[ad_1]

Aida Muluneh, The Departure, 2016.

COURTESY THE ARTIST AND DAVID KRUT PROJECTS

Behind a corrugated metal gate on an otherwise nondescript swath of land in the Old Airport neighborhood of Addis Ababa is an extraordinary sight: a utopian project taking the form of earthen buildings and gardens nurtured in the name of art. During a visit a few months ago, teams of masons darted here and there, working feverishly in advance of the opening of a new institution for Ethiopia with roots growing back decades. Gardeners in sunhats tended beds of herbs planted in the soil. Bright-colored birds, a rare sight elsewhere in the city, hopped along the steps of an amphitheater hewn from a hill.

This is the site of the Zoma Museum, a new eco-homage to Ethiopia’s indigenous architecture as well as a distinctly African home for contemporary art. A new incarnation of what had previously been known as the Zoma Contemporary Art Center, the Zoma Museum, opening in June, is the creation of curator and cultural anthropologist Meskerem Assegued and artist Elias Sime, who have been working on it in various ways for 20 years, steadily buying up land plot by plot. “If you want to do something good, it takes time,” Assegued told me. “People think we’re rich. But we’re just rich with people—a lot of good people.”

The grounds themselves are a compelling work of Land Art. Looking out across the sloping hills, sightlines deceive and lend perspectival intimacy that toys with a sense of distance. At a glance, it seems that no part of the compound is hidden from view, curving bowl-like and descending to the Akaki River. A central cluster of mud structures, which Sime and his skilled masons have been building over time, will accommodate exhibition space for artists from Africa and around the world, as well as a library, bakery, and café. The museum will also operate a school for vernacular architecture while maintaining a kindergarten that had been started on the property before Zoma became involved.

The inspiration for all this was a road trip around Ethiopia. As we toured the new Zoma grounds, Assegued described a pivotal journey in the mid-1990s when she was in her twenties. Home on break from studying clinical psychology at a small university in Missouri, she drove north through the Ethiopian towns of Gonder, Wollo, and Yeha. At one point, a stone house caught her eye and captivated her for how it held together, without the use of mortar or cement, by way of an intricate stone-cutting technique. Along the way, she stopped at numerous structures, asking local builders about their methods and documenting her research with photographs. “There were all these techniques all over the country, just hidden,” Assegued said. “There was an incredible amount of knowledge. This country is rich with that.”

After graduating, she dropped psychology in favor of graduate work in cultural anthropology and spent more time doing fieldwork in Africa. “I was angry that it was being wasted,” she said of the homegrown creativity she’d discovered in the architecture she saw. “It was looked at as backward, but what I saw was very futuristic—in every building, I could see the future.”

The future she envisioned for such ancient ingenuity—and has worked since to continue with Zoma—required infrastructure for independence. In addition to building exhibition space and offsite studios for creating artwork, the Zoma Museum developed a unique water system to avoid reliance on Addis Ababa’s pipes, allowing gardeners there to grow fresh produce. At the same time, a small family of cows will remain onsite in a newly built stable, their dairy production supervised by a previous landowner: a woman Assegued refers to as Emama, a term of respect and endearment. “I’d rather learn from her than someone I don’t know,” Assegued said. “She loves the cows.”

The grounds at ZOMA Museum in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

MESKEREM ASSEGUED

To many development experts, Ethiopia is exemplary of what they see as Africa’s steady march into the future. The country has a burgeoning entrepreneurial middle class, and a historic new rail line to the neighboring coastal nation Djibouti has given direct access to nearby ports. Near the Sudanese border, Italian engineers are helping construct the largest hydroelectric dam in Africa while, in Addis Ababa, Chinese developers are helping build an 80,000-seat mega-stadium. In April of 2018, a promising young prime minister, Abiy Ahmed, was appointed.

But the path to progress is formidable still. Violent government crackdowns of peaceful protests have reawakened fears of a new era of totalitarianism, led this time not by a communist dictatorship but authoritarian global capital, as unrest brews among a disgruntled young generation that feels left out of development dreams. Only an hour outside Addis Ababa, the charred remains of a pickup truck on the roadside, evidence of a recent clash between authorities and protesters, indicated there is clearly much work to be done to square the country’s globalist visions of the future with the pressing realities of economic inequality and exploitation. In certain ways, a bold flourishing of Ethiopian art is at the forefront of that work.

