[ad_1]

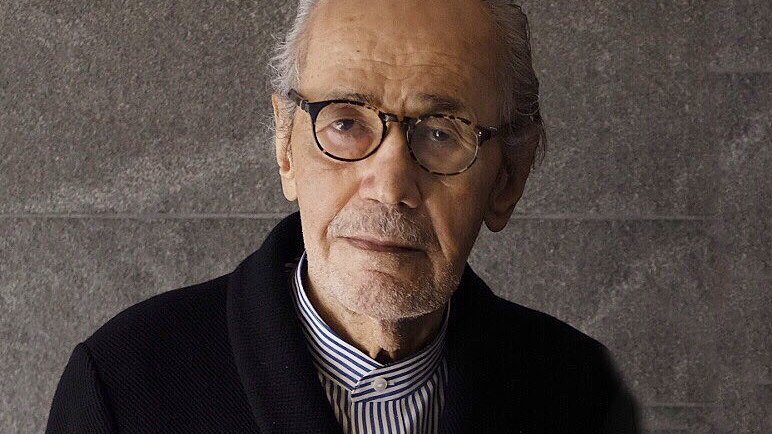

Siah Armajani, an under-known giant of contemporary art whose work in a variety of mediums attested to the power of vernacular architecture and collaborative social spaces, has died at 81. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, which staged a New York retrospective of his art co-organized with the Walker Art Center in 2019, announced the news on social media on Thursday night. ArtAsiaPacific reported that he died of heart failure.

“We are deeply saddened to hear of the passing of Siah Armajani (1939–2020), an artist known for his wry sense of humor, his gentle nature, and his deep conviction in the revolutionary potential of art as a form of civic engagement,” Clare Davies, a Met curator who organized the Breuer retrospective, said in a statement.

Armajani’s work, with its vast array of allusions and multifarious forms, is often unclassifiable, which may account for why the artist did not receive a proper museum retrospective in the United States until the Walker mounted the Minneapolis version of the show in his hometown in 2018. But Armajani’s influence was vast, and it can be glimpsed in his public artworks, which can be seen around the U.S. and often take the form of angular bridges.

Those bridges, Armajani often said, were a reflection on how structures can unite everything around them. Drawing on concepts derived from Martin Heidegger’s philosophy of being in the world, they consider how social spaces include architectural structures, nature, and the people who inhabit them. His bridges also aimed to show just how many disciplines public art draws on. “The language of public art is a hybrid language—the social sciences, architecture, and sculpture put together,” he told the New York Times in 2002.

Armajani’s work sometimes had a subtly humorous edge. Bridge Over Tree (1970) is a roofed structure that is flat, save for a sharply raised section in the middle that allows a small evergreen tree to play home beneath it. The shingling on its roof and its grey trusses recall the kind of architecture that can be glimpsed across the Midwestern U.S. Initially shown at the 1970 Walker Art Center show “9 Artists / 9 Spaces,” where environmentalists took issue with the tree beneath the bridge, the work was recently re-created by the Public Art Fund in New York’s Brooklyn Bridge Park, where it became a hit.

Christina Horsten/picture-alliance/dpa/AP Images

Armajani’s bridges have become his most iconic works. He has built them in Münster, Germany, and around Minneapolis, where has long been based. He even built one near the Staten Island Ferry terminal in New York (officials began demolishing it in 2018) and he erected a bridge-like form for the 1996 Olympics in Atlanta, where he created a trussed tower that was topped by a large red cauldron.

Armajani was omnivorous in his studies: he constantly alluded to modernist art, continental philosophy, postmodern architecture theory (Robert Venturi was particularly influential for him), scientific and mathematical concepts, and current events, often combining all of these to create works that seemed, at first glance, to have little to do with any of them. But he did not shy away from invoking difficult topics—especially political ones.

For his 2004 work Fallujah, for example, he created a large glass structure that has inside it a rocking horse, cut-outs resembling flames, and a re-creation of the hanging lamp that can be seen in Pablo Picasso’s Guernica. The sculpture, which is owned by the Walker Art Center, a longtime supporter of Armajani, is focused on the Second Battle of Fallujah, the bloodiest battle of the Iraq War, in which U.S. soldiers attempted to take control of a city led by insurgents. With its off-kilter glass structures inset in one another, the work has a dizzying, horrifying quality.

Even his bridges had a political dimension. In 1988, in Minneapolis, he created the Irene Hixon Whitney Bridge, a 375-foot-long structure that spans a 16-lane highway, uniting two communities that had long been separated by the road. Recently repainted in shades of cadmium yellow and cool blue, the bridge is adorned with lines from poetry by John Ashbery: “IT IS FAIR TO BE CROSSING / TO HAVE CROSSED,” reads one. The cadmium shade is a hue known as Jeffersonian Yellow, which Armajani prized for its connections to the Founding Father, whose Monticello home was a frequent point of fascination for the artist.

