Big Apple Blues: Greg Tate on the Art of Lockdown and Days of Rage

The four of us began quarantine in mid-March with, appropriately enough, a “Last Supper” against the backdrop of a balmy, preternaturally quiet, and already desolate central Harlem night. The worthy constituents were myself and three of my besties: BG and HK, two academics who are also curators, and our host, the doyenne TC, a movie producer who has worked many years with various legendary Black indie filmmakers.

TC and BG are both serious foodies and spectacular cooks; HK and I are both serious eaters, especially of their fine fixings. TC is also a much-loved thrower of grand dinner parties in her immaculate art-lined Harlem apartment. It’s where many of the neighborhood’s veteran boho-activist cognoscenti and ninjarati have spent several recent New Years’ Eves reveling until the breakadawn.

On the menu for our “Last Supper” before lockdown was a three-mushroom, three-cheese pasta with broccoli rabe, steamed salmon, and a light salad. We spent a fair amount of time talking about TC’s upcoming breast surgery. She’d decided on a full mastectomy (“Take the titty,” she reported telling her doctors). There was some question as to whether her surgery would be regarded as elective rather than essential under quarantine rules, but she was able to have the procedure as scheduled and came through with her ready wit, aplomb, and savoir faire intact.

When we left TC’s place and took a cab uptown, it would be another three months before we all gathered together again—that time for a picnic on the Hudson River around 135th Street, while a very muted Black Lives Matter protest for George Floyd shut down the West Side highway nearby. The sun was in glorious spring bloom, the air was warm and tender, the curve had officially flattened, and once again New Yorkers were out on the grass at water’s edge, picnicking, parlaying, and kicking classic funk and soul out of their boomboxes and portable speakers.

Like every other musician, lecturer, curator, and nomadic academic intellectual we knew, we all began our first week of sheltering in place by taking stock of all the things now removed from the gig calendar. I realized that, at this point in my hectic sexagenarian life, if I left my hood, it was usually either to go to the airport or a rehearsal of my band in Bushwick or on an Amtrak train to Boston, where, for the past year, I’d been working on a major exhibition with the Museum of Fine Arts.

Jean-Michel Basquiat, Six Crimee, 1982.

©Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat. Licensed by Artestar, New York.

Scheduled for an easy April opening but postponed for a later date (in October, as of press time), “Writing the Future: Basquiat and the Hip-Hop Generation” is a show I co-curated with Liz Munsell (MFA’s curator of contemporary art) that sets Basquiat works among others by those in his Black and Latino artistic community of the ’80s: Fab 5 Freddy, Rammellzee, Futura 2000, Lady Pink, Lee Quiñones, LA2, Toxic, A-One, and Kool Koor. “Writing the Future” is a multidisciplinary show that includes paintings, music, fashion, video, and installation works produced by that glamorous gang of streetwise creatives in the period. No one got to see it as it was supposed to open in the flesh, but we did manage to get our gorgeous catalogue published under the quarantine wire—and we also did a soft Instagram launch on the original opening weekend. Plans for a traveling version to go to the Pérez Art Museum in Miami were canceled, but our donors agreed to let the MFA hold on to the artwork until next spring. We talked about the possibility of a socially distanced opening to the public in October or November, but at the time I’m writing we can only wait and see.

Also canceled was a public reading of Hello Darknuss: The Radical Black Futurist Imagination vs Slavery, Inc., my forthcoming book on the union and entanglement of Black politics and aesthetics, that instead became my introduction to presenting on Zoom. A meeting of advisers for an Afrofuturism exhibition scheduled for the fall in Barcelona turned into a Zoom convening in July. And the plan was nixed for my 17-piece conducted-improv big band Burnt Sugar the Arkestra Chamber to play our favorite jazz festival in Sardinia near the end of August. So was an offer for the band to appear at a community music fest just three blocks from my Sugar Hill crib. (Though we did manage to get in one last big show at the end of February: a performance of a live orchestral score to Shaft at the Apollo Theater.)

