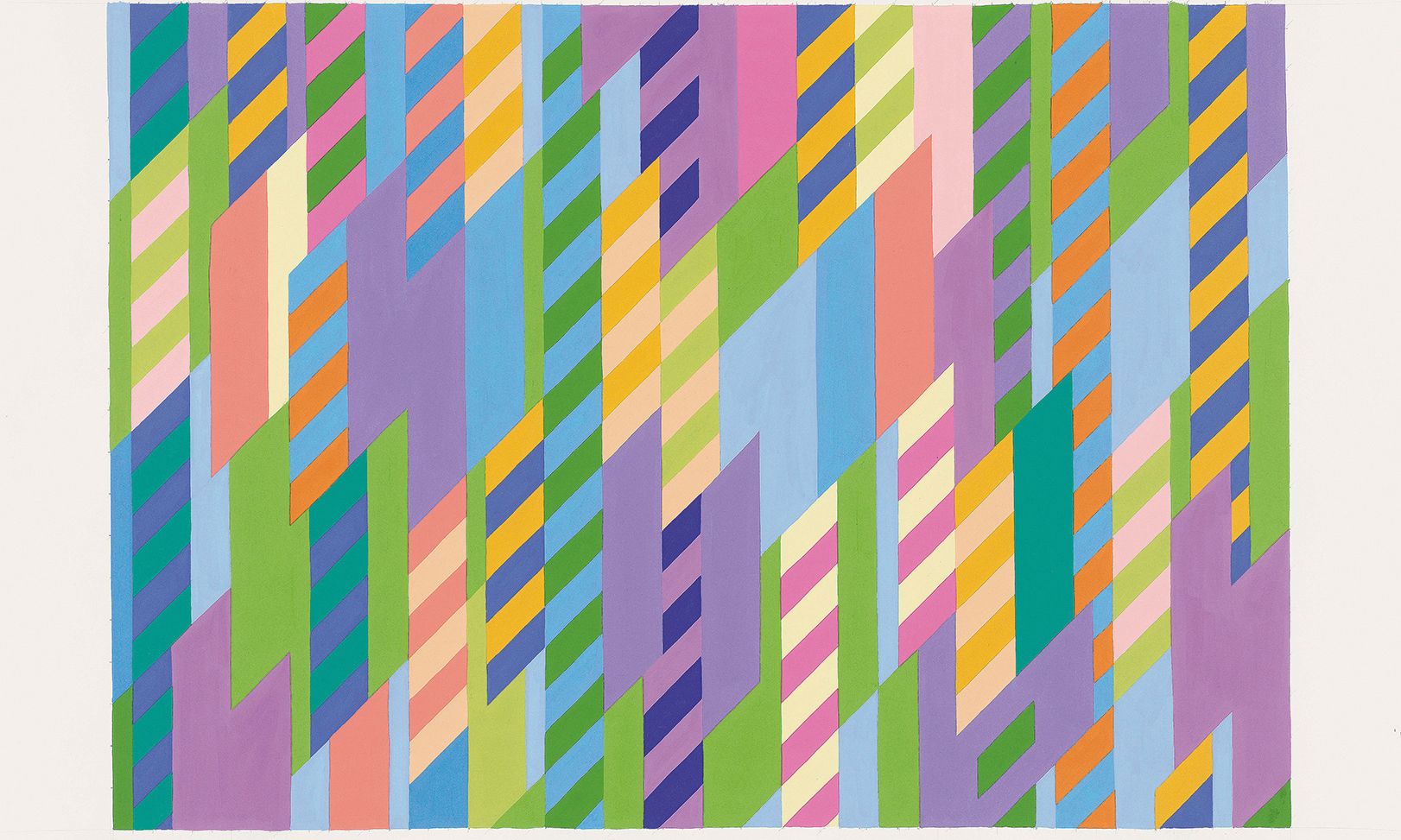

Bridget Riley’s pencil-and-gouache July 1 Bassacs (1994) demonstrates the artist’s shift away from the diagonals and curves typical of her earlier work towards an exploration of the rhomboid Pencil and gouache on paper. 27 × 35 7/8 in. (68.6 × 91.1 cm); collection of the artist; © Bridget Riley

Drawing, for the artist Bridget Riley, is an act of discovery, a way to learn by doing and to work through problems. The process is “an enquiry, a way of finding out—the first thing that I discover is that I do not know”, she wrote in her essay “Work” (2009). “It is as though there is an eye at the end of my pencil, which tries, independently of my personal general-purpose eye, to penetrate a kind of obscuring veil or thickness.”

