[ad_1]

A visitor at the 2019 edition of the Photography Show.

COURTESY AIPAD

Alighting on Pier 94 on Manhattan’s West Side for the third year in a row, after a long run at the Park Avenue Armory, the Photography Show put on by the Association of International Photography Art Dealers appears to be hitting its stride in the new locale.

The mood at the VIP opening of its 39th edition on Wednesday was buoyant, and while the aisles were busy, it didn’t feel crowded, thanks to the decision by AIPAD’s organizers to downsize slightly, cutting the number of special exhibitions from three last year to just one and pushing booths slightly to the sides of the pier, so that photography aficionados can now see all the way down its length. (Some 94 exhibitors are showing at the fair this year—roughly the same amount as 2018’s edition.) It’s been “a matter of figuring out what works at the pier,” AIPAD’s president, Richard Moore, said.

Judging by visitor totals, the fair’s opening was a success. By end of Wednesday, AIPAD said it had welcomed more than 2,000 people, the most it had ever had on the first day.

Serenaded by the sounds of birds roosting in the rafters near the check-in tables, Throckmorton Fine Art’s director of photography, Norberto Rivera, raved about his sizable booth’s position between the entrance and coat check. “We see everyone when they come in and when they’re leaving they come in for one last look,” he said. Somebody had already agreed to buy Mexican photographer Graciela Iturbide’s famous 1979 photo Nuestra señora de las iguanas/Our Lady of the Iguanas, Mexico, in which a woman poses for the camera with a crown crafted from living iguanas, for $15,000. The gallery also brought with it three Nickolas Muray color photos of Frida Kahlo, the subject of an exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum, which it sold ahead of the preview for a combined $35,500.

Ivan Forde, Vessel I, 2018.

COURTESY THE ARTIST AND DE SOTO GALLERY

Next door, Chicago gallery Stephen Daiter is showing tenebrous scenes from Dawoud Bey’s new body of work “Night Coming Tenderly, Black,” which is being exhibited in New York for the first time. Commissioned by FRONT International: Cleveland Triennial for Contemporary Art, the photographs are low-light images of former stations on the Underground Railroad. As the work was being hung, editions of Untitled #2 (Trees & Farmhouse), Untitled #12 (The Marsh), and Untitled #4 (Leaves and Porch), all from 2017, sold—the first two went for $20,000 each, the third for $30,000.

Sales continued apace at booths of newer faces at the fair. One of these is Venice, California’s De Soto Gallery, which has been exhibiting on and off at AIPAD for around five years. This year, De Soto devoted its booth to the work of Ivan Forde, a Guyana-born photographer who makes large-scale cyanotypes that resemble mixes between collages and monochromatic paintings. The artist’s Vessel 1 (2018) was made by overlaying cyanotypes showing him herding cattle onto a image of an amphora, painted on archival paper using a photosensitive solution. Within the early hours of the fair, the work had sold for $7,500.

Arnika Dawkins Gallery from Atlanta, which is exhibiting in a full-sized booth for the first time this year, brought with it a trio of massive, unframed portraits, each of them stained, smeared and stepped on, from the series “#InHonor” by Ervin A. Johnson. Arnika Dawkins, the gallery’s founder, said the artist “used solvents to renegotiate the ink in the photograph[ic prints] and then various archival acrylic mediums—spray paint, paint, ink, etc.—to reimagine the images.” The work pays homage to lives lost through race-related violence. Also on view at her gallery’s booth are works by Delphine Diallo, a self-described “visual activist,” who is showing a series of portraits that include models wearing African-style masks made of braided hair extensions.

Also new at the fair this year is a section that extends onto the part of the pier that projects into the Hudson—a series of 23 project spaces meant for focused exhibitions. In Toronto-based Stephen Bulger Gallery’s space, large C-prints by Meryl McMaster show a figure with a painted face standing or walking through a prairie landscape at golden hour and looking solemn. In one image the figure, wearing a cornucopia-like hat with two perching birds, carries what looks like a burning basket on her back; in another she holds a miniature rowboat on her shoulder that’s full of birds, both starlings and crows. In these works, McMaster is incisively exploring her mixed Plains Cree and European ancestry, and collectors have responded—two of the photographs sold for $15,500 each.

