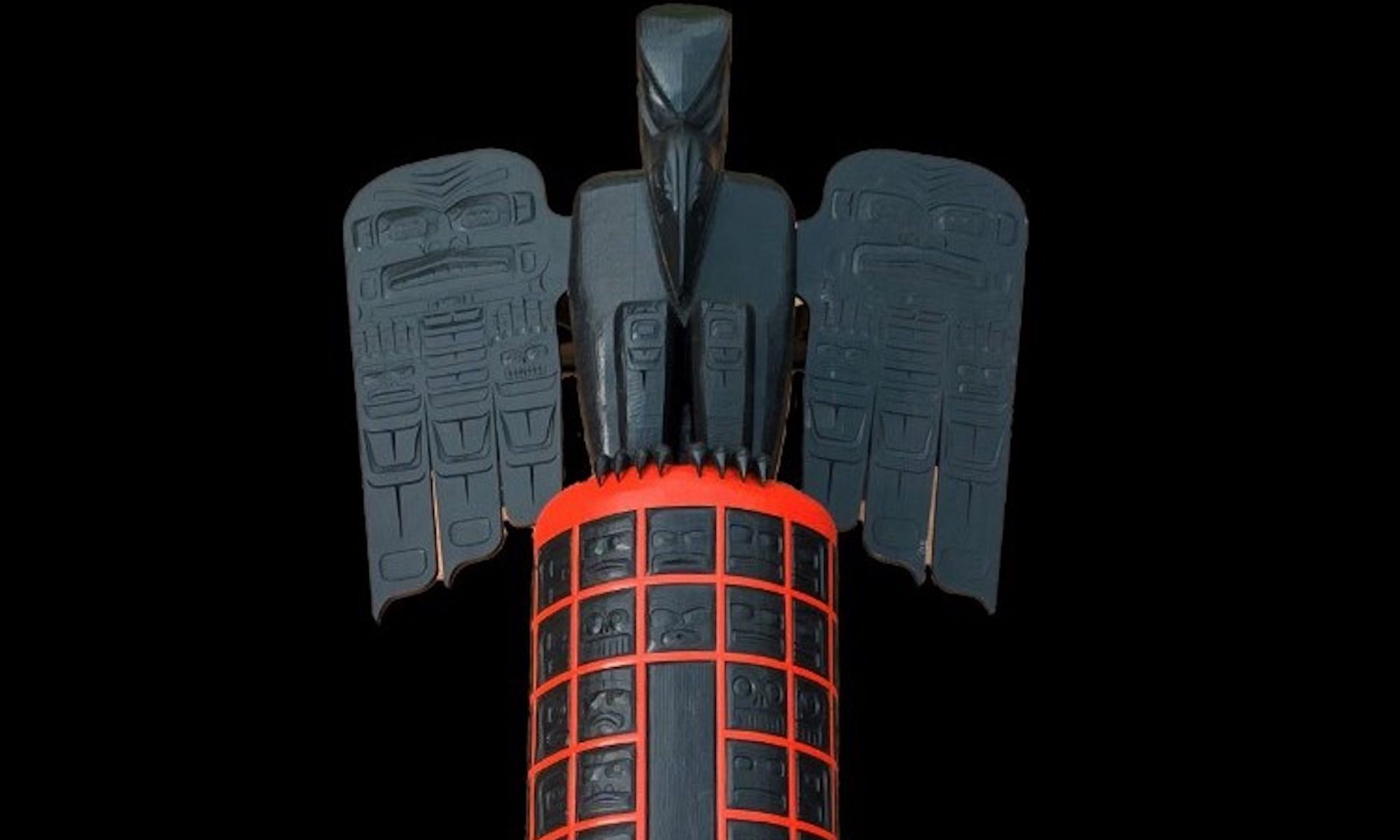

Stanley C. Hunt's Indian Residential School Memorial Monument (2023) photographed by a Royal Canadian Mounted Police drone Image © and courtesy of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police

