[ad_1]

Francis Picabia’s Les baigneuses, femmes nues au bord de mer (1941), on view at the booth of Hauser & Wirth.

ARTNEWS

“Picabia Alert” takes note of shows and publications that include the wily French artist Francis Picabia (1879–1953). It ran in these pages up until the 2016 retrospective of the artist that appeared at the Kunsthaus Zurich and the Museum of Modern Art in New York and then went on hiatus. Now it is back.

The 49th edition of Art Basel in Switzerland, which opened Tuesday and runs through Sunday, is overflowing with works by the great Francis Picabia.

Galerie 1900–2000’s booth, combining a Cindy Sherman wallpaper piece with Picabia drawings.

If you have been reading coverage of the fair, you may have heard about the most jaw-dropping display of the artist’s work. That’s the one at the booth of Paris’s Galerie 1900–2000, which has arrayed eight drawings of women’s heads—seven from the early 1940s, one from 1933-34—atop a Cindy Sherman wallpaper piece (with Sherman’s permission). It’s an exhilarating master class in portraiture and ways that identity can be refracted by artists working in very different fashions.

Works by Picabia in the booth of Galerie 1900–2000, with Seville, 1939–42, at right.

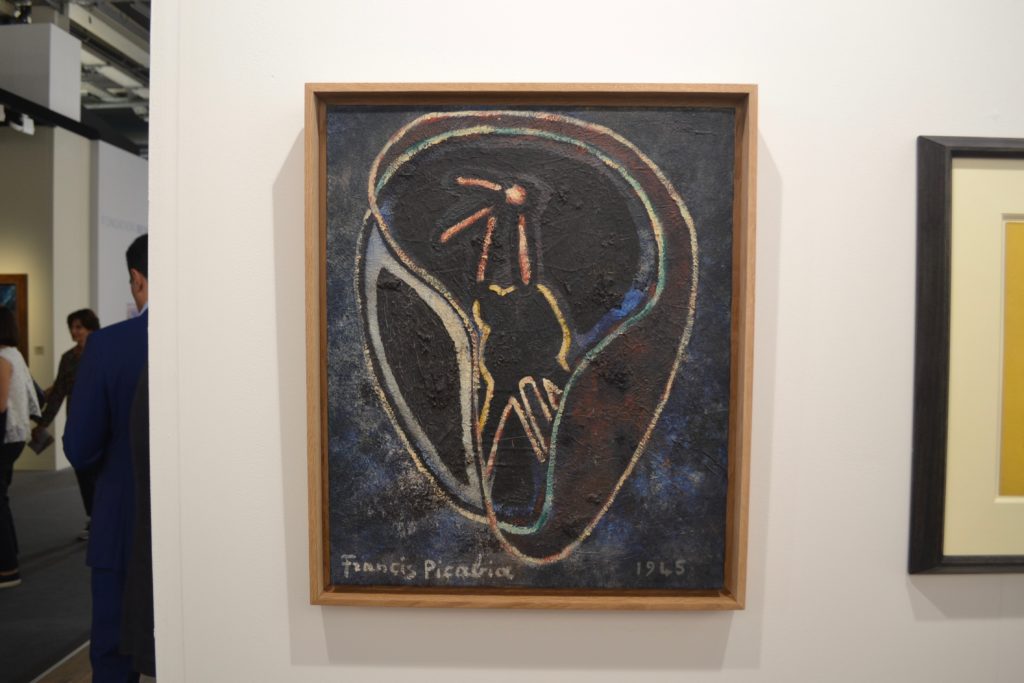

But that is not all that Galerie 1900–2000 is showing. Here, too, is Picabia’s Seville (1939–42), a painting of a woman wearing a mantilla (a subject the artist returned to over many decades), which is accompanied by another tranche of drawings, including some full female nudes and one of two overlapping heads that float inside an undulating blob. And there’s a 1945 painting of what might be a kind of abstract bird floating through deep space. I could spend all day in that booth.

Le negativeteur du hasard, 1946, at Haas.

Eventually, though, one has to leave, and thankfully there are other booths that can provide a Picabia fix. Over at Berlin’s Galerie Michael Haas, which is always a dependable source of works by the artist at fairs, there’s a large and late abstraction from 1946, of a kind of green-yellow head shape being attacked with cones. It’s titled Le negativeteur du hasard, and it’s dated 1946, seven years before the artist died, at the age of 74.

Francis Picabia’s Portrait de femme, ca. 1941–42, next to Peter Saul, at Michael Werner.

Michael Werner, another longtime Picabia specialist, had no fewer than three works by the artist hanging on Art Basel’s opening day. Portrait de femme (ca. 1941–42), a quite glamorous portrait from a series that the artist often made based on publicity images, was on show alongside a 1962 painting by Peter Saul. And at the other end of the booth were two more works by Picabia: a deeply weird, almost-cartoonish image of a woman seen in profile from 1935 and an almost Charles Burchfield-y landscape from around 1938 titled Les Oliviers.

Francis Picabia’s Les Oliviers, ca. 1938, and Untitled, 1935.

Finally, the multi-gallery empire Hauser & Wirth, which a couple years ago mounted a toothsome show pairing Picabia with Alexander Calder in Zurich, had a brightly lit—and, of course, very strange—painting from 1941 of three nude women being gawked at by a figure with slick, closely cropped hair emerging from the bottom edge of the canvas and seen from behind.

Marcel Dzama’s Let the women rule after the clown is through, 2018, at Sies + Höke.

If one were to list the many artworks at Art Basel that have been in some way informed by Picabia, we could be here all day. But there is one that steals from the maestro with delightful results. Pretty much a direct copy of the 1941–42 painting The Adoration of the Calf (which itself was based on a 1937 photograph by Erwin Blumenfeld) with a few cartoon figures added, it’s a 2018 work by Marcel Dzama being shown by Sies + Höke of Düsseldorf. It has the kind of piquant title that I can imagine Picabia enjoying: Let the women rule after the clown is through.

[ad_2]

Source link