[ad_1]

Arthur Jafa, Love Is The Message, The Message Is Death, 2016.

COLLECTION MUSEUM OF CONTEMPORARY ART CHICAGO, ANONYMOUS GIFT TO THE MUSEUM OF CONTEMPORARY ART CHICAGO AND THE STEDELIJK MUSEUM AMSTERDAM. IMAGES COURTESY ARTHUR JAFA AND GAVIN BROWN’S ENTERPRISE, NEW YORK/ROME

Lateria Wooten, a Black woman dressed in a white, two-piece satin ensemble stands before a crowd of worshippers in a Detroit church. She sings, “What can wash away my sins? / What can make me whole again? / Oh nothing but the blood of Jesus.” Gospel composer Thomas Whitfield plays the piano while simultaneously gesturing the choir into a harmonious crescendo. Cameras capture the congregation members’ reactions to the run and rise of her vocals. Her presence commands the crowd, inciting excitement and confusion. Sweat gleams from her forehead as she thrusts her arms exaggeratedly, belting notes from her core and marching the stage in pure ecstasy. By the climax of the song, she has completely surrendered herself to the spirit, and everyone in the audience has risen to their feet. She concludes her solo with a firm “Hallelujah,” and proceeds to the very back row of the choir.

Renowned cinematographer and artist Arthur Jafa incorporates several excerpts of Wooten’s captivating performance in his 7-minute, single-channel video Love Is the Message, the Message Is Death (2016). Capturing the, as he’s put it, “power, beauty, and alienation” of Black music through a rapid-fire compilation of images, the video is a multi-layered American time capsule and the centerpiece of “Prisoner of Love,” a rotating three-chapter exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago organized by its senior curator, Naomi Beckwith.

Beckwith has placed Jafa’s seminal video, a recent MCA acquisition, in chorus with collection works by an all-star lineup of contemporary artists, including Lynda Benglis, David Hammons, Bruce Nauman, and Glenn Ligon, whose 1992 text painting Untitled (Study #1 for Prisoner of Love) provides the show’s title. The pieces by those artists have been on view for the full run of the show, which continues through October 20, accompanied by tautly organized temporary displays that have lasted for two to three months at a time, each dedicated to one dyad in Nauman’s neon sculpture Life, Death, Love, Hate, Pleasure, Pain (1983).

Installation view of “Prisoner of Love” at the MCA Chicago, January 26–October 27, 2019.

PHOTO: NATHAN KEAY/© MCA CHICAGO

In Love Is the Message, Jafa moves through American history with a pulsating sequence of images. He deploys the sampling and mixing elements of hip-hop in assembling historical and pop-cultural footage: a massive crowd of Black youth swag surfin; Akua Njeri the day after the assassination of her fiancé Fred Hampton; D.W. Griffith’s racist film The Birth of a Nation (1915); Floyd Mayweather and Southern University’s Human Jukebox; Meeka Prodigy serving body at a ball; Martine Syms sharing her Mundane Afrofuturist Manifesto, Serena Williams crip walking on the court during the 2012 Olympics; hood prophets Notorious B.I.G and Malcolm X spreading the good word. Celebratory moments like footage from a family wedding reception and Beyoncé dancing on her penthouse balcony are interrupted by clips of white policemen using excessive force to dominate and contain Black life in Ferguson, McKinney, and elsewhere.