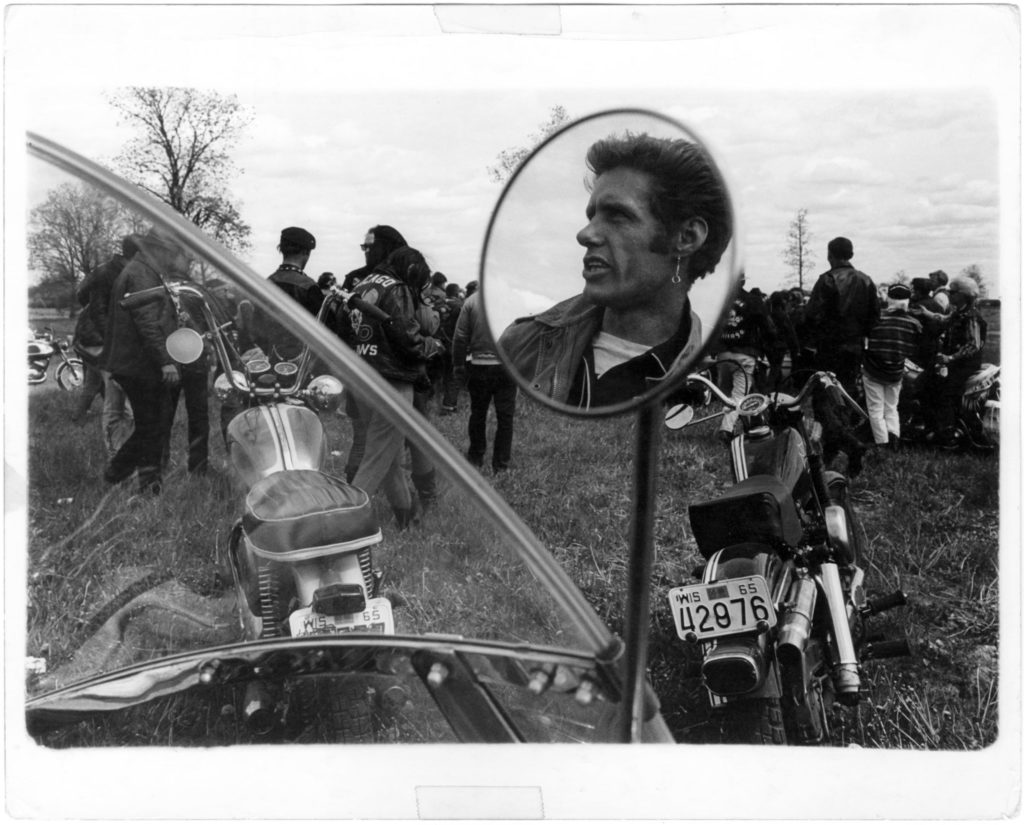

Danny Lyon, Cal, Elkhorn, Wisconsin, 1966.

©DANNY LYON/MAGNUM PHOTOS/COURTESY ETHERTON GALLERY, TUCSON

Alongside the eye-catching contemporary work on view, canonical pieces—the mostly small, framed, and black-and-white images that are a hallmark of the fair—remained attractive to collectors. In AIPAD president Richard Moore’s booth, works by Peter Sekaer, Dorothea Lange, and Barbara Morgan, ranging in price from $7,500 to $15,000, had either sold or were on reserve, most of them going to museums or other institutions. Several works from documentary photographer Danny Lyon’s famous “Bikeriders” and “Conversations with the Dead” series from the 1960s and ’70s—about life in Texas prisons and American biker culture, respectively—were on reserve for prices ranging from $16,000 to $25,000 at Etherton Gallery (the gallery was also offering portfolios of Lyon’s work, which the gallery’s director Hannah Glasston said was drawing interest from museums).

More high-profile photography could be found at an Alec Soth–curated exhibition nearby. Titled “A Room for Solace: An Exhibition of Domestic Interiors,” the show comprises 42 photos submitted by galleries exhibiting at the fair and also focused primarily on the canon. It includes work by Robert Mapplethorpe, Diane Arbus, Harry Callahan, Lange, and many others. An interesting “inside photography subtheme,” as Soth put it, could be detected within the exhibition, in that several photos either showed or in some way related to the life of Robert Frank. But in images such as Elliott Erwitt’s photo of Frank dancing with his wife and Walker Evans’s Mary Frank’s Bedroom, New York, 1959, a softer side of the hardboiled street photographer is on display. It’s “the road photographer at home,” Soth said, musing during the run-up to the fair’s opening. To Soth, the most tender photo in “A Room for Solace” is an untitled 1940s work shot by Wayne Miller for Magnum that depicts two figures on a bed caught in a moment of contemplative stillness. “There’s something about seeing the human being that’s really affirming in these divisive times,” he said.

[ad_2]

Source link