Slade to Zaria, which refers to the prominent art schools in London and Nigeria, is a column by Chibundu Onuzo, a novelist and fellow of the Royal Society of Literature. Every month in The Art Newspaper she shares her reflections on the contemporary art world.

Chibundu Onuzo

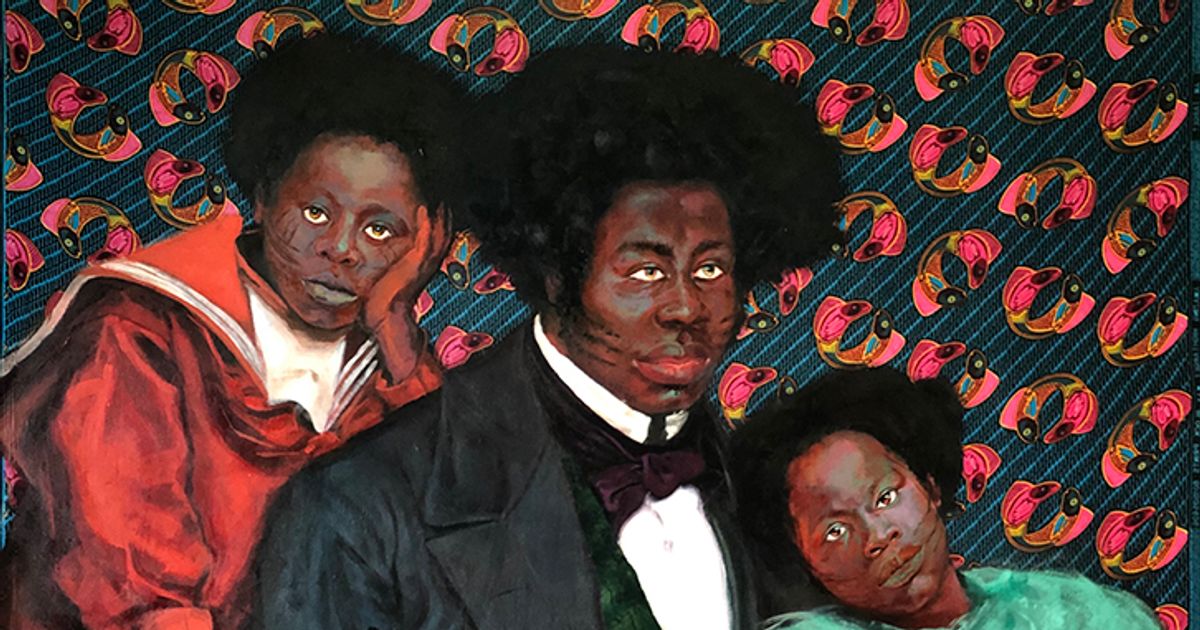

There is a life-size portrait of an African Victorian man on my landing. His name is Boda Ajani and he is impeccably dressed in a black morning coat, grey trousers and a white dress shirt. His hair is combed out in an afro and he sits in an armchair, clutching a newspaper titled Òmìnírá. Òmìnírá means “liberty” in Yoruba.

When I look at this portrait, I am reminded of the first generation of West African nationalists who embraced European ideas and technology but remained proud of their heritage, language and culture. Although Boda Ajani comes entirely from the artist, Uthman Wahaab’s, imagination, he has painted him in detail, down to the oily shine on his nose and the red rims of his eyes.

Boda Ajani gives my guests a fright whenever they go up the stairs to use the bathroom. Not everyone ‘likes’ him but they all have something to say.

“He looks like Samuel L. Jackson.” My brother-in-law.

“His eyes are scary,” says a friend unnerved by the strength Wahaab has infused into his subject’s gaze.

And the most common, “Who is he? What’s his story?”

Wahaab’s piece always provokes a reaction. Admiration, aversion, curiosity: his work always draws something from the viewer.

I started looking at art seriously in my early 20s. Before then, I avoided museums and galleries. There were few Black artists on the walls. There were few Black people in the space. And leaving the matter of race aside, I was unsure of how to respond to works of art. I felt I needed a guide, some more learned mentor to explain what it all meant.

It was a friend of mine, the artist Victor Ehikhamenor, who introduced me to looking. “Just look,” he said, “and see how you feel about a piece.” I didn’t have to know the history of Renaissance painting, Impressionism, Abstract Expressionism or any other -ism. I didn’t even need to know who the artist was. Till this day, some artists don’t sign their works. It is enough to have made the work and know that someone will look at it and respond.