Within a couple weeks after we’d all absorbed news about the virus’s devastating death toll across New York’s five boroughs, I got asked to participate in two anxious but optimistic Zoom conferences about “Culture After Covid” convened by local arts organizations. I recall speaking measuredly at the first one (organized by the Brooklyn performance space BRIC) about our need and responsibility to first address the massive trauma and mourning that will be running concurrent with whatever else is happening when museums and galleries and performance venues open up again. I also went off on a magical-thinking tangent about the rejuvenating powers of conjuration possessed by the Black American community, our historic and relentless pursuit of beauty which perseveres despite the horrors visited upon Blackfolk by state-sponsored systemic racism, anti-Black policing, the prison-industrial complex, blah blah, etc. etc.

Futura 2000, Boombox, 1983.

Courtesy Wave 5 Communications LLC.

Like many folks, I experienced those first few weeks in purgatory as a time of near-Zero G freefall, a time where days and nights blurred into one long Wednesday when you were to prepare your first major meal at 1 a.m., stay up binge-watching Netflix until dawn, and then sleep until 4 in the afternoon. I get strong and direct Eastern light at sunrise and for some prescient reason had decided, in February, to invest in some thick cotton-polyester night shades for the bedroom—the smartest home decorating improvement I’d made in years. My favorite Netflix discovery of those early weeks was a Japanese series called Midnight Diner. It features a tall, fit, taciturn, welcoming, and laconically wise chef-owner known as “Master” whose spot in Tokyo is only open from midnight to 7 a.m. Master’s specialty is a pork-laden miso soup shown in the weekly intro as a mouthwatering and bubbling broth, but he will also make whatever customers request if he has the ingredients.

Watching Midnight Diner dovetailed with my casual decision to cook all my own meals during lockdown. Like many a bachelor, I’ve learned to boil water. Like many a non-beef-chicken-or-pork eater, I can toss off a mean fruity salad (mesclun-spinach blend with watermelon, avocado, blueberries, strawberries, pear, goat cheese, pecans, and shiitake-sesame vinaigrette by Anne’s). Like many a pescatarian, I can conjure up a savory fish stew, mostly fresh cod ornamented with red potatoes and shiitake mushrooms. My family’s Memphis heritage shows up via my balsamic-vinaigrette-splattered collard greens cooked with red and green peppers and, a personal invention, a chunky cornbread casserole with zucchini slices, ricotta, and Sicilian herb tomato sauce cooked inside.

I’d made a point of getting out every day for light and air in my Dominican Heights hood, masked up (or scarfed up, really). Living around Caribbean folk, even on lockdown, you never stop feeling like you’re in a teeming, family-oriented village where essential life goes on despite the nonstop screaming symphony of ambulance sirens that owned the ambience night and day those first two months. I eventually learned that Manhattan was the least hard-hit of the five boroughs, but that my ZIP code and three adjacent in Washington Heights and Inwood were in the Top 10 of the borough’s fatalities.

My immediate family is spread across five states, and we started Zoom meetings every Sunday a couple weeks in, gathering the tribe spread out over New York, Rhode Island, Virginia, Florida, Georgia, and Washington, D.C. We decided to give each week’s calls themes: current reading, best meals ever, most remarkable travel adventures. The dopest was my 12-year-old niece’s introduction for her elders to the madcap world of TikTok. One filmmaker has called it the future of cinema, and I can dig it, given that moviemaking as we knew it will likely be one of the last major cultural industries to return to the New Abnormal.

For my part I also finally discovered creative curatorial uses for my Instagram page. Before purgatory, I’d only occasionally posted random family photos or a noteworthy street scene. But I suddenly decided I wanted to use the triangulation of phone, laptop, and iPad to concoct some provocatively surreal mash-ups of music, narration, and performance from unrelated sources. A couple of these quickly drew enough attention to let me know I was being followed, and I also dropped several live performances on bass and guitar that drew small appreciative crowds. Strolling cinema verité of my Dominican neighbors reopening earlier than Governor Cuomo likely intended also became an IG staple—capturing my Dominican peoples’ spontaneous and multigenerational street parties replete with smoking hookahs and old men slamming dominoes.

