[ad_1]

COURTESY THE ARTIST AND CLEARING NEW YORK AND BRUSSELS

Artists from Thailand have long been hard to find beyond the borders of home. Among the few with international reach is Rirkrit Tiravanija, who cooked his way into the heart of the art world by serving meals in galleries. And the late Montien Boonma received acclaim for work that has traveled far and wide. Recently, however, the lack of visibility for Thai artists has started to change, thanks to key showings in biennials and group shows around the world.

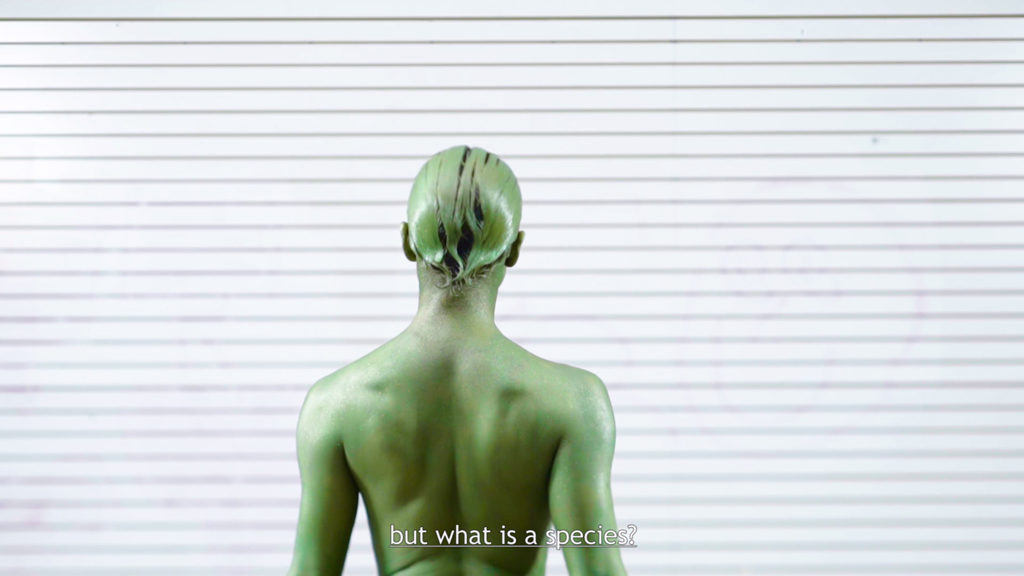

One of today’s busiest artists of Thai descent is Korakrit Arunanondchai. Born in Bangkok in 1986, he is currently based in New York and, in the coming months, will feature in the Venice Biennale and the Whitney Biennial. Other recent milestones include overseeing Ghost: 2561, a triennial for video installations and performance art in Bangkok last fall.

Arunanondchai’s own work tends to combine footage he shoots and images he finds online, and it often weaves together quasi-spiritual musings on the world’s current political state with autobiographical narratives. At the Whitney Biennial, he will show with history in a room filled with people with funny names 4 (2017), which features sequences with his dementia-affected grandmother and documentary-style clips aided by a hypnotic epistolary exchange with a drone spirit voiced in French by his mother. While paying homage to Chris Marker’s essay film Sans Soleil (1983), the video poses questions about the future of the human species and bodies in the digital age.

“I was documenting the moment Trump became president, the Women’s March, and the last king of Thailand [who] passed away,” Arunanondchai said in his studio in New York’s Chinatown. “I pulled everything together into a narrative that is a metaphor for our species and the relationships we build.”

©STAN NARTEN/COURTESY THE ARTIST AND CLEARING NEW YORK AND BRUSSELS

Arunanondchai has been living in America for 14 years and studied at the Rhode Island School of Design and Columbia University. But any designation of him as an American artist or a Thai artist does not quite fit. “This is a binary I am trying to break,” he said, adding that he identifies as part of “a larger creative network centered around the art world.”

Jane Panetta, who is curating this year’s Whitney Biennial with Rujeko Hockley, said that broken binaries can be a benefit. “We have been thinking about how we can expand the definition of an American artist to include artists navigating between cultures, and Krit really fits into that interest perfectly,” she said. “Even though he has been here for quite a while and spends the majority of his time here, he is going back to Thailand regularly, thinking about what is happening there culturally, using that material in the work, and splicing that with footage of the American landscape and American political questions.” Panetta said he generates a “third space”—between Thailand, America, and beyond.

