[ad_1]

LaToya Ruby Frazier, Mindy Miller standing with fellow Auto Warehouse Company ironworkers and the last Cruze in the GM Lordstown Plant Complex at 2300 Hallock-Young Road (11 years in at AWC), Lordstown OH, from “The Last Cruze,” 2019.

COURTESY THE ARTIST

Last November, workers at a General Motors plant in Lordstown, Ohio, received some fateful news: the automotive company’s chief executive, Mary Barra, had decided to “unallocate” the 53-year-old factory in town, in addition to four others in North America. Through the decision—and the use of vague language—GM would essentially close the plants while avoiding a breach of contract with United Auto Workers, a union that represents 49,000 GM employees. Production of the Lordstown factory’s sole product, the Chevrolet Cruze, was supposed to continue through 2021, but the last one was rolled out in March. Since then, the plant has been inactive, and 1,500 workers have had their lives upended.

The national media has fixated on the Lordstown factory’s shutdown in relation to Donald Trump’s response to it and the ways it could impact the political leanings of Rust Belt voters during the 2020 Presidential election. But one artist is determined to tell a different story—that of the largely unreported narrative of individual lives put on hold by a decision that left so many alone and out of work.

On a frigid afternoon last March, LaToya Ruby Frazier was taking photographs some 1,500 feet in the air above the Lordstown General Motors complex. Strapped into a helicopter, she carefully trained her heavy 600-millimeter lens on her mark below: a white Chevrolet Cruze surrounded by workers from the Auto Warehousing Company waving signs. The largest of the signs, dense with signatures, read in bold letters, “THE LAST CRUZE.”

“When I saw the news, I was moved because I understood the calamity that this was going to create,” Frazier told ARTnews months later. “I knew they were going to reduce these workers to statistics based on shares and stocks, and no one was going to pay attention to their livelihood.”

It was a calamity she had been tracking in real time. Shortly after the news about the factory was first announced, Frazier reached out to the New York Times to ask if she could partner with its newsroom to cover the developing story. Two months later, she sat outside a Lordstown union hall, waiting while members of UAW Local 1112 voted to allow her in, with her camera in tow. The decision in her favor was unanimous.