By mid-May, you could feel we had made it through something and come out on the other side as survivors of quarantine phase one. It was officially spring and the concert of sirens had de-escalated from nonstop to every now and then. As we all started to relax a bit, we took note of other sounds in the night—like the ritual 7 p.m. banging of whatever ya got in praise of the frontline medical workers working their shifts.

Members of my band—which includes several rock-star geezers well over 60 and others between 40 and 50—had come through the slaughter more or less medically unscathed. But several well-known musicians we had been listening to since our teens didn’t. Roll call McCoy Tyner, Wallace Roney, Onaje Allan Gumbs, Manu Dibango, Ellis Marsalis, Henry Grimes, Giuseppi Logan, Tony Allen.

A good friend from the ’90s-era Black Rock Coalition heyday, Brother K., had just retired from the MTA (Metropolitan Transit Authority) after 25 years, in December. Through his Facebook page, I learned that a high number of his colleagues were dropping precipitously from being unprotected essential workers. As a lifetime news junkie, I couldn’t not see how flagrantly disgusting our 45th president (aka Agent Orange, aka the Tangerine Mussolini, aka the Dorito) was in any way thinking about the virus that didn’t support his narrative. I also recognized that his political dissembling around the ’Rona—as many Blackfolk took to calling the virus—was ultimately going to kill more people than Covid-19 itself.

