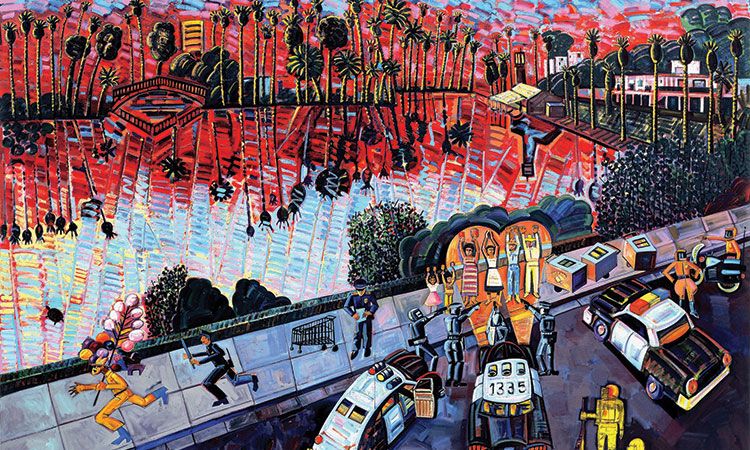

Arrest of the Palmeros (1996) by Frank Romero, a work from Cheech Marin’s collection that will go on show at the new museum.

Late in April, a 26 ft-tall lenticular image of the Aztec earth goddess Cōātlīcue was erected in the middle of downtown Riverside, California. The monumental installation by the Guadalajara-born, San Diego-based artists and brothers Einar and Jamex de la Torre is the first commission for the new $13.3m Cheech Marin Center for Chicano Art & Culture, which is affectionally nicknamed “The Cheech” and opens to the public on 18 June. If visitors look close enough, they can spot Marin’s smiling face floating in the kaleidoscopic collage of lowrider cars, wind turbines and flowers that make up the deity’s form. It is a small tribute to the actor, collector and life-long advocate of Chicano art and culture, whose 500-piece collection is now housed in the museum.

“I've been following Einar and Jamex almost since the beginning of their entrée into the art world,” Marin says. He first acquired some of their early glass sculptures and wall pieces, which he describes as “Chicano Rococo” due to their incredible detail and colour, and followed their progress as the brothers began creating lenticular works, in which images shift depending on the angle they are viewed from. A piece called Rapture, which hangs in his home, “stops visitors in their tracks”, Marin says.

The work installed at the entrance of the museum is equally arresting. It draws on the history and geography of the Inland Empire, an industrial and agricultural metropolis that lies directly east of Los Angeles, where Riverside is the largest city. As well as an ode to its new home, the installation aims to serve as a warning about the climate crisis. “We see [Cōātlīcue] beckoning us back to a simpler life, using less resources and eventually living in harmony with nature,” Jamex de la Torre says in a statement. “We see technology as the only way out of the global warming debacle.”

The museum also opens with a special exhibition dedicated to the siblings, titled Collidoscope: de la Torre Brothers Retro-Perspective and organised in cooperation with the Smithsonian’s new National Museum of the American Latino, which is still in the process of building its own home in Washington, DC. Compared to that museum project—which was first proposed 30 years ago, approved by Congress in 2020 and likely still at least a decade away from completion—The Cheech has come together in just five years. “Everybody that I talk to in the museum world says, ‘You guys are going at warp speed,’” Marin says.

Part of that is because The Cheech has occupied an existing building. Previously the Riverside Public Library, the building has been renovated by the architects Page & Turnbull and the design firm WHY. But perhaps more important is the backing the institution has received from the local community almost since its inception, according to the museum’s artistic director María Esther Fernández. “I have been blown away by the cross section of support for the Riverside Art Museum and for The Cheech,” she says. “That kind of coalition from very grassroots community organizations, all the way through to government, has just been really overwhelming and inspiring. Whether your political leanings are more liberal or conservative, I think there's just this appreciation for the arts that runs across the community.”

The seven-person Riverside city council voted 4-0 in favour of the project in January 2021, with two members recusing themselves because they had property near the museum. One voiced concern about the cost of the museum during a time of financial challenges, but abstained from the vote as a “gesture of good faith” because he wanted Marin’s “fabulous” collection to come to the city. The council also agreed to provide $1m a year for the new museum, which will cover most of its annual $1.25m operational budget.

Fernández plans to repay that support by developing programmes and initiatives that directly engage the community. In addition to special exhibitions and a permanent collection, the Cheech has a space devoted to showing work by local artists at all levels, called the Altura Community Gallery. The programme there will be run by Cosme Cordoba, a local artist and community arts organiser who owns the Division 9 Gallery and co-founded the Riverside Art Walk. “As a center that is functioning both as a museum under the umbrella of the Riverside Art Museum, and in the tradition and legacy, hopefully, of the Chicano artwork that came out the movement, this is an important part of our curatorial program,” Fernández says.

The Cheech also plans to have a film department that will be run by the San Antonio director Robert Rodriguez, whom Marin has worked with on several films, including Desperado. “We kept adding on all these aspects,” Marin says. “But, we can handle it, and we can be very successful with it. We have a place where everybody can learn all aspects of Chicano art and American art, because my motto has been Chicano art is American art.”