[ad_1]

When Quaker Oats announced that it would change the name of its Aunt Jemima syrup and pancake mix earlier this week after saying that the brand’s “origins are based on a racial stereotype,” the news was seen as an acknowledgement that the brand’s iconic image had played a role in systemic racism in the United States. But the company’s use of Aunt Jemima has long been the subject of work by Black artists who have created visions of her liberation.

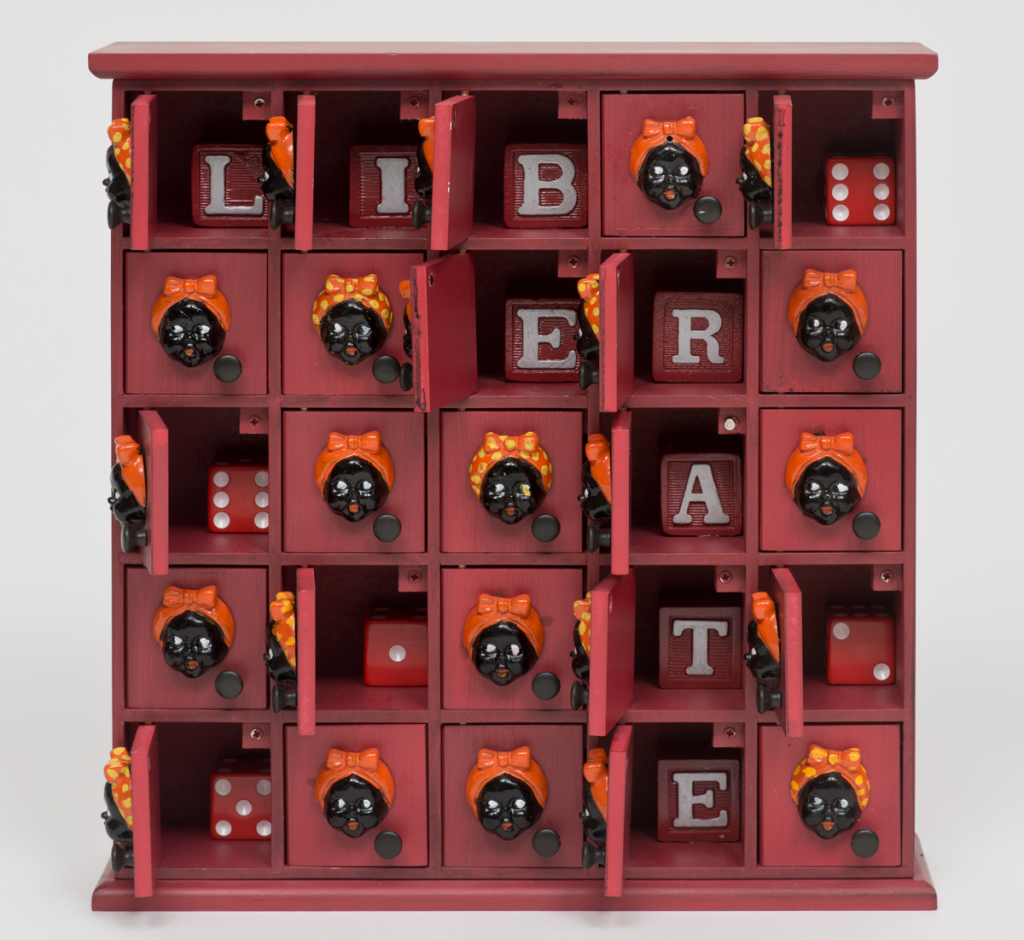

Collection of Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive, Berkeley, California, purchased with the aid of funds from the National Endowment for the Arts (selected by The Committee for the Acquisition of Afro-American Art). Courtesy the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles, California. Photo: Benjamin Blackwell

The most iconic of these works is Betye Saar’s 1972 sculptural assemblage The Liberation of Aunt Jemima, now in the collection Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive in California. In the center of the work is a ready-made figurine that shows a stereotyped mammy figure. In one hand she holds a broom and in another, a rifle. In the center of her dress, Saar has placed a small painting of Black woman smiling as she cares for a white baby with a Black Power fist superimposed over the image. The central figure stands over a bed of cotton. Behind her, Saar has tiled the image of Aunt Jemima taken from the product’s packaging.

In an email to ARTnews, Saar wrote, “My artistic practice has always been the lens through which I have seen and moved through the world around me. It continues to be an arena and medium for political protest and social activism. I created The Liberation of Aunt Jemima in 1972 for the exhibition “Black Heroes” at the Rainbow Sign Cultural Center, Berkeley, CA (1972). The show was organized around community responses to the 1968 Martin Luther King Jr. assassination. This work allowed me to channel my righteous anger at not only the great loss of MLK Jr., but at the lack of representation of black artists, especially black women artists. I transformed the derogatory image of Aunt Jemima into a female warrior figure, fighting for Black liberation and women’s rights. Fifty years later she has finally been liberated herself. And, yet more work still needs to be done.”

©Faith Ringgold/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Courtesy ACA Galleries, New York.

These days, Faith Ringgold is best known for her story quilt works; her first work in the medium, titled Who’s Afraid of Aunt Jemima? (1983) and created for her 1984 solo show at the Studio Museum in Harlem, dealt with a similar topic. That piece consists of 56 squares of juxtaposed triangles of various quilts alongside images of Black women, Black girls, Black men, and white men and women and 9 panels of text that retell and reimagine the story of Aunt Jemima.

In her memoir We Flew Over the Bridge: The Memoirs of Faith Ringgold (1995), Ringgold wrote, “I decided to create a special work for this occasion to show a future direction in my art. The idea of a painted quilt was upper most in my mind. … The Story of Jemima Blakey, the name I gave to my radical revision of the character and story of Aunt Jemima, flowed from me like blood running from a deeply cut wound. I didn’t want to write it – I had to. I was tired of hearing black people speak negatively about the image of Aunt Jemima. I knew they were referring to a big black woman and I took it personally.”

In a panel hosted by the Museum of Modern Art on June 18, Ringgold said, “I told her story. I created a complete family for her, therefore giving her a history and not just ridiculing her. … Why does Aunt Jemima have to be so nothing and so derogatory?”

Courtesy the artist

Renee Cox took on Aunt Jemima as part of her photographic series, “Rajé,” which shows the artist as a Black superhero named Rajé, the granddaughter of Nubia, the long-lost twin sister of Wonder Woman. In 1998’s Liberation of Aunt Jemima and Uncle B, Cox shows Rajé standing arm-in-arm with a freed Aunt Jemima (portrayed by supermodel Roshumba Williams) and Uncle Ben (portrayed by actor Rodney Charles) in front of their boxes.

In a phone call, Cox said, “The motivation is 400-odd years of oppression of black bodies in this country. From the beginning, I’ve always been interested in creating my own dialogue in terms of representation of Black people to break the stereotypes that have been imposed on us by a white supremacist society. I’m not into portraying Black people as victims. I wanted to change the perception.”

She considers the work only one part of a larger project. “Art, for me, is about creating a discourse to create that conversation where it can come up. Why do you have to liberate them from their boxes? Well, first of all, do they own the company? Then why are they on the box? Because some people feel safe knowing that you have a big mammy flipping flap jacks for the white family. There’s something reassuring about that. This is one small step for Black folks, but I guess it’s a giant step for white folks to take them off the boxes because it took them 130 years to take her off the box. I’ve been asking for it for 22 years and before me there were others asking for it too. It’s superficial, that’s all, so people have to bear that in mind.”

[ad_2]

Source link