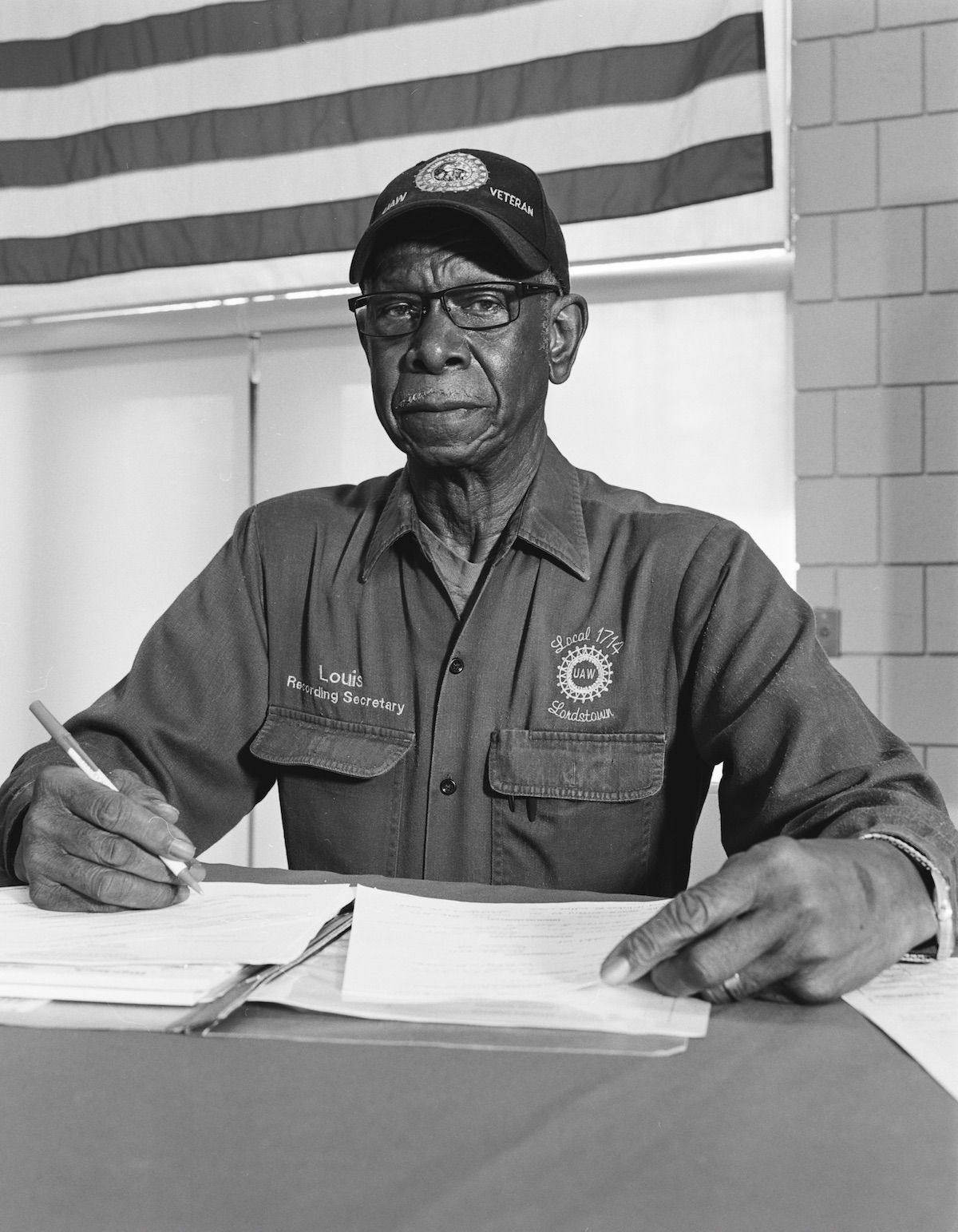

LaToya Ruby Frazier, Louis Robinson Jr., Local 1714 Recording Secretary, at UAW Local 1112 Reuther, Scandy, Alli union hall (retiree, 34 years in at GM Lordstown Assembly, die setter), Lordstown OH, from “The Last Cruze,” 2019.

COURTESY THE ARTIST

Frazier’s work in the past has often bridged the gap between journalism and art, drawing on the legacies of documentary and conceptual photography to create moving, truthful works about such subjects as the water crisis in Flint, Michigan, and her own family. She often conducts extensive interviews, and she aims to create images that are, to some degree, informational. But while her tactics are similar to those of reporters, she hopes her work complements the rapid news cycle with new, previously untold narratives—something she accomplishes through long-term, sustained collaborations with the people who appear before her lens. “Once I turn my camera on something,” she said, “I stay for many years.”

From her home in Chicago, where she teaches at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, Frazier has kept in close communication with GM workers as they have attempted to bargain with the automaker to reactivate the “unallocated” factory. She is not allowed in the plant itself—by the time she was flying over it in March, she had already been told twice that she was trespassing. According to Frazier, GM had even threatened to shoot her if she crossed the property line again. (GM did not respond to a request for comment from ARTnews.) Instead, she traveled often and stationed herself at the union hall to build relationships with the workers.

For Frazier, the plant’s fate amounts to more than just jobs—it could also cause a historic loss of heritage. “Multiple generations pass through this plant,” she said. “This is the last thing that was really the bedrock of this region, considering the closure of Sheet and Tube [an important factory in nearby Youngstown, Ohio] and the downsizing or disappearance of all the steel mills.”

After months in the making, Frazier’s new body of work relating to Lordstown debuted last weekend at the Renaissance Society in Chicago, where an exhibition titled “The Last Cruze” opened on Saturday, hours before a four-year contract between GM and UAW expired. The show (on view through December 1) features more than 60 black-and-white images shot on medium-format film, most of them portraits of union members and their families, and many accompanied by text panels featuring lengthy excerpts from hours-long interviews Frazier conducted with her subjects (some of whom attended the show’s opening as honored guests). The result is an intimate and unflinching representation of working-class Americans that signals the roiling effects of the factory’s halt through their images and their own words.

LaToya Ruby Frazier, Kesha Scales hugging Beverly Williams in her living room (22 years in at GM Lordstown Assembly, pressroom), Youngstown OH, from “The Last Cruze,” 2019.

COURTESY THE ARTIST

‘They put us in purgatory”—this was one of the most poignant sentences Frazier heard as she interviewed workers in Lordstown. The speaker, David Green, was the president of UAW Local 112 until mid-August, when he resigned after transferring to a GM facility in Indiana. He was one of many workers who had received a “force letter” from GM, which offers a choice between being relocated to a far-off facility, where one can retain benefits and pensions, or becoming jobless.

