Ask Philly basketball fans to name one of the city’s best professional teams, and they will probably say the 1967 or 1983 Sixers. A few experts might mention the 1956 Philadelphia Warriors. But even the most devoted fans probably have not heard of one of the greatest and most important Philadelphia basketball teams of all: the 1928-1929 Quaker City Elks.

The Quaker City Elks, also known as the Giants, date back to a time in basketball when Black players were excluded from playing in all-white professional leagues. While baseball’s Negro leagues of the early 20th century have been well-documented, the story of the first professional Black basketball teams is not nearly as known. A handful of historians have worked to revive interest in the early years of Black basketball, but even these efforts have mostly overlooked the amazing story of how the 1928-29 Elks overcame huge obstacles to become, as Jack Saunders, a sports editor and columnist at the Philadelphia Tribune wrote in 1941, “probably the greatest professional team Philadelphia has ever produced.”

***

I discovered the 1928-1929 Quake Elks while volunteering to help put together an exhibit on the history of Philadelphia basketball for the forthcoming Alan Horwitz “Sixth Man” Center. The exhibit is being overseen by Lucas Monroe, a star guard for the University of Pennsylvania’s basketball team. Monroe gave me the job of researching Philadelphia basketball teams from the first part of the 20th century.

As a fan of the sport, I was already a little familiar with the very early history of basketball. The sport was invented by James Naismith in 1891. Basketball came to Philadelphia around the turn of the twentieth century. When the game first started to be played, there were very few opportunities for Black Americans to play. By 1907, boys were playing basketball at the all-Black Wissahickon Boys Club. The game also spread to Philadelphia’s Black YMCAs, including the Christian Street YMCA, the first Black YMCA to have its own building.

As I read through old newspapers, I could see evidence of the racism the first Black basketball players faced. One 1909 newspaper I found included an incredibly offensive joke about Black players using a watermelon to play basketball. By the 1920s, Black teams were traveling the country in search of games, often playing white teams and enduring hostile white crowds. These Black teams usually couldn’t even find hotels or restaurants that would allow them in.

Because the Black teams did not have access to gyms, their home games were held in dance halls such as Philadelphia’s famous Palais Royal. The crowds danced before and after games. The waxed dance floors could make it nearly impossible for players to run and jump.

The best and best-known Black team of that era was called the New York Renaissance. Formed in 1923, the Rens became a basketball powerhouse that dominated the sport for decades, trouncing not only other Black teams but also the white teams of the era who had many more resources.

Philadelphia’s Black pro-team in the mid-1920s, the Panthers, wasn’t in the same class as the Rens. The Panthers “would not dare a game with the New Yorkers,” one sportswriter at the time recalled. But the Panthers did have a core of talented young players who had worked on their skills as the Christian Street Y. What Philadelphia’s Black basketball community needed was a manager who could put together a team that wouldn’t be afraid to step onto the court with the Rens.

That basketball manager turned out to be a retired left-handed pitcher from the Negro Leagues named Danny McClellan. McClellan is believed to have pitched the first perfect game in the history of Black baseball in 1903. After retiring, Danny McClellan became a baseball manager, and one of the players on his team, Billy Yancey, also happened to be one of the best basketball players in the world. Legendary college basketball coach John Wooden once described Yancey, a product of Philadelphia’s Central High School as “the greatest outside shooter” he had ever seen.

With Billy Yancey’s help, Danny McClellan began to recruit basketball players from the Panthers and other Philadelphia-area teams. One key recruit was Jackie Bethards, a great ball-handler. A newspaper of the era described Bethards as “one of the slickest floorworkers in the game.” Bethards was sometimes referred to as the “clown prince of basketball” because of his on the court antics. Other standouts were guards Charlie Mitchell, James “Slats” Davis and “Handsome” Tom Chambers.

The most important recruit of all turned out to be Charles Theodore Cooper, another product of Central High School and the Christian Street YMCA. Cooper was 6’4, which was extremely tall at the time, and solidly built. He was known for his defense, rebounding, and clutch scoring. According to one 1931 article in the Philadelphia Tribune, Charles Theodore Cooper represented “the pinnacle of artistry attained in modern basketball play at the center post.”

