[ad_1]

The Ghanian sculptor worked with cheap, commonly found objects for decades until he arrived at just the right one

By El Anatsui, The Guardian

It wasn’t normal for someone like me to become an artist. Growing up in rural Ghana, there was nothing like a museum or art gallery, and nobody pursued art as a profession, so I had no role models. When people heard I was going to study art, they wondered what precisely I would do when I finished. But I knew that I would go on to practise as an artist. I knew I was going to enjoy it and be on top of it.

It was in art school in Kumasi that I developed interest in sculpture. It was more free and versatile to me than painting or textiles or ceramics, and almost all the other forms are present within it. At that time there were terribly few books about African art or sculpture, but in the few that I could access, I saw that the artists were more interested in interpreting the human figure than copying it. And they showed very great understanding of the media they worked with, be it clay or wood – they knew how to handle it so that it had integrity.

Later on, at the National Cultural Centre in Kumasi, I was introduced to more African work, and what attracted me were the pictograms I saw printed on fabrics. These pictograms were trying to capture abstract concepts, such as God’s omnipotence. In the Renaissance, abstract concepts such as virtue were given a human form, but these artists were grappling with abstract concepts without reference to the human body.

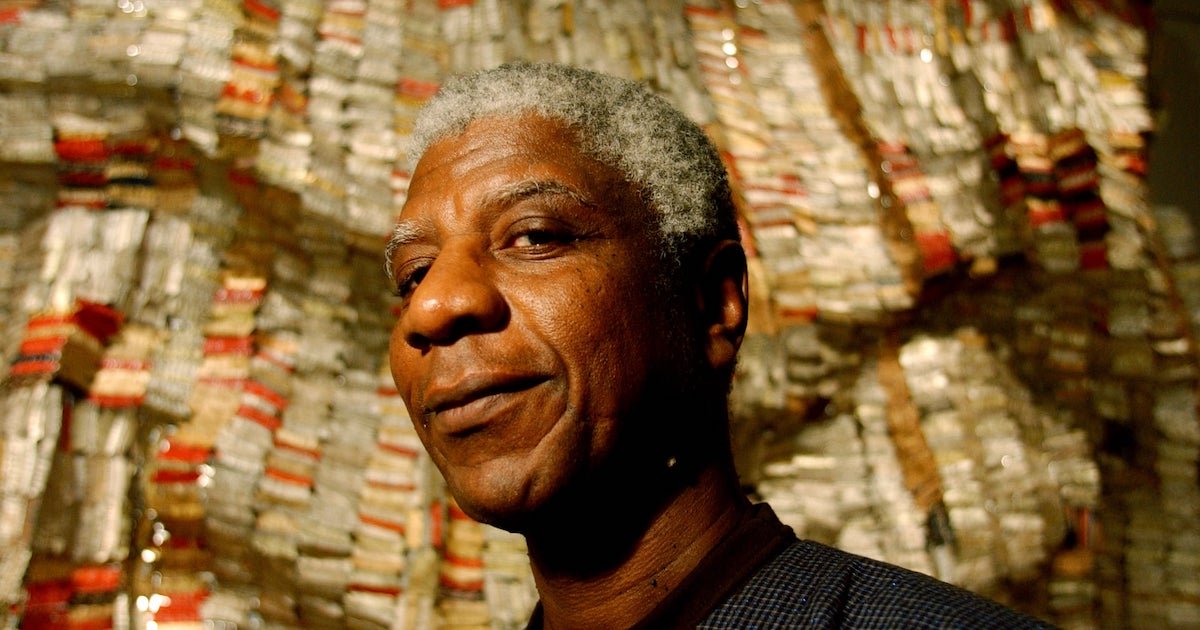

Featured Image, Sarah Lee/The Guardian

Full article @ The Guardian

[ad_2]

Source link