[ad_1]

When I got an offer to move halfway across the country to work for the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel in 2000, I had a life that looked a lot like the one I always wanted. I lived in New York and was writing and editing for a successful dot-com. I had an enviable sublet in Midtown and had carved out a new beat covering technology and privacy in the midst of the early online boom.

What made me choose to give it all up and leave for Wisconsin was the intoxicating idea of writing about art. I had written about culture occasionally, but it had never really occurred to me that I could marry my passion for journalism to my love of art. I had studied both in college, but covering culture full-time seemed implausible. Even then, arts-writing jobs were rare.

In Milwaukee, I discovered a precarious but rigorous cultural scene supported by artists who embraced their obscurity. As I’ve come to learn during my nearly two decades in the city, many in Milwaukee enjoy the freedoms that accompany a certain lack of visibility—in a kind of mix of Midwestern pragmatism and artful ambition marked by independence and generosity. I have been nourished by what artists make here and have also come to better understand the intimate relationship between art and place.

I had been a culture writer for the paper for a few years—discovering how art can be a tool for progress and justice, and still finding my voice as a critic—when journalism began its long chase of readers across the internet. Initially, the digital turn seemed full of promise. It gave me the tools to build a loyal community around what I did, to experiment with different forms of criticism and to connect to larger art-world debates.

But then the downsizings began. Across the country in the mid-’00s, newsroom layoffs became routine—and culture sections were often the first and the hardest hit. When art critics started losing their jobs, I had a lot of questions. How many readers would have a chance encounter with an art review while paging through a newspaper, as they had for generations? What would it mean if art criticism were limited to big-city publications on the coasts or to magazines and websites for people already interested in art? What would happen to flourishing but fragile regional scenes without the catalyst of critics on the ground to cover and evaluate them? How would criticism itself change in the vast, churning internet seas?

That was when my journalistic gut kicked in—there was a story here.

In 2010 I started work on a still-in-progress documentary film about art critics, titled Out of the Picture, to investigate a profession that seemed to be disintegrating. I wanted to know the fate of some of the critics I had discovered thanks to the connective force of the web, and I wanted to grapple with what was happening to art and media—and our changing relationships to both.

More recently, while the Arts & Culture Fellow with the Nieman Foundation for Journalism at Harvard University in 2017, I went deeper into this research and conducted a survey of art writers and critics. Drawing in part on questions from a seminal 2002 study conducted by the now-defunct National Arts Journalism Program at Columbia University under the leadership of András Szántó, I set out to learn about the priorities and pressures in the field. The existence of the earlier study offered a rare opportunity for comparison over a period of upheaval.

After more than 300 writers from some 100 cities in 38 states responded to our questionnaire, the findings were published in March 2019 in Nieman Reports; one of the most important takeaways, for me, was finding out which artists we critics consider to be most worthy of our attention. One of our questions invited respondents to name up to three artists they were most interested in championing, and while this resulted in a list of more than 400 artists and not a lot of consensus, it did tend heavily toward artists of color and indigenous artists. The illustrative group near the top of the list included the likes of the Postcommodity collective, Kerry James Marshall, LaToya Ruby Frazier, Kara Walker, Hank Willis Thomas, and Anicka Yi.

By contrast, back in 2002, Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg, quintessential postwar heavyweights—and white men—were the favorite living artists among art critics. (It’s worth noting that the question was asked differently then, when respondents were given a preselected list of artists to choose from.)

In this moment of cultural reckoning, it makes sense to ask whether critics are equipped to engage the work of today’s most relevant artists—formally, culturally, and politically. In the climate of Black Lives Matter, #MeToo, Decolonize This Place, and the protests at Standing Rock—and as art institutions are rethinking whom they hire and how the story of art gets told—the field of art criticism remains mostly white. About 60 percent of respondents to our survey agreed to answer a question about the race/ethnicity that best describes them. Of those, 167 identified as white, four as black, five as Latino, six as Asian, and 20 as other or mixed ethnicity.

In an era when, as the New York Times’s ambitious “1619 Project” put it, we are beginning to face the truth of our national history of racial oppression, the six critics that respondents named as having the most power to shape conversations about culture—Roberta Smith, Jerry Saltz, Holland Cotter, Peter Schjeldahl, Ben Davis, and Christopher Knight—are all white and based in New York or Los Angeles. (The arts writers who took the survey also indicated that figures working outside the art world’s conventional capitals are overlooked—with 86 percent of respondents saying that criticism today focuses too much on New York and L.A. at the expense of deserving art scenes in the rest of the country.)

Courtesy John Simon and Portrait Society Gallery, Milwaukee

At the same time, our study hints at a generational shift—it includes more women, more critics of color, and writers from a wider range of purviews. The critics considered influential in our survey who have less than 25 years in the field don’t fit the mold of their forerunners. Writers like Carolina A. Miranda, Hannah Black, Jillian Steinhauer, Hrag Vartanian, Hito Steyerl, and Maggie Nelson, to name a few, are as likely to write about narconovelas and forms of capitalism as they are the Whitney Biennial or the revamped Museum of Modern Art. They write broadly about culture and society, addressing ideas that happen to surface through contemporary art.

Despite all the downward pressure on the media industry, our digital era has inspired an artistry in criticism itself, with experimentation happening on the fringe and outside of traditional media. There is a vanguard of projects that bear resemblances to memoir, fiction, stand-up comedy, Tumblr manifestos, performance, and binge-worthy TV, among other things. The collective enterprise known as DIS, for example, created a Netflix-esque online channel for heady but approachable shows on art and ideas with explorations of the nature of truth (“from Courbet to the Kardashians”) and critiques of Gretchen Bender’s video work via a faux focus group. Triple Canopy publishes collections of high-concept research projects that resist the internet’s speed by unfurling over months. The thinking behind projects like these tends to be intricate and dense—and the audiences for them dedicated and influential, however limited in size.

