Best Practices: Lu Yang’s Otherworldly Avatars Imagine New Possibilities for the Body

Five years ago, Lu Yang made a genderless rendering of himself the protagonist of Lu Yang Delusional Mandala, a 2015 video in which the artist’s avatar wears a baseball cap and dances through a computer-generated version of outer space. Not that the figure is carefree. The viewer is given to understand that there is a tumor in the avatar’s brain, and at times it seems to be in pain. At various points in the 16-minute piece, it is probed by diagnostic machines. The avatar dies and lives again numerous times, and ultimately ends up suspended in an enormous mandala.

Speaking by Zoom recently from his studio in Shanghai, Lu said that, with that video, he wanted to make a version of himself that was free of the constraints of gender and sexuality. “I really don’t like to have some label for gender placed upon myself,” he said. “I am just a human being—that’s all. When we go out, people think, ‘Oh, you’re a male, you’re a female.’ People always judge you. But actually, when we are alone, we don’t really think about who we are and what kind of gender we are. That body,” he continued, referring to his avatar, “is the perfect body for me.”

Books in Lu Yang’s studio.

Dave Tacon for ARTnews

Being alone is something Lu has come to embrace—especially during the coronavirus pandemic. In his mid-30s, he is one of the world’s most visible emerging artists, and by the time everything shut down, he’d gotten used to frequent travel. One of the foremost members of a new generation of artists working with digital technology, he has shown his work at the Venice Biennale, as well as festivals from Moscow to Istanbul; a typical year involves getting on a plane every two months. But since March he’s been confined to his two-floor studio in Shanghai. “That brings me more time to polish my work,” he said.

Lu’s work is as maximalist as art gets—it’s filled with pulsing electronic music, fast-paced edits, and colorful CGI. His studio, on the other hand, tends toward minimalism. Much of his work is done on a bank of computer monitors, where he uses digital technology to envision new bodies free from traditional Western conceptions of life and death. Above one monitor hangs a page from an old calendar showing the Hindu god Mahakala encircled in fiery red and orange flames. Mahakala is a manifestation of Shiva—an avatar not all that dissimilar to the digital ones that populate Lu’s videos.

Those videos and performances involve highly complex technology of the sort typically used to make video games and Hollywood blockbusters. Whereas many artists working with similar technology farm out the labor to firms around the world, Lu prefers to craft his art largely on his own, without assistants. “I don’t like having people sit beside me, so I work by myself. But I chat with people online,” he said. When he works, he mostly listens to J-pop. “Boy bands,” he admitted, with a laugh.