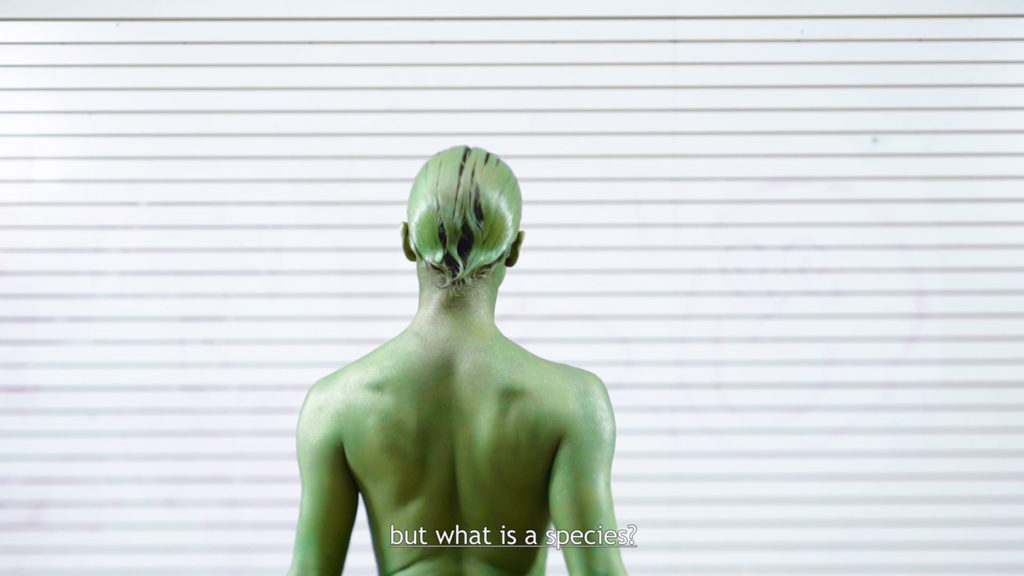

Another artist working within that “third space” is filmmaker Apichatpong Weerasethakul, who recently won the prestigious Artes Mundi prize, which carries with it a grant of £40,000 (about $52,200). For a show related to the award at National Museum Cardiff, Weerasethakul exhibited his film Invisibility (2016), which addresses the malaise caused by Thailand’s political corruption in the past and present.

Weerasethakul is based in Thailand, in the city of Chiang Mai. But his international star has risen with marks of distinction such as winning the Palme d’Or at the 2010 Cannes Film Festival for Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives. His work has also been widely seen in the art world, with showings at such venues as the Oklahoma City Museum of Art; the Contemporary Art Center in Vilnius, Lithuania; the Museum of Contemporary Art and Design in Manila, the Philippines; the School of the Art Institute of Chicago; and Para Site in Hong Kong.

Weerasethakul’s international exposure allows him to tackle topics that might otherwise not be permissible in the Thai film industry. “He has to veil the content of the work because of the political conditions in Thailand,” said curator Laura Raicovich, who served as one of the jurors of this year’s Artes Mundi prize. Raicovich noted the ways he addresses “questions of sexuality and living a public life in relation to different modes of oppression and freedom of speech. I find that thread is very compelling.”

POLLY THOMAS/COURTESY THE ARTIST AND ANTHONY REYNOLDS GALLERY, LONDON

In recent years, the Bangkok Biennial, the Bangkok Art Biennale, and the Thailand Biennial have drawn eyes to Thailand, but artists and others there face dark realities. “Thailand has seen a great deal of sociopolitical turmoil over the past 15 years or so, and this has definitely had an effect on the arts in terms of artistic practice, the market, and infrastructure,” said Tyler Rollins, a New York gallerist who represents the mid-career Thai artists Araya Rasdjarmrearnsook, Pinaree Sanpitak, and Manit Sriwanichpoom.

The country’s current economic slump and the military coup of 2014, complicated by the death of the former monarch and the appointment of a less-respected king, are integral to much of the work being made by Thai artists today. Given the intensity of censorship, artists are often forced to resort to symbolism and other conceptual strategies to provoke debate without making explicit statements about the country’s political situation.