Indeed, one of the telling themes that our documentary team has fastened onto while shadowing critics in cities across the country is the soul-crushing nature of the numbers game and the related struggle to capture and hold an audience’s attention. The web favors certain virtues—wit, weirdness, bombast, and urgency—over others. In real time, we’ve witnessed critics watch their well-crafted essays sink to the internet’s depths like a stone. As our cameras rolled, a critic at one of the nation’s largest newspapers darted from one editor’s desk to another, trying to understand why a blog post was bombing and, eventually, with a moving show of emotion, broke down.

Consider too that the once-rare tools of the artist have become ubiquitous, a mere swipe or click away. It is not just that the art world has changed, with Instagrammable art shows and hashtag-driven discourses, but also that art’s place in the world has changed. The population at large is expressing itself and generating visual culture on a scale that is hard to wrap one’s head around. Not everything flowing through our daily lives is art, of course, but some of it is, and the difference between something silly and something serious can be tough to spot. In fact, survey respondents suggested that while their audiences are more informed about art since the rise of the internet, those same audiences are also more confused about it. There is a strong argument to be made that the pathfinding role of critics—the job of discerning what’s genuinely artful and worthy of our collective attention—is more essential than ever.

“My beat is value—deep discussion and dialogue and conflict about what we value,” said Jen Graves, former art critic for the Seattle Stranger, in an interview we filmed for Out of the Picture in 2017. When we spoke, Graves—a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize and the last staff art critic in Seattle at the time—was packing up to leave the position she’d held for more than a decade. “I deliberately worked in markets that were not New York and L.A.,” she added. “I deliberately worked in outlets that were general interest. And I did it—importantly, for me—embedded in a civic context, in a city, where I had to be accountable.”

There are many ways to describe the “value” that Graves identified. I’ve long believed that one of art’s central qualities is that it connects us to the experiences of others across many kinds of differences and divides. It prompts empathy. That quality is indispensable right now on a global scale—and a local one too.

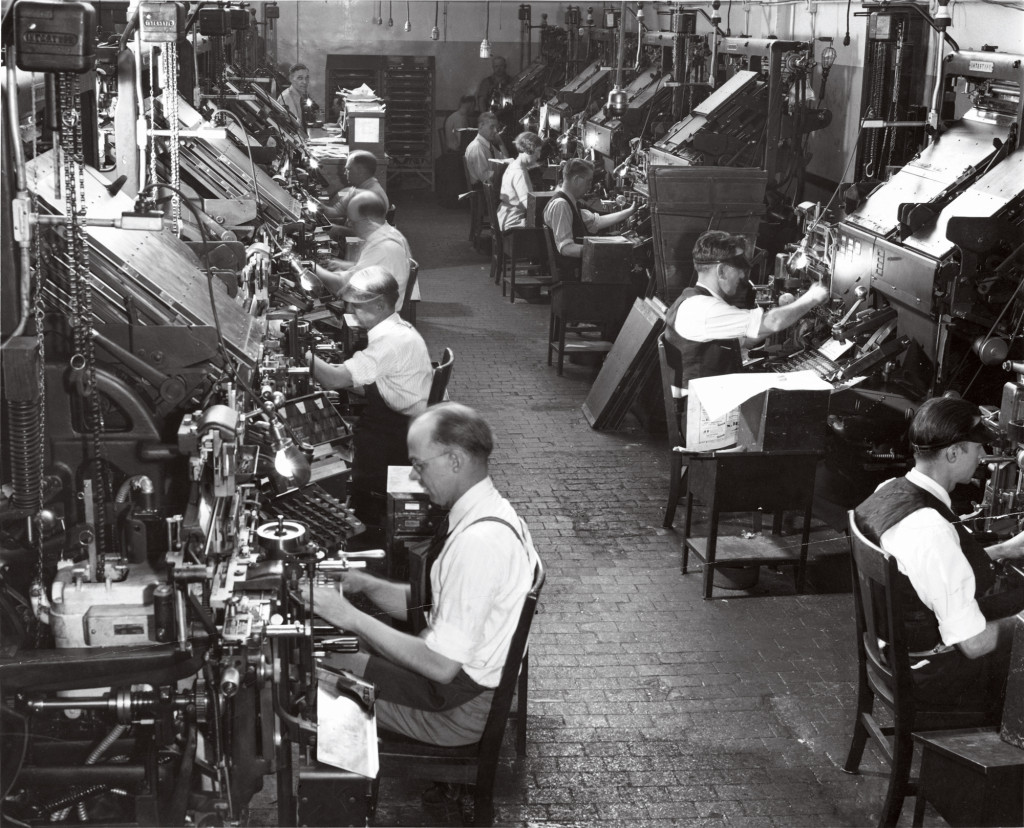

That’s what I’ve learned in Milwaukee. But it’s a lesson I’m pursuing in new ways these days, since I became part of my own story earlier this year. After more than 18 years at the Journal Sentinel, my job as art and architecture critic was eliminated in a system-wide downsizing. When I walked out the door for the final time last February, I left a building that once housed printing presses in the basement and—such was the paper’s commitment to culture—an actual newspaper-run art gallery overseen by the critics who preceded me decades earlier. That’s when I became just another independent writer finding my way and wondering how—in this period of change, expansiveness, and collapse—the role of the critic can continue.

A version of this article appeared in the Winter 2020 issue of ARTnews, under the title “Critical Condition.”

[ad_2]

Source link