Of course, knowledge around a piece does add an extra layer of appreciation. Critics and art historians are a necessary part of the ecosystem but an equally necessary part is the ordinary viewer like me, anyone willing to simply engage with the work an artist has made.

I began looking and eventually, tentatively, I began buying. My first purchase was a fabric collage by Marcellina Akpojotor. She gathered discarded and disparate textiles from dressmaker’s shops in Lagos and painstakingly pieced them together into a woman’s face. The end result was harmonious and beautiful.

Akpojotor’s work meditated on sustainability, on second chances and on transcending base origins. The piece was a unified whole made from discordant fragments. Till this day, I look at this collage when I am editing a rough draft of a novel, reminding myself that a book too can transcend base origins. Akpojotor’s practice continues to grow. Her more recent work can be seen in London at HOFA Gallery, in the Mother of Mankind group show until 31 August.

Initially, I found myself drawn to works by West African artists. The subject matter was instantly familiar. Like an early work I own by the Ghanaian master Ablade Glover. It is a painting of a market woman done in profile. There is a stillness about her, an air of the regal that I recognise from watching market women waiting for a customer. Increasingly, I also look further afield, especially at works by artists straight out of art school, like Pam Evelyn, whose use of colour makes me jump every time I see it. Evelyn has just participated in a group show at London’s The Approach gallery and is certainly one to watch.

I don’t often style myself a collector. It’s a title given to people with much deeper purses and much better connections than me. I can’t change the trajectory of an artist’s career by including them in my collection. I can’t buy multiple pieces of an artist’s work and donate one to a museum, thus increasing an artist’s status and market value. I can usually afford just one piece, sometimes only a small one. What use am I then, to a gallery keen to accelerate the career of a young artist? What is my love of an artist’s work when ranged against more powerful market forces?

There is certainly a hierarchy to collecting in a city like London and if like me, you are a young, female, black collector, you are probably somewhere near the bottom. Unless of course you are a young, black, female billionaire.

I remember travelling into central London to enquire about a painting. I wore my best coat, put on some light make-up and tried to look as affluent as possible. I actually thought I might have a chance. The artist was young and Black and reflected on immigration and the African diaspora. I too was a young, African immigrant. The artist was speaking to me. Surely my enthusiasm and deep connection to the subject matter would sway things in my favour. The work was not sold but the gallery refused to even tell me the price.

Another time I contacted a gallery to enquire about a piece I’d seen online, again by a Black artist who was receiving some media attention. I was point blank told, “We don’t sell to collectors we don’t know.” I wondered where we might have had the chance to meet? I wasn’t on the board of any museums. Should I send them my CV, I wondered? A character reference? Or perhaps I should just have invited them to lunch so we could get a chance to know each other.

Despite these rebuffs, I have still managed to gather a small collection of works I love by artists I admire. Every once in a while, I try to professionalise things. I read a book about building a cohesive art collection, about finding a focus and pruning pieces that don’t fit into your chosen narrative arc.

When this mood strikes me, I ponder what joins a still-life by emerging artist Dawn Beckles to a steel sculpture by Sokari Douglas Camp CBE. Incidentally, I technically only own three quarters of Douglas Camp’s sculpture, which I acquired from Tafeta. It is one of a few black-owned galleries in London and it runs a scheme that allows collectors to pay for work in instalments. The gallery has done a lot to increase access for young collectors like myself.

But back to the question of cohesion. What joins my collection together? Perhaps it’s too soon to tell. I’ve only been collecting for three years. I’m a mere toddler in the field. But there is one obvious answer of course. I unite my collection. It is an expression of my taste, my interests, my curiosity. I’ve let go of any anxieties about whether my taste is “good” or “bad”. It is mine. I stand by it.

Subscribe to The Art Newspaper’s digital newsletter for your daily digest of essential news, views and analysis from the international art world delivered directly to your inbox.

Find out how The Art Newspaper’s content platforms can help you reach an informed, influential body of collectors, cultural and creative professionals. For more information, contact [email protected].

Our daily newsletter contains a round-up of the stories published on our website, previews of exhibitions that are opening and more. On Fridays, we send our Editor’s picks of the top stories posted through the week. As a subscriber, you will also get live reports from leading art fairs and events, such as the Venice Biennale, plus special offers from The Art Newspaper.

You may need to add the address [email protected] to your safe list so it isn’t automatically moved to your junk folder.

You can remove yourself from the list at any time by clicking the “unsubscribe” link in the newsletter.