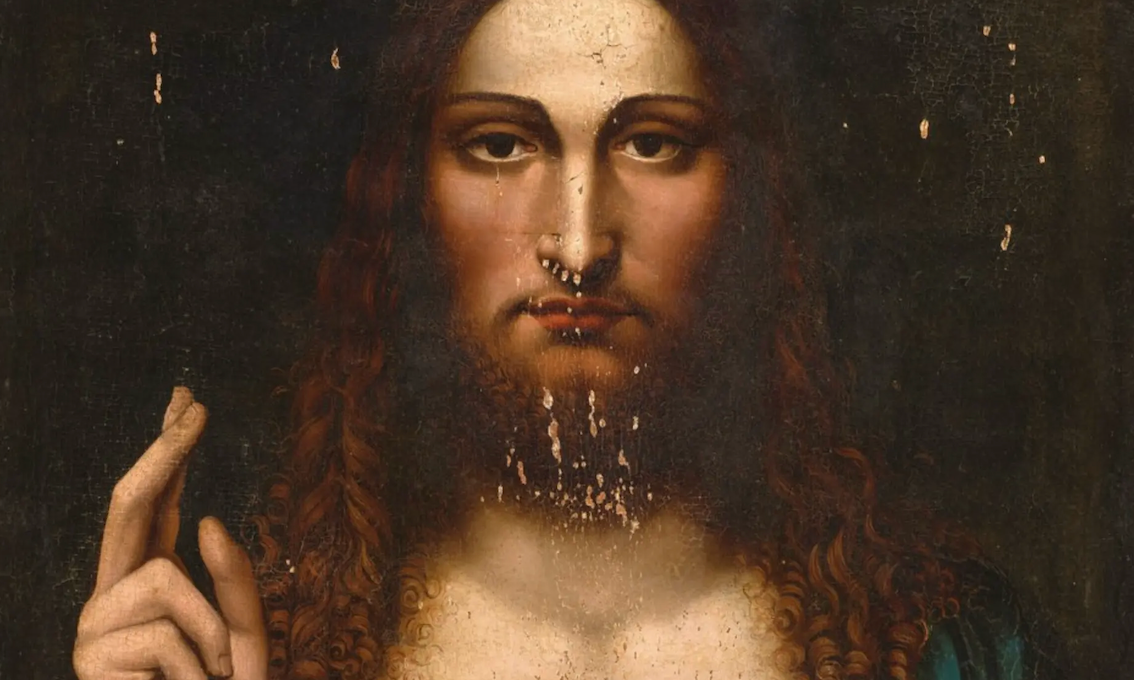

A Salvator Mundi, after Leonardo (around 1600), was sold for €1m at Christie's

Courtesy of Christie's

Diary of an art historian is a monthly blog by the British art historian, writer and broadcaster Bendor Grosvenor discussing the pressing issues facing the arts today

How much can a copy be worth? We’re used to seeing copies of the Mona Lisa—as the world’s most famous painting—fly away at auction. But thanks to a copy of Leonardo da Vinci’s Salvator Mundi making over €1m in an online Christie’s sale in Paris, we can now say that anything with even a hint of Leonardo is worth serious money. That’s quite something, for a category we are constantly told is “out of fashion”.

The picture in Paris, catalogued as a copy made almost a century after the original, had been estimated at just €10k-€15k. For a while I held the winning bid, but in the end my best effort represented a pathetic 2% of the final price. It’s a familiar feeling.

If the buyer was paying over €1m just for the image, then the Old Master market might be catching up with the contemporary market, where small matters such as who actually painted something is less important than the concept behind it. The $450m Salvator Mundi sold by Christie’s in 2017 now has big brand value.

At first glance, the Paris picture looked unexciting. Much of the drapery had flaked off, leaving patches of ground layer exposed. Christ’s face seemed too emphatically painted, as if he’d been made up for the local panto. But a higher resolution photograph revealed considerable overpaint, especially in areas around the eyes. The picture could be near contemporaneous with the original.

A crucial detail for me was the sleeve of Christ’s blessing hand. It differs from the original and nearly all known copies, which show a loose piece of fabric. Instead, it follows the sleeve seen in a drawing attributed to Leonardo in the Royal Collection, which shows one done up with a button. Another painting known today only from photographs, the so-called Yarborough copy, has the same, buttoned-up sleeve.

The Yarborough copy has recently come to wider attention thanks to a presentation by Martin Clayton at a conference dedicated to the $450m Salvator Mundi, held recently in Leipzig. Clayton suggested the different sleeve may indicate that there was another lost, original prototype, perhaps by Leonardo himself, produced in parallel.

Some might wonder if Christie’s picture is this lost, second prototype, which would be the ultimate art market plot twist: Christie’s selling one version for $450m and offering another for just €10,000. But I’m afraid the Paris picture cannot be by Leonardo.

Yet it does potentially have considerable art historical significance, if we can work out its place in the Salvator Mundi production line. I don’t believe it is merely a copy of the Yarborough picture; there are too many differences in details such as the jewels and hair. Instead, in every detail apart from the sleeve, the Paris picture is closer to the so-called Ganay copy, which has been held up by many authorities, including the Prado and the Louvre, as “a high-quality version” made in Leonardo’s workshop.

I personally find it hard to accept the Ganay picture was made in Leonardo’s workshop. It may instead have been made by the artist or artists who got hold of Leonardo’s drawings and cartoons after his death. From these, they began to make copies of Leonardo’s original Salvator Mundi, some of which reflected differences, such as the sleeve, based upon whichever drawing or cartoon they were following at the time.

The Paris picture may prove to be part of this group. If so, the winning €1m bid will have been a good bet. But I’ll keep looking for the second prototype—if it ever existed.