Often studies or drafts for the intensely optical abstract paintings for which she has become renowned, Riley’s drawings have rarely been exhibited en masse. But together, they provide invaluable insight into her changing approach to line and colour over more than six decades, as the travelling show, Bridget Riley Drawings: From the Artist’s Studio, reveals. The exhibition, now at the Hammer Museum, brings together more than 90 works on paper selected from Riley’s London studios, many of which have never been displayed. It arrives in Los Angeles after debuting at the Art Institute of Chicago, and marks the first and most extensive exhibition of Riley’s drawings at a US museum in more than 50 years, as well as the artist’s first major show at a West Coast institution. Its final stop will be at the Morgan Library and Museum in New York in June.

Study for Movement in Squares (1961) cemented Bridget Riley’s move into abstraction Gouache on card. 6 ½ × 6 ¾ in. (16.5 × 17.2 cm). Collection of the artist; © Bridget Riley

A retrospective of sorts, the exhibition at the Hammer is arranged chronologically, with early works shown in a central room nested within the main gallery. Among these are richly toned landscape drawings from Lincolnshire, where Riley spent part of her childhood, and Conté crayon studies from life-drawing classes at Goldsmiths College, where she studied from 1949 to 1952. Drawing taught her how to look and to understand the potential of tone, leading to the illusive gradations she continues to explore.

“A lot of artists don’t consider their drawings to be preparatory, or working drawings, but Bridget Riley very much does,” says Cynthia Burlingham, the Hammer’s deputy director of curatorial affairs, who co-organised the exhibition. “They’re all generally related to paintings. Some didn’t end up being paintings, but in most cases, they did.”

An important work on view is a 1961 pencil-and-gouache study, for the painting Riley would call Movement in Squares—a grid of black-and-white squares with widths she systematically reduced and expanded so they appear to create movement across the picture plane. “It marked her first major foray into abstraction,” Burlingham says. “It’s this tiny little drawing, with pin holes from where it was pinned up in the studio. It’s in good condition, but it was very much used.”

These traces of use are part of what makes Riley’s drawings especially alluring. One pencil-and-gouache drawing on graph paper illuminates her careful consideration of colour, whose perceptual effects she started investigating in the late 1960s. Called Egyptian Stripes with Revisions (1983), it features cut-out strips of colour that can be moved across the paper’s surface, enabling Riley to see how neighbouring colours affect one another. Like many other drawings, it has pieces of tape adhered to it, and carries notes on colour or her process.

“She wants you to see how she gets somewhere,” Burlingham says. “She’s very much about showing that progression. I found that a very revelatory practice.”

The exhibition includes just one painting, a scene of trees and buildings done in a pointillist style, in 1959, when Riley was copying works by Georges Seurat, one of her primary influences. Called Blue Landscape, it is accompanied by three studies: one dedicated to line, another to tone and the third to colour. This process changed when Riley moved into abstraction, but it illustrates how, as Jay A. Clark, the Art Institute of Chicago’s curator of prints and drawings, writes in the exhibition catalogue, Riley “was discovering and inventing all along”.

Bridget Riley Drawings is, in a sense, a companion to a major Riley retrospective in 2019 co-hosted by the National Galleries Scotland and the Hayward Gallery. That show included drawings alongside paintings, and its organisers reached out to the three US institutions proposing that they co-organise an exhibition focused exclusively on drawings. “A lot of audiences in the US haven’t seen this work, so that was an opportunity,” says Burlingham. “And it’s an opportunity because Riley generally keeps her drawings for reference, to use to continue her work in different ways. They’re very important to her to have to hand.”