[ad_1]

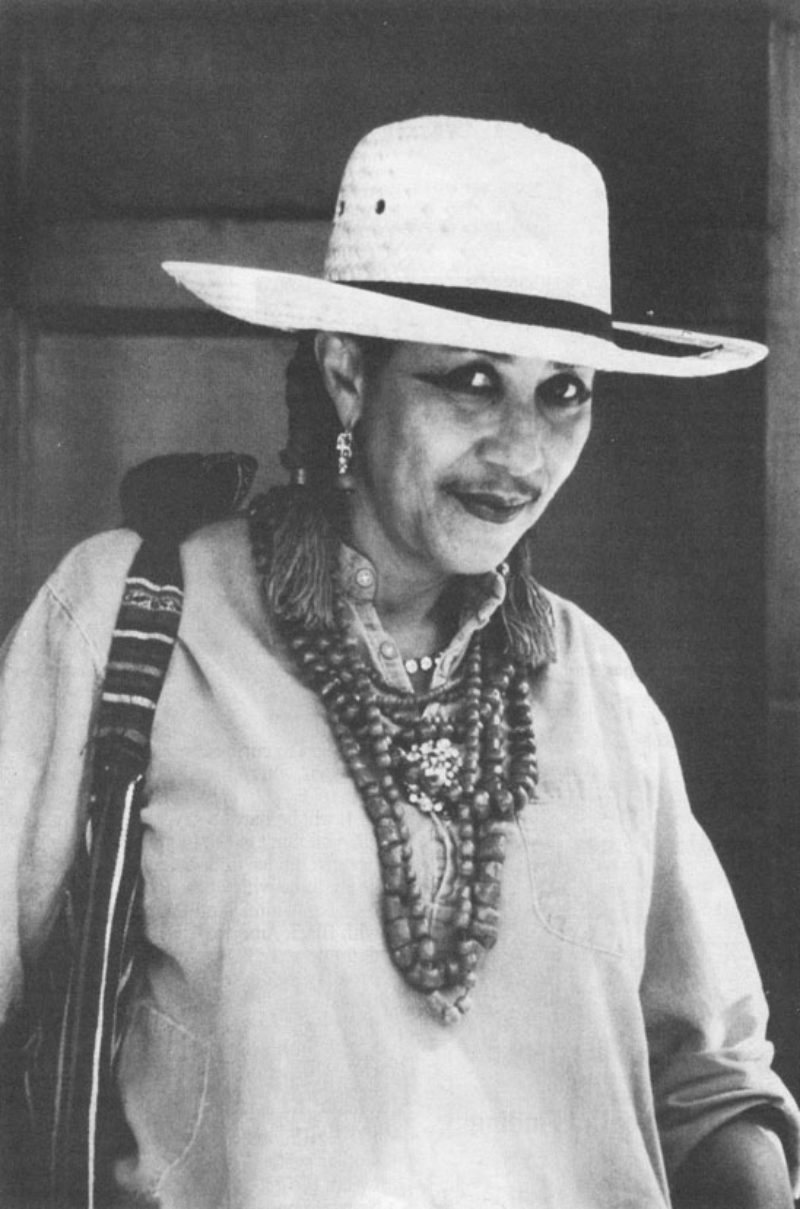

Camille Billops.

©1991 RUTH WILLIAMSON

Camille Billops, whose pioneering documentary films fearlessly and powerfully addressed difficult histories, has died, according to multiple postings online by friends and colleagues. She was 85.

A cause of death has not been confirmed, though a recent profile of Billops in Topic magazine said she suffered from dementia.

Billops is best known for documentary works like Finding Christa (1991), a 55-minute film that recounts why she gave up her four-year-old daughter and how they reconnected more than two decades later. (The film’s narrative is explored in-depth in the Topic article.) Like many of Billlops’s works, Finding Christa was made in collaboration with her husband, James Hatch, with whom she ran the production company Mom and Pop Productions.