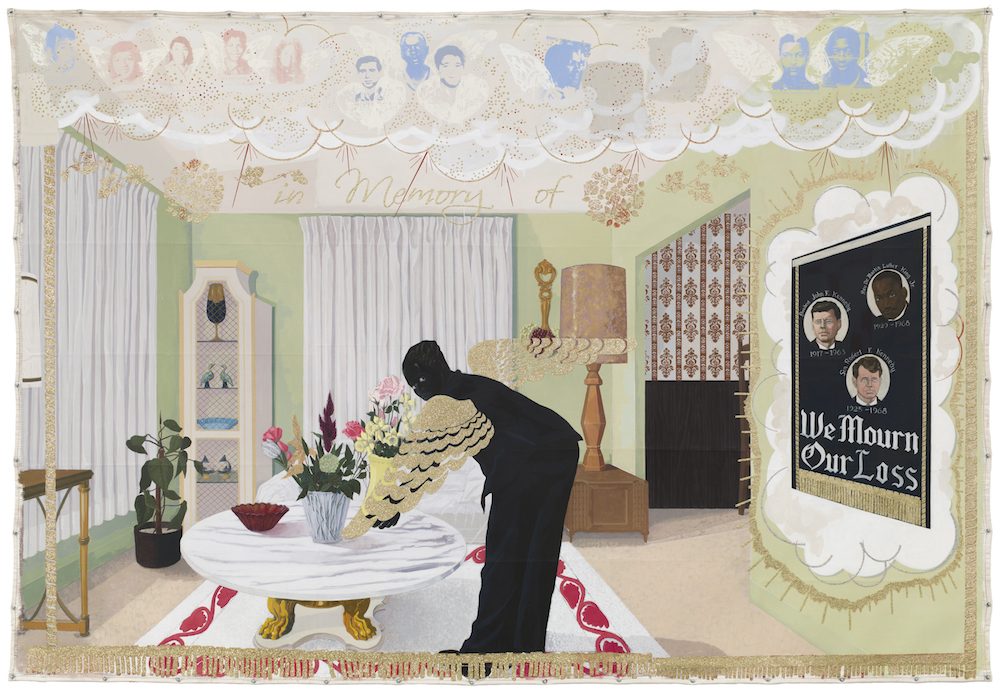

As the video is projected onto a massive wall, the thundering bass and soaring gospel rhythms of Kanye West’s “Ultralight Beam” spill into the surrounding galleries. In the first and strongest chapter of the exhibition, Kerry James Marshall’s painting Souvenir I (1997) speaks to the central themes of life and death (the section’s title). An ebony angel tends to a meticulously well-preserved Black middle-class living room, where a plastic cover protects the sofa and gold flocking adorns the walls. A memorial commemorating the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and the Kennedy brothers hangs below clouds filled with portraits of other slain figures in the civil rights movement.

Deana Lawson, Sons of Cush, 2016.

COLLECTION MUSEUM OF CONTEMPORARY ART CHICAGO, RESTRICTED GIFT OF EMERGE. COURTESY OF THE ARTIST AND RHONA HOFFMAN GALLERY

The second chapter, “Love and Hate,” included among its artists Jasper Johns, Mark Bradford, and Deana Lawson, whose enigmatic photograph Sons of Cush (2016) captures the tenderness of a young, shirtless man holding a baby in a living room cluttered with framed portraits, gold chains, and a wad of cash held by an anonymous sitter. A longtime friend of Jafa, Lawson makes evocative and highly constructed images that privilege the Black body and forefront the dignity of her subjects. Both Marshall and Lawson highlight the living room as the central, private site of the Black American psyche. In a 2013 essay entitled “The New Negro Genre Scene,” art historian and university leader Kymberly N. Pinder teases out the impact of these types of images:

“Black tragedy is at home in the African-American interior, which has become both a refuge and a shrine to living and dead ancestors. . . . Like any socially disenfranchised group, the home becomes the only site of autonomy and control. . . . All of these interiors, these stages, communicate a sense of dignity and self-projection within a space specific to class and race—and it is within that specificity that their power lays.”

By drawing parallels between 1968 and the present day, Marshall’s requiem of the civil rights era intensifies the scale and gravity of Jafa’s video. Hearing the transcendent soundscape of “Ultralight Beam” and seeing Jafa’s flurry of familiar imagery transported me back to 2016 and a moment of grief in my own home. Mindlessly scrolling Twitter at 2 in the morning, I stumbled upon leaked footage of Alton Sterling’s murder in Baton Rouge. Only 24 hours after a Facebook Livestream of Philando Castile’s death in a St. Paul suburb went viral, I held myself on the living room floor, suffocated by panic and terror. Along with the subsequent deaths of 49 Black and brown queer Pulse nightclub shooting victims in Orlando, that year marked a turning point in American society. The severely neglected racial tensions reached a boiling point and could no longer be ignored by the white majority. What had been a reality to Black Americans for centuries was all of a sudden being rendered visible.