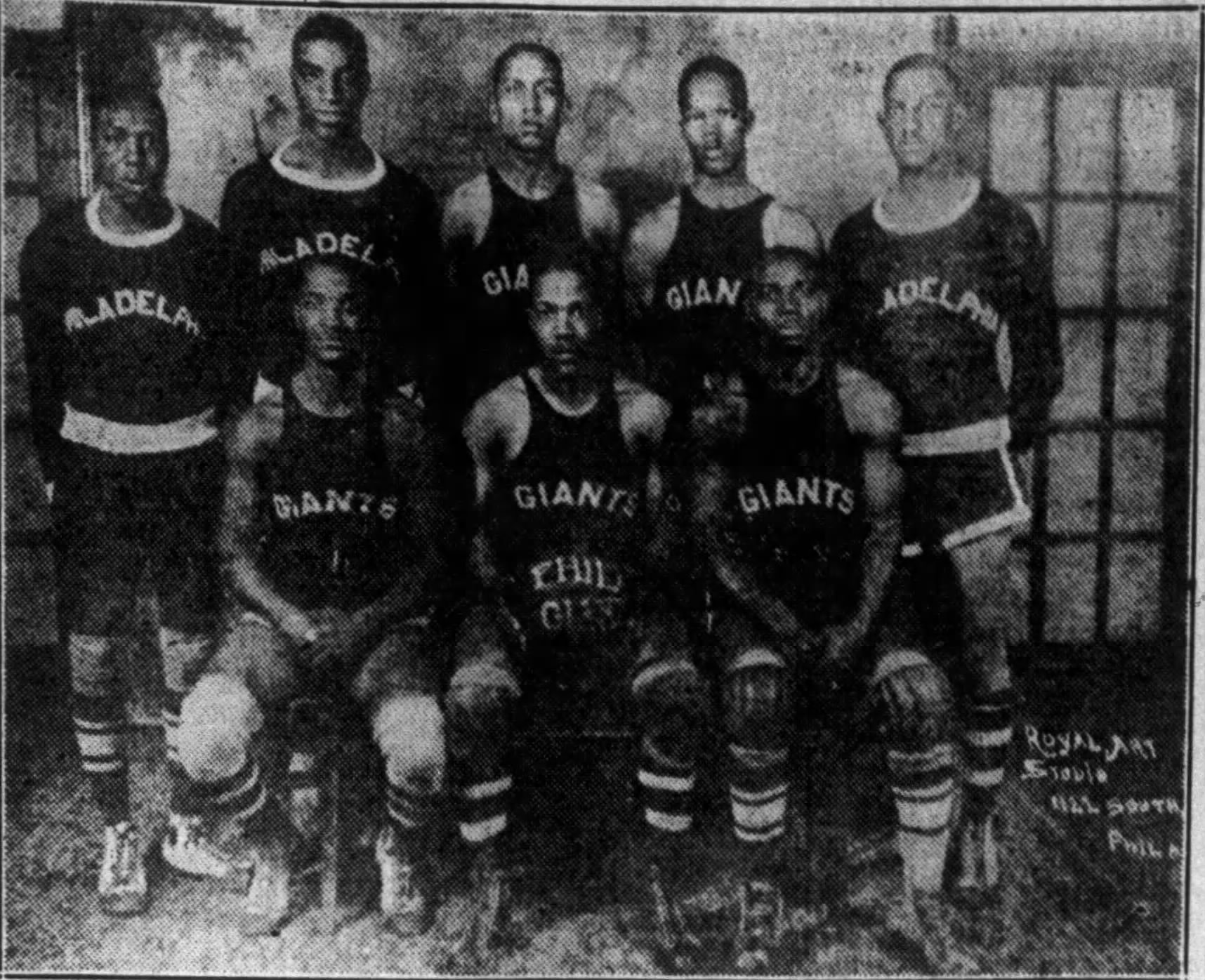

The new team, sponsored by a Black fraternal order in Philadelphia, was known as the “Quaker City Elks,” although they would later also play as the “Philadelphia Giants.” Even with the support of the fraternal order, money was scarce. “We thought we were pretty good,” Cooper recalled years later, and “sunk most of our meager earnings, plus that borrowed from some friends,” to form the team.

The Elks played their first game on December 29, 1927 against the Atlantic City Buccaneers and won 25-23. Seeing the team’s potential, McClellan wanted to arrange a game against the Rens. Bob Douglas, founder of the Rens, and sometimes called “the father of Black professional basketball,” wasn’t initially eager to play the Elks, but eventually agreed to do so for seventy percent of the ticket sales. The first meeting of the two teams took place in Philadelphia on January 9, 1928.

Nobody would have bet on the Elks. The Elks were smaller than the Rens. And they had only played their first game a few weeks earlier. The two thousand fans in attendance must have been surprised the Rens were only up two points at the half. That lead increased in the second half, and with no shot clock at the time, it was hard for a team to make a comeback. At one point in the game Ren’s star Fats Jenkins dribbled the ball for two straight minutes.

