[ad_1]

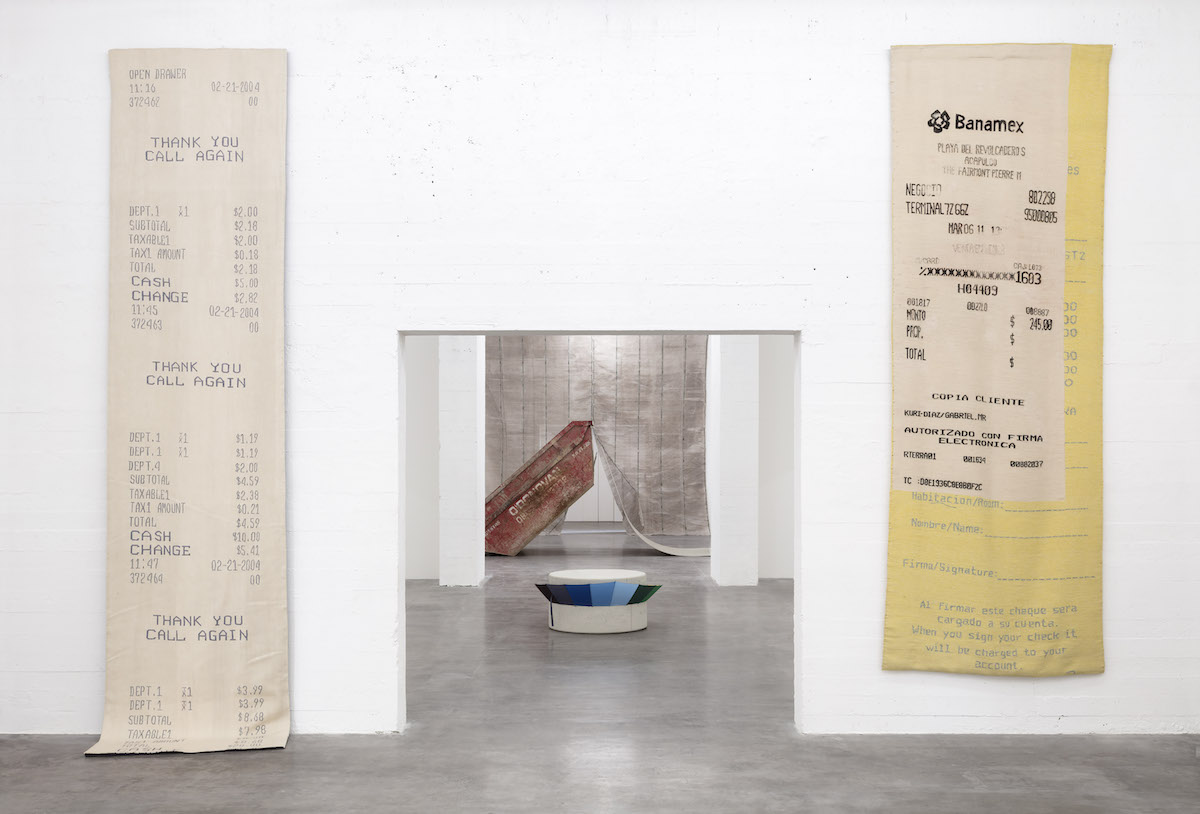

Installation view of “Gabriel Kuri: sorted, resorted,” 2019–20, at WIELS Contemporary Art Centre, Brussels.

COURTESY WIELS CONTEMPORARY ART CENTRE

‘It’s the little gray cells on which one must rely,” Agatha Christie’s wry Belgian detective Hercule Poirot once remarked, tapping his head. Such a cerebral approach applied to the strongest of the works on view at Brussels Gallery Weekend, a yearly event that took place earlier this month—and continues with some of the city’s galleries, institutions, and artist-run spaces exhibiting their brightest shows.

In a city that boasts an inordinate number of exceptional spaces for contemporary art, the best known is arguably the museum WIELS. Here, the Mexican-born, Brussels-based artist Gabriel Kuri has prosaic objects thoughtfully reconfigured and rearranged, all with an attention to consumerism and its discards. Organized into four sections according to their material—metal, plastic, paper, and disparate stuff such as concrete and insulation used in construction—they cumulatively reflect on the disposability of products and the trash we endlessly accrue. The Brutalist building’s high walls are littered with plastic bags attached to ceiling fans to create mobiles, like those that might hang above an infant’s crib. (Interesting fact! The first fully synthetic plastic was invented in 1907 by a Belgian-born chemist.)

Per the show’s press release, Kuri “knows how many beans make five,” an idiom I’d never heard before but that I’m told implies someone who is sensible and smart. While I agree in regard to “smart,” I’m not so sure “sensible” describes Kuri’s practice. His works are politically biting but also calculatedly off-kilter, often zanily so. Consider Concrete Pie (2009), an umbrella sandwiched impotently in concrete, or Untitled (Charted Missing Data), a work from 2016 composed of a hospital-like metal table on which an inflated condom stuck in stone rests.