Kerry James Marshall, Souvenir I, 1997.

COLLECTION MUSEUM OF CONTEMPORARY ART CHICAGO, BERNICE AND KENNETH NEWBERGER FUND. © 1997 KERRY JAMES MARSHALL PHOTO: NATHAN KEAY, © MCA CHICAGO

The history-making albums released that year, from artists like Solange, Kendrick Lamar, Beyoncé, and Blood Orange, have helped contextualize the overwhelming trauma of Black death and serve as testimony of Black musical expression as both a personal and collective vessel for catharsis. Love Is the Message exemplifies Jafa’s investment in making films that feel like Black music—undoubtedly America’s biggest cultural export of the 20th century, with an impact that continues to define popular culture today. The video, which made its debut at Gavin Brown’s Enterprise in New York just two days after the 2016 presidential election, resonates with a generation of Black youth who are constantly bombarded with images of Black death via social media and the internet.

In the exhibition’s final chapter, “Pleasure and Pain,” more works by Jafa come to the fore. One sculpture reproduces a highly circulated photograph from 1863 of a former American slave named Gordon sitting with his scourged back to the viewer. Adjacent to Jafa’s study of Gordon’s brutal disfiguration is LeRage (2017), a printed cut-out of a liquidy black Incredible Hulk smashing his monstrous fist into the ground. By replacing the comic hero’s iconic green, Jafa toys with mass media’s fantasies of Black male aggression. While the Hulk’s superhuman strength recalls the fear of rebellion that has permeated the white imagination since slavery, Gordon embodies the legacy of Black survival. These works reverberate the lessons of Love Is the Message, highlighting the external forces that have shaped the Black experience in America.

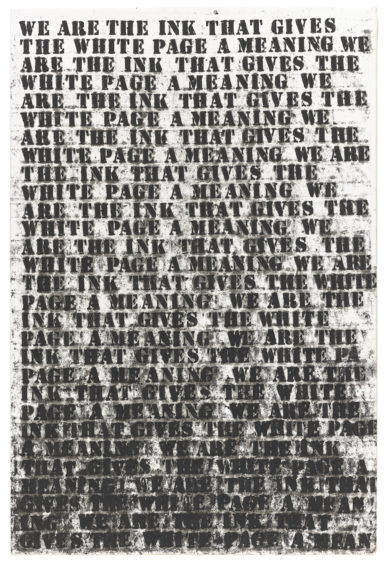

Glenn Ligon, Untitled (Study #1 for Prisoner of Love), 1992.

COLLECTION MUSEUM OF CONTEMPORARY ART CHICAGO, GIFT OF SANDRA P. AND JACK GUTHMAN. © 1992 GLENN LIGON PHOTO: NATHAN KEAY/© MCA CHICAGO

At the MCA, Jafa’s video elicits a call and response between the changing artworks in its orbit, allowing for its meaning to be expanded, revised, and reimagined. Ligon’s repetition of French writer Jean Genet’s metaphorical sentiment about Black America— “We are the ink that gives the white page a meaning”—echoes actress and activist Amandla Stenberg’s burning question, “What would America be like if we loved Black people as much as we love Black culture?” Beckwith’s critical selection amplifies that question, while also alluding to the deeply personal intersections between many of the featured artists.

Collection shows rarely get the attention they deserve, but it is particularly important that “Prisoner of Love” does not go overlooked. Its inventive format offered a promising new model for displaying permanent collections—in a way that is both formally and thematically incisive. Most importantly, though, and this remains rare in U.S. art museums, it offers a vital space for confronting our nation’s complex engagement with Blackness.

[ad_2]

Source link