Over the course of Finding Christa, which makes use of restagings, archival footage, and interviews, Billops tells of how, when she was 27, she left her daughter in a bathroom at the Los Angeles Children’s Home Society. “Why did you give me away?” Christa asks in voiceover at the film’s beginning. The reason, it turns out, was so that Billops could pursue an artistic career.

When it showed at the Sundance Film Festival in 1992, Finding Christa received the Grand Jury Prize for Documentary, making Billops the first black woman to win the award. In an essay that year in Artforum about black women directors, artist Lorraine O’Grady wrote that Finding Christa “expands the concept of the documentary into something for which I still can’t find a name.” The New York Times critic Vincent Canby called it “terrifically artful.”

For Billops, film offered a valuable way to archive narratives that might otherwise be invisible. Speaking of her tendency to create biographical work, Billops once told the writer bell hooks in an interview, “Put all your friends in it, everybody you loved, so one day they will find you and know that you were all here together.”

Some of her films dealt with broader histories of social inequity. The KKK Boutique: Ain’t Just Rednecks (1994) focused on racism in the U.S. by way of friends and colleagues of Billops and Hatch recounting instances of prejudice as a rejoinder to the notion that anti-blackness could be forgotten. “We Americans have tried to ignore it, deny it, suppress it, to contain it, tolerate it, legislate it, mock it, exploit it,” Billops and Hatch wrote in a statement accompanying the work.

Part of Billops’s larger artistic project involved ensuring that the voices of black women were heard. She began working as an artist during the 1960s, at a time when a group of black female artists such as Faith Ringgold, Howardena Pindell, and Emma Amos began calling for the formation of spaces in which they and other members of their community could show their art. Mainstream galleries generally did not show black artists’ work, so they took it upon themselves to change. “We were fighting so hard, but they wouldn’t let us in,” Billops once said. “So we said, ‘Well, fuck you and the horse you rode in on.’”

Their efforts were historicized in the touring exhibition “We Wanted a Revolution: Black Radical Women 1965–85,” which debuted at the Brooklyn Museum in New York in 2017 and included Billops’s work. For many, the show marked one of the first major opportunities to see Billops’s art in an institutional setting.

One of Billops’s most notable projects was not an artwork but a space. In the 1980s, she and Hatch rented a loft on East 11th Street in New York and began using it to show their friends’ art. The space also included Billops’s studio, Hatch’s office, and the couple’s extensive library of archival materials related to work by black artists. Their holdings—which wound up including more than 1,200 interviews with artists and more than 1,000 scripts by African-American playwrights, as well as related correspondences, photographs, books, and periodicals—are currently held at Emory University in Atlanta.

Billops also oversaw Artist and Influence: The Journal of Black American Cultural History, which focused mainly on work by African-Americans but also included interviews and articles about Asian and Latinx creators. One of the essential journals of its kind, it ran from 1981 to 1999.

Camille Billops was born in 1933 in Los Angeles. Her parents had come to California as part of the Great Migration, and she often described their view that she would grow up to be a mother—which she actively fought against. By the time she turned 10, she decided she’d never have children. After earning an undergraduate degree from California State College, she became a teacher to physically handicapped children in L.A. She then went back to school at the University of Southern California and received a degree in art.

In 1962, while in Egypt, where Hatch was teaching through a Fulbright fellowship, Billops had her first solo exhibition at Gallerie Akhenaton in Cairo. She showed ceramic works and sculptures, and she would go on to work in a variety of mediums, including photographs, collages, prints, and more. Many of her non-filmic pieces take the form of abstractions with figures that appear to morph into one another; they allude, in their titles, to histories of racism and harmful stereotypes.

In many cases, Billops talked about her art as a way of exposing matters from her personal life that, for many, would not typically be discussed. In interviews, she described audience members telling her that films such as Finding Christa were brave, and that she was surprised by their reaction. “Often, we don’t say things we should,” she said. “I tried to say those things.”

[ad_2]

Source link