Gridthiya Gaweewong, artistic director of the Jim Thompson Art Center in Bangkok, spoke of the difficulties there. “For many artists of the younger generation who want to criticize socio-political issues, it’s unavoidable to speak about the king as the highest peak of the pyramid, the invisible hands that control us,” she said. “We have to use symbols, and it can be very difficult for people outside Thailand to understand them.”

In spite—or maybe because—of its coded nature, art has thrived. “Every time there is a political collapse, the art is very vibrant,” Gaweewong said. “We don’t really have an outlet to express ourselves—that is why, in the worst political difficulties, we have three biennales.”

COURTESY THE ARTIST AND TYLER ROLLINS FINE ART

Manit Sriwanichpoom, who was born in 1961 and lived through the democracy student movements of the ’70s, said the current situation is very different from what he faced early in his career. “The political situation is quite complex in comparison to my generation, for which it was very clear that the army was against the people,” he said. Sriwanichpoom’s photographs of Thailand’s burgeoning malls and historical sites frequently feature a recurring character, Pink Man—a lone figure wielding a shopping cart as a commentary on how consumerism has supplanted activism in the current political climate.

Dusadee Huntrakul, a Bangkok-based artist decades younger than Sriwanichpoom, said the hardest part of being a Thai artist is “living [under] an unstable governing structure that lacks a vision. It is a situation where bad decisions and wrong doings get blurred.” For his show last year at 100 Tonson Gallery in Bangkok, Huntrakul displayed a series of ceramics alongside hyper-realistic drawings of snakes in toilets—a reference to the city’s poor infrastructure, which allows nature to penetrate the urban landscape.

Miti Ruangkritya, trained as a documentary photographer, creates pointed installations addressing issues ranging from Bangkok’s real estate boom and pollution to political advertisements and protests. “If we are going to touch on political issues, we have to be quite careful,” he said of work for which he has chosen to concentrate on the environment and human rights rather than direct confrontations with the military regime.

For many of these artists, other problems include the lack of an art-world infrastructure in Thailand. While Bangkok has exciting galleries including 100 Tonson, Bangkok CityCity, and Ver Gallery (founded by Rirkrit Tiravanija), collectors are scant, and so are museums for contemporary art (with the notable exception of MAIIAM Contemporary Art Museum in Chiang Mai).

But artists often stage their own exhibitions in addition to producing work. Sriwanichpoom, for example, runs Kathmandu Gallery, which specializes in photography, and Huntrakul recently curated a group show, “New/Old Savages,” at Bangkok University Gallery. Along with Ghost: 2561, the latest Bangkok Biennial was an artist-driven project, allowing anyone who wanted to participate to have a pavilion. Some 200 artists took part.

POL DUSSAUSSOIS MARTINEZ/COURTESY THE ARTIST

Lee Anantawat, one of the key organizers of the Bangkok Biennial, opened the alternative space Speedy Grandma in 2012. “I want to feel comfortable when I go to see exhibitions, so I wanted to create that kind of a space in Bangkok,” she said. “I felt it would be good to have some place for young emerging artists that maybe have no other place to exhibit their work.”

Alternative spaces such as Speedy Grandma have had a profound impact on Thai artists’ careers. Orawan Arunrak showed her work for the first time there in 2013, and she will have her first solo show at Bangkok CityCity gallery this year, exhibiting a continuation of her project EXIT-ENTRANCE, which involves interviews with monks and other people at a Thai temple in Berlin.

According to Gaweewong, the Thompson Art Center director, alternative spaces can abound because Thailand is not facing the pressures of an art market more developed elsewhere in Southeast Asia. “The market has never been the problem for us, because we don’t have a market,” she said. “What we have is artists who are making interesting work but don’t have the support from either the government or private foundations or the market.”

Nonetheless, Thai artists have been developing a strong presence both at home and abroad. “Maybe if we had a strong market like Indonesia and government support like Singapore, [artists and curators] would not have gone out of Thailand and had an impact,” Gaweewong said. “Maybe we have succeeded internationally because outside is our only option.”

[ad_2]

Source link