The Rens won by 10, but the Elks had shown they could compete with the best. McCellan took them on a tour of New England where they began to obliterate the competition and ended up winning 31 out of 40 games. Bob Douglas appeared to have been rattled by the Rens first meeting with the Quaker Elks and began to belittle Philadelphia’s new team when speaking to the media. It didn’t help that, as the Elks racked up wins, some were beginning to refer to them as “the world’s colored champions.” One sportswriter nicknamed the Elks “the flaming youths.”

In the first week of March 1928, the Elks and Rens faced off for a second time, this time in Boston. It was tense from beginning to end, with neither team managing more than a two-point lead at any point during the entire game.

The Rens became physically aggressive in the second half, but the Elks didn’t back down. The Pittsburgh Courier described it “one of the roughest games ever witnessed on a local court.” The Elks went up by two with less than four minutes to go. That’s when Jackie Bethards took over. A skilled dribbler, he managed to keep the ball away from the Rens for three consecutive minutes while being hounded by Fats Jenkins. In the end, as the Philadelphia Tribute put it, the “Rens were treated to the surprise of their lifetime.” The Elks, less than three months after coming together for their first game, eked out a one-point victory, 27-26.

“Then, as now, the Rens were the hottest outfit in pro basketball,” Cooper wrote in 1943. We “were a bunch of youngsters who had grown up around the Christian Street YMCA.” Cooper added that, at the time, he had no idea that he would be able to make a career out of playing basketball.

By the time the Elks returned to New England the following January, The Philadelphia Tribune was referring to the Elks as “Philadelphia’s pride”: “The Quaker City Elks are once again causing sleepless nights for basketball managers down east.”

The Elks won 9 of their first 13 games on their trip. Yancey, though not typically one to boast, publicly called for another match against the Rens. A month later, Yancey got his wish. The two teams met in Boston again. At halftime, the score was 11-11. The Elks got some help from the Rens, who missed some easy shots throughout the first half. As one newspaper described it, the “sphere time and again hit the rim of the basket,but refused to be pocketed.” “Handsome” Tom Chambers may have saved the game for the Elks by shutting down Rens’ star Pappy Ricks with suffocating defense. The Elks, having already shocked the Rens once, did it again. The final score was 25-22.

On March 13th, 1929, an article in the New York Amsterdam News, acknowledged that the Elks (now playing as “the Giants”) had “installed themselves as world champions” by beating the Rens. The Rens did get revenge on the Elks later that month in a home game at the Renaissance Casino, winning by a score of 35-24. Nevertheless, Rens manager Bob Douglas had seen enough of the Elks. He made offers to Yancey and Cooper that they couldn’t refuse. With the two new Philadelphia Stars on their team, the Rens would become virtually unbeatable. In 1933-1934, they won 88 consecutive games. Cooper would be widely hailed as the greatest center of his era.

As the early days of Black basketball have been rediscovered, the Rens have been considered the dominant team of the era. That is fair—there is no disputing what the Rens accomplished. But the Quaker City Elks/Giants have been forgotten. And Cooper and Yancey weren’t the only players the Rens hired away. Bethards would also later join the Rens, and also Zach Clayton, a rising Philly star who would also eventually be enshrined in the Basketball Hall of Fame.

If the Rens had not had the money to sign away Philadelphia’s star players, it may have been the Elks/Giants that people remember as the greatest team of that period. But this much is clear: in the last years of the 1920s, a group of young Philly guys from the Christian Street Y managed to take down the champions not once, but twice. For that accomplishment, the team deserves a place in basketball history.

Charles Theodore Cooper ended up playing for the Rens for 11 years. While he was on the team, the Rens won 1303 of 1506 games. The entire team was later elected into the Basketball Hall of Fame. (In 1977, Cooper was also inducted into the Basketball Hall of Fame as an individual.) He won the pre-NBA World’s Championship with two different teams.

The Hall of Fame webpage for Cooper doesn’t mention his time with the Elks/Giants. But at the end of his playing days, when he was asked to name “the greatest thrill” of his career, his answer wasn’t playing for the Rens. It was playing against them and beating them as a member of Philadelphia’s own Quaker City Elks.

Do you find this information helpful? A small donation would help us keep this available to all. Forego a bottle of soda and donate its cost to us for the information you just learned, and feel good about helping to make it available to everyone.

BlackPast.org is a 501(c)(3) non-profit and our EIN is 26-1625373. Your donation is fully tax-deductible.

Charles Cooper, “My Greatest Thrill,” Pittsburgh Courier, April 24, 1943; Randy Dixon, “Tatie Cooper, Philadelphia Boy, Hailed As The Best Center Of Modern Basketball,” Philadelphia Tribune, December 10, 1931; Joseph Rainey, “Elks Squeeze Out Victory Over The Buccaneers, 25-23,” Philadelphia Tribune, December 29, 1927.