AP Photo/Tannen Maury

“One of the main colors that [Thomas] Jefferson talked about extensively in a series of letters that he wrote to his nephew is the color yellow,” Armajani said in a 1988 interview with the Walker Art Center. “And when you take that dissertation of Jefferson and put it next to [El] Lissitzky’s dissertation about Constructivist color, they are identical. Verbatim. They are both revolutionary in demanding change and identification. So that was the reason for the color.”

Siavash Armajani was born in Tehran, Iran, in 1939. His father had been a successful textile merchant and kept in his home a number of books, which left Armajani with a thirst for knowledge as a child. Early on, there were signs that he would become a maker of objects that were difficult to pin down. During one private art lesson that Armajani took, a teacher instructed the students to paint an apple—a standard art-school exercise. Armajani’s response was to cut out the form of an apple and glue it to a piece of paper. The teacher was furious, but Armajani’s father encouraged him to continue making art in this way.

Armajani’s dedication to democracy was also established during his childhood. As a teenager, he worked for the National Front, a party that, during the early 1950s, was associated in Iran with Mohammad Mossadegh, a prime minister who pushed for secular democracy and decried foreign intervention in his country. Armajani worked delivering “night letters,” pamphlets that explained the National Front’s views. In 1953, Mossadegh was overthrown in a U.K.- and U.S.-led coup, and the shah, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, who aimed to reinstate the monarchy and modernize Iran, was installed.

Following his family’s orders, Armajani departed Iran for the United States in 1960 and began studying at Macalester College in Saint Paul, Minnesota, where his uncle was a professor in the history department. Work made by Armajani in the years leading up to his emigration is a reflection on the turmoil Iran was facing at the time. It often resembles Persian manuscript pages, though the format is disturbed, with text that appears to run off the page and seal wax dribbles everywhere.

Text, for Armajani, became a common point of inquiry, as did mathematics. During the late 1960s, he began taking classes at the Control Data Institute in Minneapolis, where he learned Fortran, a computer programming language. Using nascent computer technology, he created text-based works that involved rearranging words and equations by digital means. Among the first computer works he created was Print Apple 2 (1967), in which words from the title are rearranged and set inside a fruit-like form.

Courtesy Metropolitan Museum of Art

Armajani’s art of the 1960s and ’70s paralleled experiments taking place among Conceptualists and Minimalists, who were relying on mathematical systems to dictate how artworks were made. At Kynaston McShine’s seminal 1970 Museum of Modern Art show “Information,” which also featured key works by Michael Heizer, Douglas Huebler, Rafael Ferrer, Lawrence Weiner, Hanne Darboven, and many others, Armajani showed A Number between Zero and One and North Dakota Tower (1970), which featured a nine-foot-tall stack of printouts of every digit derived from 10-205,714,079. Although “Information” is now considered a key exhibition and many of its artists’ contributions have been studied in-depth, Armajani’s pioneering computer-based works—including his films made with the technology, which were included in his 2018 retrospective—remain a lesser-known part of his oeuvre.

As the 1970s, Armajani’s work grew even more ambitious. Starting in 1974, he began creating a series called “Dictionary for Building,” for which he made ultimately more than 1,000 maquettes of architectural elements and which formed a substantial portion of his recent retrospective. “I was trying to put together an index of art and architectural possibilities, all the physical properties of doors, windows, and so forth, such as a chair against a wall, or a chair by a window,” he once said. The series, with its emphasis on classifying architecture according to various systems, dovetails neatly with similar experiments by Ed Ruscha and the photographer duo Bernd and Hilla Becher.

While Armajani’s work is not as widely known as it should be, he was occasionally given big showcases. He was included in the 1981 Whitney Biennial, the 1972 and 1982 editions of Documenta in Kassel, Germany, and in the U.S. Pavilion at the 1980 Venice Biennale, which that year focused on drawings. In 1999, the Museo Reina Sofia in Madrid mounted a survey of his work. In 2018, his work appeared at MoMA as part of a much-publicized presentation intended to protest Donald Trump’s travel ban affecting seven Muslim-majority nations.

Armajani could sometimes come off as standoffish in interviews. He hated to be photographed, and he rarely wanted to leave his studio—the longest period he ever spent away from Minneapolis after 1960, according to press reports, was six days. His work, however, was nothing short of extremely generous. He often created “Reading Rooms,” structures that contained tomes that viewers could peruse, allowing themselves to obtain all the knowledge the artist had. At the Met Breuer, Armajani invited the collective to Slavs and Tatars to oversee the library for one; their reading list mostly focused on the largely under-known history of the Black community in Russia.

On Twitter, Slavs and Tatars wrote, “He confounded expectations of identity and the narrow pigeon holes served as sides.”

[ad_2]

Source link