Ahead of Canada’s National Day for Truth and Reconciliation (30 September), the Canadian Museum of History has acquired a monument and memorial to one of the country’s most shameful legacies: the residential school system that for over a century subjected more than 150,000 First Nations children to a process of forced cultural assimilation, often enabling many other forms of abuse in the process and leading to the deaths of still-unknown numbers of student. In 2021, the residential schools’ brutal legacy burst into the global spotlight with the discoveries of mass graves containing the remains of hundreds of First Nations children at the sites of former residential schools in Kamloops, Cranbrook and Penelakut Island, British Columbia, among other sites.

In response to the discovery in Kamloops, where the remains of 215 children were ultimately identified, the Kwakwaka’wakw artist Stanley C. Hunt created a massive sculpture featuring 130 carved, unsmiling faces—each representing an individual child—as a memorial. The resulting, 18ft-tall artwork, Indian Residential School Memorial Monument (2023), features a large raven—a figure that serves as a protector and creator—standing atop a cylindric wooden base painted orange, into which the 130 black-painted face carvings are set.

“The monument tells the truth about a time in our history that was dark,” Hunt said in a statement. “The monument identifies all the participants. The monument is black washed to mark that dark history. Orange to mark every child does matter. I did not write the history of Canada. I am marking a time in our history and to give our children a voice. The raven is cradling the seed of life in his beak. This raven has been created to help call our children’s spirit’s home. This raven will help us find and to identify the children. Through research and through DNA, my hope is to name all the children that are found. How would we ever know what these children could have become, if they were able to live a long and prosperous life?”

Since he completed it in June of this year, Hunt’s monument has been on a tour of western Canada. It is currently on display (until 10 October) at the RCMP Heritage Centre in Regina, Saskatchewan, a museum devoted to Canada’s federal law enforcement agency, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police. It will be a focal point of the RCMP Heritage Centre’s National Day for Truth and Reconciliation programming. The monument is expected to arrive at the Canadian Museum of History—located just across the Ottawa River from the capital in Gatineau, Québec—later this autumn and go on view there in next year.

Jade, Stanley C. Hunt's granddaughter, with the Indian Residential School Memorial Monument (2023) Photo © and courtesy Nicole Hunt

“This powerful memorial is a tangible reminder of events from our shared past,” Caroline Dromaguet, the Canadian Museum of History’s president and chief executive, said in a statement. “Its acquisition and eventual display in 2024 gives us new opportunities to spark national conversations related to reconciliation and the residential school system. We hope that visitors will not only be moved by the monument’s rich symbolism, but also be inspired to engage in thoughtful discussion and reflection around a difficult chapter in this country’s evolving story.”

Hunt is one of several First Nations artists who have made powerful works in response to the residential schools scandals in recent years. In 2017, the University of British Columbia erected Reconciliation Pole (2017), a 55ft-tall carved cedar monument by 7idansuu (Edenshaw), James Hart, a Haida hereditary chief and master carver. In addition to a rendering of the residential school Hart’s father attended, with a row of students holding hands above it, Reconciliation Pole features thousands of copper nails representing the thousands of Indigenous children who died in the residential school system; the nails were hammered into the wood by survivors of the residential schools, families affected by the schools, children and others.

Amid the outpouring of anger and grief that immediately followed the discovery of the unmarked graves at the former Kamloops school, the Haida artist Tamara Bell installed 215 pairs of shoes on the steps of the Vancouver Art Gallery. Her public gesture of protest and remembrance quickly became a collective shrine and gathering place for mourners.

In 2021, the Qayqayt First Nation artist Johnny Bandura created a sprawling mural imagining the lives that the 215 children whose remains were discovered at the former Kamloops residential school site might have lived. That work, like Hunt’s Indian Residential School Memorial Monument, has since gone on tour to serve as an educational tool and a gathering place for communities.