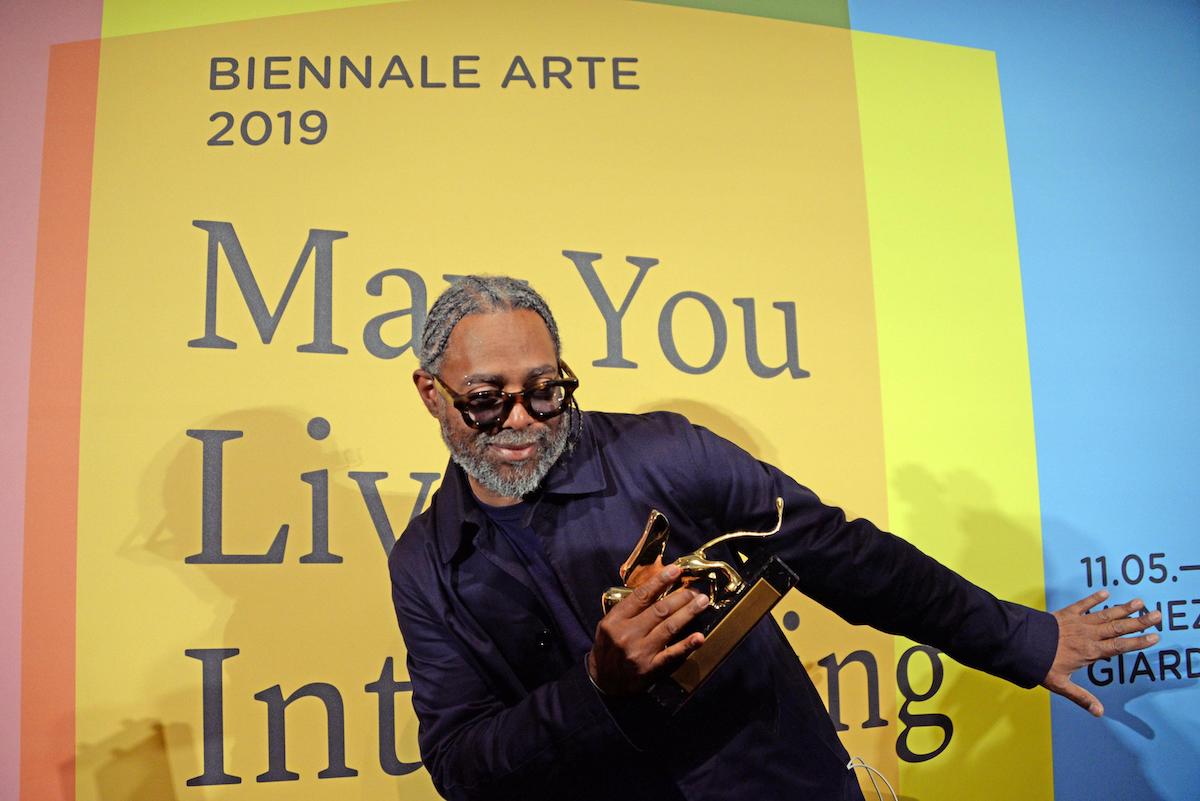

Deep Google dives into the actual science revealed that the most honest clinicians were saying they really didn’t know shit about this virus because it defied science as they knew it. Collecting strands of anecdotal information from friends about other friends’ recoveries after roller-coaster knockdown drag-out bouts with ’Rona affirmed that this was indeed nobody’s seasonal flu but instead “a species” as one friend, Arthur Jafa, put it.

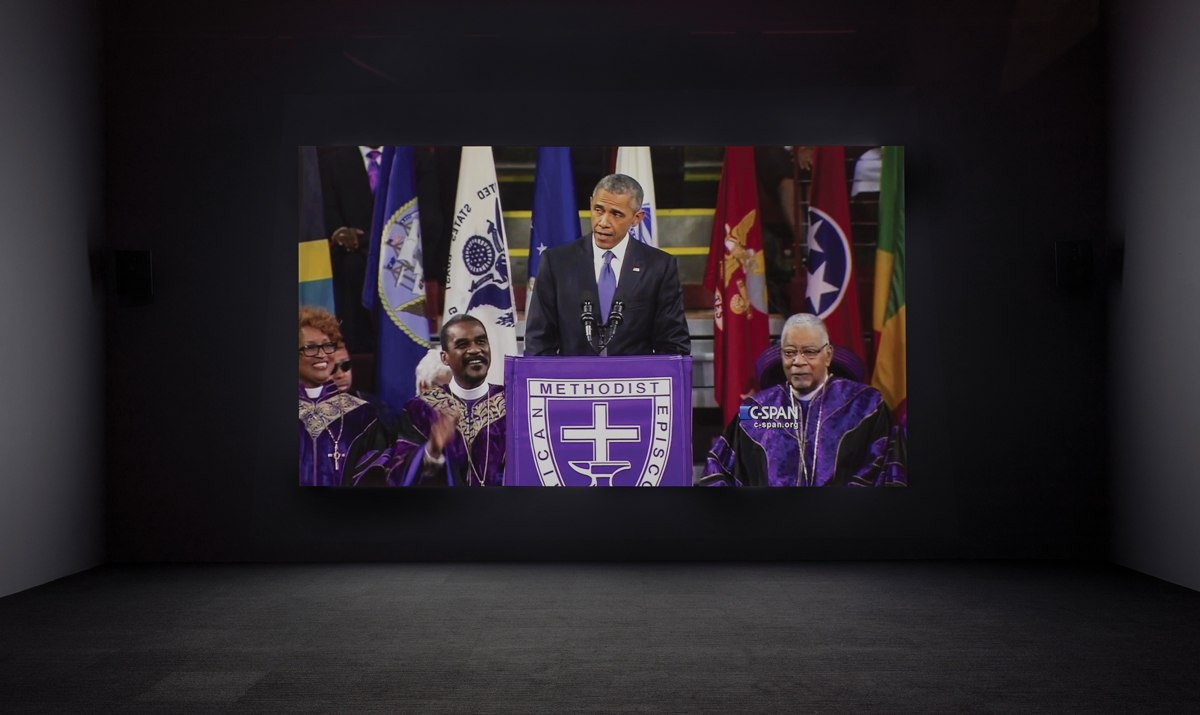

Above, view of Arthur Jafa’s video Love Is The Message, The Message Is Death, 2016, at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, 2017.