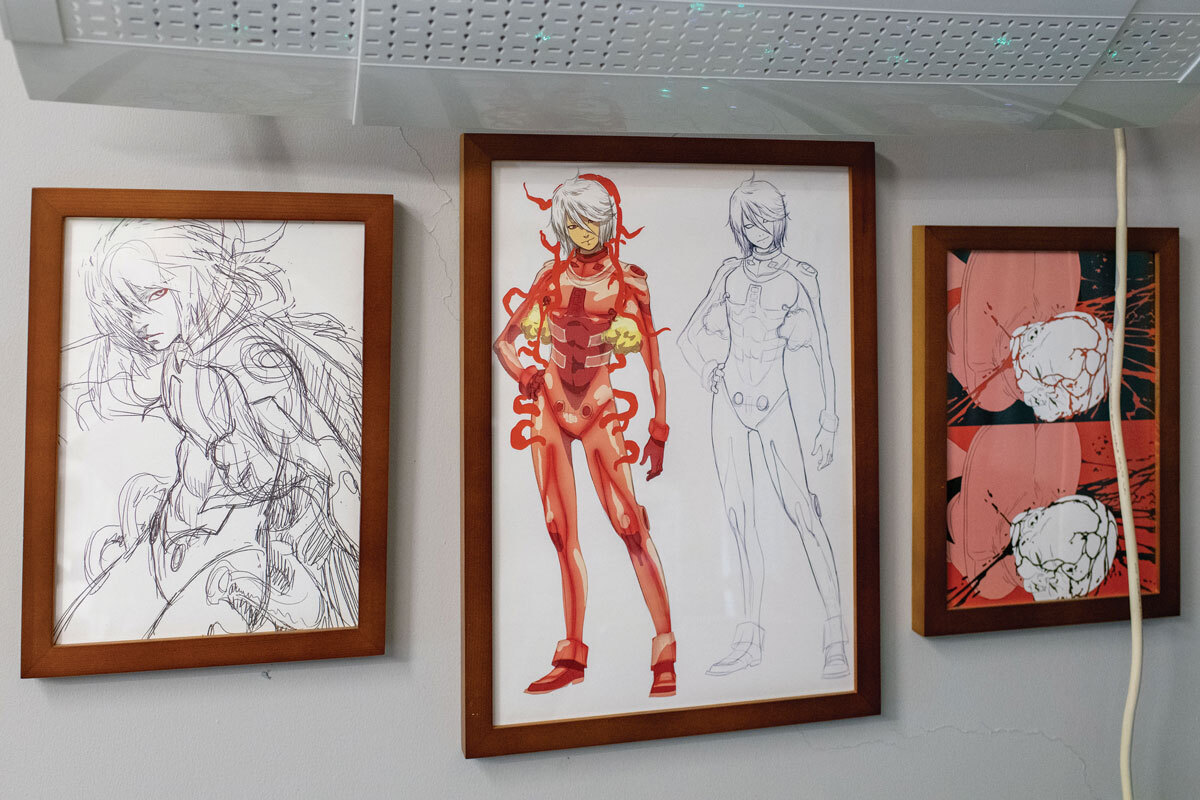

Adorning his walls are posters for video games like Final Fantasy. Heroes from that game or others from the Marvel and DC Comics universes interest Lu because the impulse to create such characters has existed from the beginnings of human history. “We always love to create a new human being,” he said. “It’s like creating a new avatar.”

Artworks and mementos in Lu’s studio.

Dave Tacon for ARTnews

From a young age, Lu was interested in worlds other than his own. Born in 1984 in Shanghai, he was attracted to his grandparents’ books on Buddhism. “During that time, I could accept everything,” he said. “I read Buddhist books for deeper meaning.” He went on to attend the vaunted China Academy of Art in Hangzhou, where he studied under artist Zhang Peili, who is known for his painstaking performances shot on video. Lu enrolled with an interest in painting, and graduated with a predilection for the newest technologies.

Lu made his first avatar in 2012—Uterus Man, a semi-human asexual superhero rendered in an anime-like style and equipped with a chariot crafted from a human pelvic bone. The latest one in a line of seven is Doku, short for Dokusho Dokushi. “In Chinese,” Lu said, “that means you are born alone and you die alone”—a reference to a Buddhist sutra. “How can we say that Doku came to the digital world alone, without other people? I don’t think he has a consciousness.”

Lu Yang in his video Lu Yang Delusional Mandala, 2015.

Courtesy Société, Berlin

Months of work went into making Doku seem as lifelike as possible. The character recently appeared in a video for the British band The 1975, where Doku is shown in an empty digital arena, chest inset with glowing lights and hands producing purplish afterimages as the figure gyrates and mouths the words to the song. Like his other avatars, this one is asexual. Doku looks uncannily like Lu, an effect he accomplished with the help of Facegood, a Shenzhen-based studio that uses motion capture technology to create digital animations. A number of dots were drawn on Lu’s face with a marker before he stepped into a device fitted with cameras that photographed his face as it moved through all its countless expressions. A computer then analyzed the images, and Lu fed them into Unity, a program typically reserved for video games.

Lu as Doku in a music video for The 1975’s song “Playing on My Mind.”

Courtesy doku2020

Doku’s dancing can be traced to animation programs like MikuMikuDance that Lu mastered in high school. “I really wanted to dance like that avatar inside that digital world,” he said. He hired professional dancers to model Doku’s moves; one of them is Kenken, a huge star in Japan. Test footage of the dancers at work shows them flinging their arms around in gridded cyberspace.

Doku has also taken on the accoutrements of celebrity, including a personal clothing stylist and a tattoo artist—Oshima Taku—who provided the avatar ink art inspired by the Jōmon people of Japan. And collaborations such as that with The 1975 won’t be the last. Doku’s next project involves teaming up with Li-Ning, a Chinese sports brand. “Doku is not like digital idols, where they just wear nice clothes,” Lu said. “We really want to set up connections.”

In the meantime, Lu is hard at work continuing to hone Doku’s aesthetic. Up next are more realistic-looking wrinkles and a new hairdo. “CGI work, you are always polishing it,” he said of his preoccupation while in quarantine. “You have to spend a lot of time polishing it, to make it more like a digital human.”

A version of this article appears in the Fall 2020 issue of ARTnews, under the title “Lu Yang Programs an Avatar.”

Published at Tue, 03 Nov 2020 15:52:37 +0000