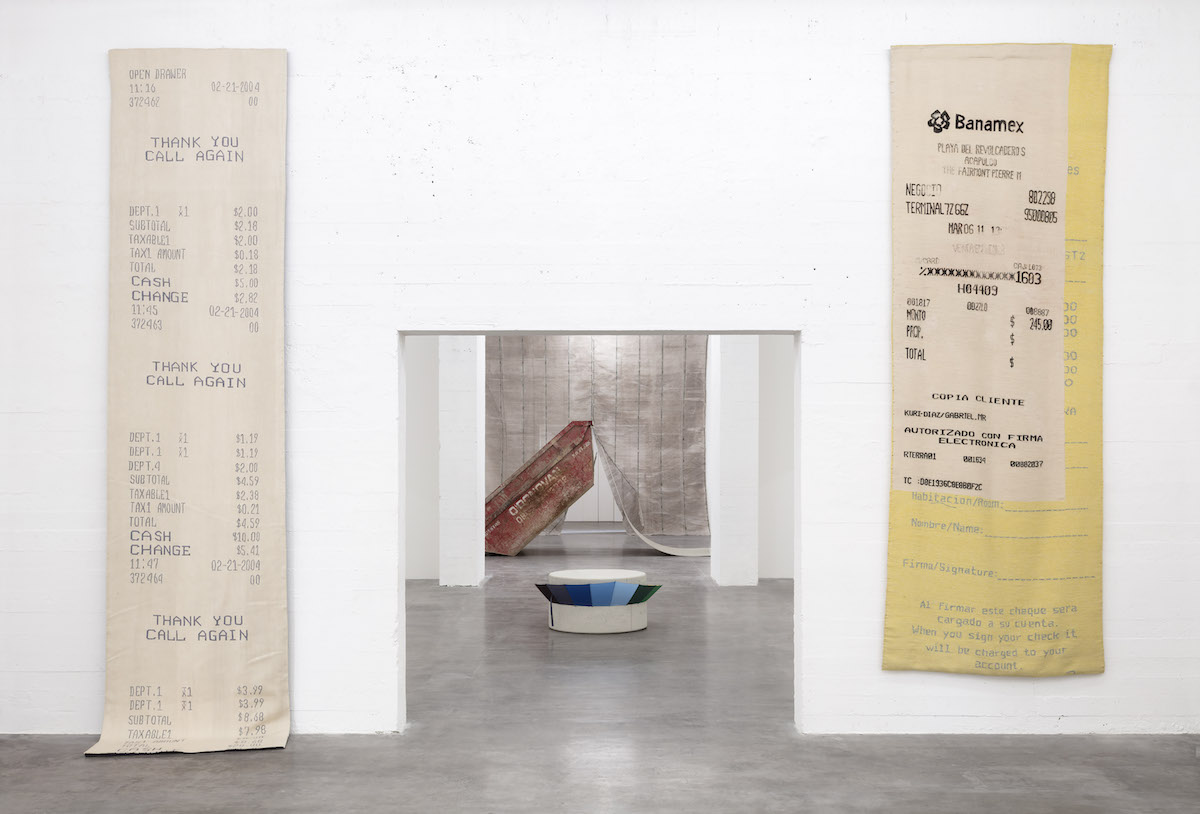

Installation view of “Zhang Enli,” 2019, at Xavier Hufkens, Brussels.

COURTESY THE ARTIST AND XAVIER HUFKENS, BRUSSELS

Meanwhile in the city’s Ixelles gallery district, the decidedly sleeker Xavier Hufkens Gallery, situated in a former townhouse, provides an elegant backdrop for the work of Zhang Enli, an artist from China. Enli is best known for painted abstractions with dusky palettes and gestural brushwork that appear curiously apocryphal, recalling Cy Twombly or even Claude Monet. Surprisingly, the artist has chosen to fill the gallery’s tallest and most dramatic room with a massive installation of stacked cardboard boxes. Hastily painted and taped together, they read as a retort to viewers who would pass Enlis’s work off as tasteful wall dressings for multi-million-dollar Tribeca pads. The attempt is a little too obvious (one can imagine Poirot rolling his eyes), but the structure itself is striking. While not as conceptually rigorous, it’s as visually impactful as the immersive installations of Thomas Hirschhorn, reminding you that transporting works can be constructed with cardboard and tape.

Farther uptown, Oscar Tuazon’s exhibition at Dépendance both seduces and confronts. The Los Angeles-based artist’s installation is anchored by two intimidating columns: one a steel drum with a halogen lamp that projects from a circular incision, the other a concrete tube with a circular aperture that suggests a fire pit. They’re placed in adjacent galleries like standing infantrymen. I was actually disappointed that no real fire was burning, but that’s modern life for you, I suppose—legal liability curtailing all gestures, art included. Nevertheless, it was easy to imagine scrappier times, perhaps those of the Minimalist and Land art movements that Tuazon riffs on, in which no one would blink an eye at a fire in a gallery. In any case, Tuazon, as always, is working to stage the tension between the two movements. His sculptures bring the outside in while insisting earthly phenomena can be constrained and contained, made orderly and symmetrical.

Amélie Bouvier, I Have Always Looked Up at the Sky, 2019.

COURTESY THE ARTIST AND HARLAN LEVEY PROJECTS/GILLES RIBERO

The greatest revelation of Brussels Gallery Weekend (and the weeks since, as the shows typically run longer) is far less stentorian: an exhibition by the artist Amélie Bouvier at Greylight Projects, a small subterranean gallery a few blocks from my hotel in a northern corner of the city. Here, the artist has mounted a show of monochrome inked drawings and video inspired by her extensive research of astrological imagery recorded between the 19th century and the present. The drawings are delicate and intricate; in meticulous line-work they respond to chartings made by scientists. In an adjacent gallery, a video shows documentation of the Harvard Archives, where photographic plates of the sky taken between 1877 and 1919 are currently housed. The workers who recorded them were entirely female and, as employees of Harvard educator and astronomer Edward Charles Pickering, were known as Pickering’s Harem. Now the plates have outlived their use and are seen being wiped clean by additional female hands, their notations erased from memory.

Brussels takes art quite seriously, as evidenced by the 40 galleries participating in a much-celebrated citywide event. The venues that participate show a willingness to take risks on work that is less safe and saleable than the usual September fare—and certainly more engaging of the little gray cells.

[ad_2]

Source link