Courtesy MoCA, Los Angeles/Photo Brian Forrest

Jafa, whom I’ve known since our late-’70s Howard University days, hit me up in mid-May to show me a cut of a music video he’d just made for Kanye West’s “Wash Us in the Blood.” Formally, it was a dizzying condensed version of his breakthrough video work Love Is the Message, The Message Is Death, but the Kanye clip subtly riffed on Covid-19 as the new front of violence and plague attacking the Black community.

It would have easily been the first resonant work of public art produced for the time of the pandemic. Then, on May 25, George Floyd was killed in Minneapolis by a deputized psychopath named Derek Chauvin and all rap videos, no matter how topically or artfully done, became, like so much else of life for the next two weeks, irrelevant side notes. Whatever any of us home-alone creatives were doing in freefall got re-focused again by the mass mobilizing and volatile protests that sprang up first in Minneapolis and then in Brooklyn, Washington, D.C., and eventually hundreds of American cities in support of Black Lives Matters and an indefatigable 24-7 pursuit of justice for Floyd and Breonna Taylor and so many others.

The first days of rage were exhilarating for many of us stuck-at-home radical codgers who’d done our fair share of rallying, chanting, and protesting anti-racist mobilizations in New York in the ’80s and ’90s. We cheered the young’uns on from the safety of our shelters, railed against the administration for its storm trooper deployments, and took great satisfaction when their amassed fury got President 45 scurrying down to his White House bunker. A smell of victory in the morning was made more pungently sweet when, overnight, the Washington, D.C., Mayor Muriel Bowser got artistically and polemically inspired and had big yellow “Black Lives Matter” letters painted in the middle of Pennsylvania Avenue—turning the way to the White House into a Yellow Brick Road leading to the cowardly Tweeting tiger lurking and shirking all semblances of presidential duties in his cloistered dungeon. Even less expected was the extent to which witnessing the horrific real-time police murder of George Floyd would compel thousands of white middle-class Americans to hit the streets in their hometowns chanting Black Lives Matter and, even more remarkably, “Defund the Police”—BLM’s most radical rhetorical fireball contribution to the current election-season conversation.

Even as many of us started resettling back into our pre-protest moment mode of floating through space-time, not all were living floaty lives off the grid. For parents with kids who had to adapt to Zoom learning or, in the case of my girlfriend—a professor at a state university in California and a single mom raising a brilliant but hormone-twitchy 14-year-old—there has been no letup, no dreamy quarantine full of Netflix bingeing, no relief from the tenured academic clock. There’s instead been 12- to 14-hour days bleeding into weekends of teaching online summer courses, convening for long Zoom meetings about various administrative crises, therapeutic conferences with freaked-out colleagues and students, angry bouts with her son’s teachers about his grades and the anti-Blackness affecting them, and post-Floyd urgency on campus to design instant racial diversity correctives.

While I spent the first 120 days in my own private ether, she—and thousands like her, particularly Black women—is still pulling marathon hours handling entangled professional business and raising a Black teenage male child in a Bay Area where anti-Black policing is no less notorious than in Chicago and Baltimore or Ferguson, Missouri, and Kenosha, Wisconsin. And though we managed to get in FaceTime convos just about every night in lockdown during Midnight Diner hours, I have no idea when I’ll be feeling intrepid enough to hop on a red-eye to San Francisco. I have, however, taken the subway several times since the curve flattened, much to the chagrin of many friends who said they can’t even think about going underground again yet. Never mind that the trains are cleaner than ever, due to shutting down between 1 and 5 a.m. for fumigation. They’re scarier than ever too, in a city racked by PTSD.

A version of this article appears in the Fall 2020 issue of ARTnews, under the title “Big Apple Blues.”

Published at Wed, 09 Sep 2020 14:36:23 +0000