Commentaries from Frazier’s interviews are laden with emotions that range from outrage to confusion. They make clear that at the heart of the ordeal in Lordstown is a concern for family stability—“family” meaning blood relatives as well as coworkers who have long considered each other brothers and sisters. Frazier’s portraits are elegiac and suffused with stillness: a father surrounded by his wife and children in their newly built house; a teenager, fearful about moving to Tennessee, standing tall with her best friend; a tense meeting of three different generations around a kitchen table. The last image, showing the power of domestic settings for families who live within them, could be seen as a nod to the iconic “Kitchen Table Series” by one of Frazier’s mentors, Carrie Mae Weems.

Frazier considers “The Last Cruze” as a monument to the workers she came to know. In lieu of typical frames, her photographs are mounted on 21 orange armatures that are scale-size replicas of factory brackets that once held Cruzes as they went through the assembly line. The windows in the Renaissance Society have been blacked out, to mimic sunless factory rooms. But Frazier speaks of the show’s installation in terms that transcend the factory, too. “It’s like a sanctuary,” she said of a setting accentuated by the Renaissance Society’s high ceilings and sloping walls, which have been painted General Motors Blue.

To make the orange brackets that surround her pictures, Frazier referred to photographs by Kasey King, an autoworker who also served as UAW Local 1112’s documentarian and editor. King became “a real photo buddy,” Frazier said, and in tribute, she included a 58-minute video by King that takes viewers on a tour through the entire factory. “Most people don’t realize it, but I’m always commemorating and nodding to a working-class person that is an artist,” said Frazier, who herself grew up in a steel town (Braddock, Pennsylvania, whose economic decline she chronicled in her book The Notion of Family). “I fundamentally believe that anyone who has ever worked in a factory is an artist, because they know how to create with their hands.”

In addition to amplifying the voices of workers in Lordstown, Frazier has created a timeline of the United Auto Workers union’s history in a booklet that visitors to her exhibition can take home. It shows how UAW has long been at the forefront of social progress, particularly under the leadership of Walter Reuther, the famed workers’ rights advocate who served as the union’s president from 1946 to 1970. UAW was the first union to hold a Women’s Conference, in 1944, and it was also involved in the civil rights movement in the ’50s as well as the Farm Workers’ movement in the ’60s. More recently, in 2018, UAW represented employees at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, helping them secure a five-year contract that includes wage increases.

“Once you see what I reveal about their history, you’ll understand why conservative Republican leaders always attack the UAW,” Frazier said. “The sad thing is, our own citizens don’t realize that this is the most progressive, radical union to ever exist.”

LaToya Ruby Frazier, Mindy Miller standing with fellow Auto Warehouse Company ironworkers and the last Cruze in the GM Lordstown Plant Complex at 2300 Hallock-Young Road (11 years in at AWC), Lordstown OH, from “The Last Cruze,” 2019.

COURTESY THE ARTIST

The UAW is also a union whose members pride themselves on their craft. After Frazier photographed the last Chevrolet Cruze to roll out of the Lordstown factory in March, John Davies, Jr., who had worked there for 12 years, told her, “This is our legacy here. This is our product.”

The final Chevy Cruze had been destined for the distant roads of Florida, but when union leaders found out it was leaving the state, they called up local dealers and managed to negotiate to reroute the car to Boardman, Ohio. When it finally arrived at Sweeney Chevrolet, it had been marked up with unconventional embellishments: signatures of Lordstown workers left in marker on the front fenders, door hinges, and the undercarriage. In the trunk were signs that read “We are USA strong” and “We will survive.”

This past Sunday, the day after the Renaissance Society show opened, the UAW voted unanimously to go on a national strike against GM when negotiations broke down and the union’s contract expired. It is the first such strike against the automaker in 12 years, with nearly 50,000 workers in nine states walking off the job. Frazier said she will continue to follow the actions of the workers, and she urges her audience to keep up to speed. As part of her exhibition, she has organized panel discussions with UAW chapters and the UAW Women’s Committee to educate people as news develops.

For Frazier, action of the sort is what makes unions so essential. “This is why I like this kind of communal, social-democratic way of collaborating and making images together,” she said. “It really instills what unions are about, which is unity and democracy.”

Such a spirit can be felt in one of the most powerful images in “The Last Cruze,” an aerial view of an action outside the Lordstown union hall in which dozens of UAW members and their families wave signs in a circle as part of the months-long “Drive It Home” campaign, a grassroots effort to convince GM to keep the plant open. Seen today, the picture feels like a premonition of the current strike—as well as a timeless image of workers speaking as one and demanding a better future.

[ad_2]

Source link