“All people want to do is work, earn a living, educate their children,” said artist Aida Muluneh, sitting behind a desk at her creative consulting office in Addis Ababa. “We need leadership that will take us to the next frontier. We’re really at the crossroads.”

Earlier that day, Muluneh walked with me down one of the city’s bustling avenues. I was in town from New York, and it had been a decade since my last visit to Addis Ababa, where my parents were born. Taxis and trucks swerved through intersections, clouding the air with exhaust. Young waiters in black T-shirts flitted between the tables of a new pizza place packed with locals and expatriates. Donkeys crossed the street carrying cinder blocks to construction sites. Muluneh observed, “We’re a working people. It’s not comfortable work. We’re not that generation to be comfortable yet, but the point of putting the work in now is for the next generation to take it to the next step.”

A few weeks prior to our meeting, Muluneh had texted me a few photographs from “The Memory of Hope,” a series that features her trademarks: flat, shadowless primary colors, African women in striking face paint staring defiantly at the viewer, frames filled with sly coded references to black diaspora motifs and her own personal experience.

One of them featured two identical East African women in ghostly white face paint—one seated, the other standing. Between them was a sinister shadow and a stream of liquid pouring impossibly between the small spouts of one blue jebena, a type of Ethiopian coffeepot, into another. A second photo had the same white-faced model holding a half-moon of watermelon as a blue noose dangles beside her—an image Muluneh said was inspired by U.S. President Donald Trump’s sympathetic remarks about white supremacists in Charlottesville, Virginia. Over text, I asked her where she found inspiration and she wrote back, “From watching the news.”

Aida Muluneh, All in One, 2016.

COURTESY THE ARTIST AND DAVID KRUT PROJECTS

It was Muluneh’s ability to “construct a character” in her pictures that led curator Lucy Gallun to include eight of her photographs in the recent survey “Being: New Photography 2018” at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Gallun chose All in One (2016)—a white-faced model with four hands, one of them waving hello—for the first work in the show. “In an exhibition about multiple representations of personhood and approaches to identity through photography,” Gallun said, “I wanted to open the show with a figurative image that immediately announces itself as layered.”

Through such characters, Muluneh’s work explores the layered psychic realms of blackness and womanhood that the African-American science fiction writer Octavia Butler, whom she cites as a major influence, explored through her otherworldly prose. In the process, Muluneh’s work has helped reorient the way black women are perceived. “As women, especially as African women,” Muluneh said, “we forget—and the world forgets—our positioning in history and religion and culture.”

The Departure (2016), also included in the MoMA show, is a layer cake of collective memory. Shot in the grand but defunct main train station in Addis, it is one of Muluneh’s most personal works, evoking her family’s escape from Ethiopia during the Red Terror, a period of brutal dictatorship in the 1970s and ’80s that resulted in torture and murder as well as the exile of large swaths of an entire young, educated generation that includes Muluneh’s parents and mine. “We left this country not by choice. For my mother there was really no other way,” said Muluneh, who, after growing up outside the country, returned to the place of her birth a decade ago and has remained ever since.

Exploring new modes of representing the historical image of the black woman has also been a focus of Muluneh’s work as an arts organizer, educator, and entrepreneur. She often repeats a Ghanaian proverb: “When you teach a boy, you teach an individual. When you teach a girl, you teach a nation.” In her own case, Muluneh envisions not just a new nation but a global lens newly focused on Africa.

In 2010 Muluneh founded a creative consulting firm and arts organization, Desta for Africa, with the goal of promoting development through art. One of the group’s projects is Addis Foto Fest, an international biennial for fine art, photojournalism, and fashion photography. In 2016 the festival hosted more than 100 exhibitors from 31 countries; the fifth edition is scheduled this year in December. Muluneh also organizes free workshops for young photographers and, though her fine art work has gained international acclaim, she plans to use more mainstream mediums in the future to help spread her message: fashion photography, feature filmmaking, and experimenting with embedding elements of her art into commercial merchandise. “I’m not really a believer in art becoming the exercise of the elite,” she said. “I do believe in the masses.”

For Muluneh, art and arts education are not academic exercises to be confined to galleries and classrooms, which can be forbiddingly exclusive spaces. “Regardless of circumstances, our innovations and creativity manage to shine through,” she said of herself and her fellow Ethiopians. “It’s not based on the level of education or how much money you got or what kind of space you’re in—if you’re in a city that understands your work or not. It’s just the need to express, which to me is very African.”

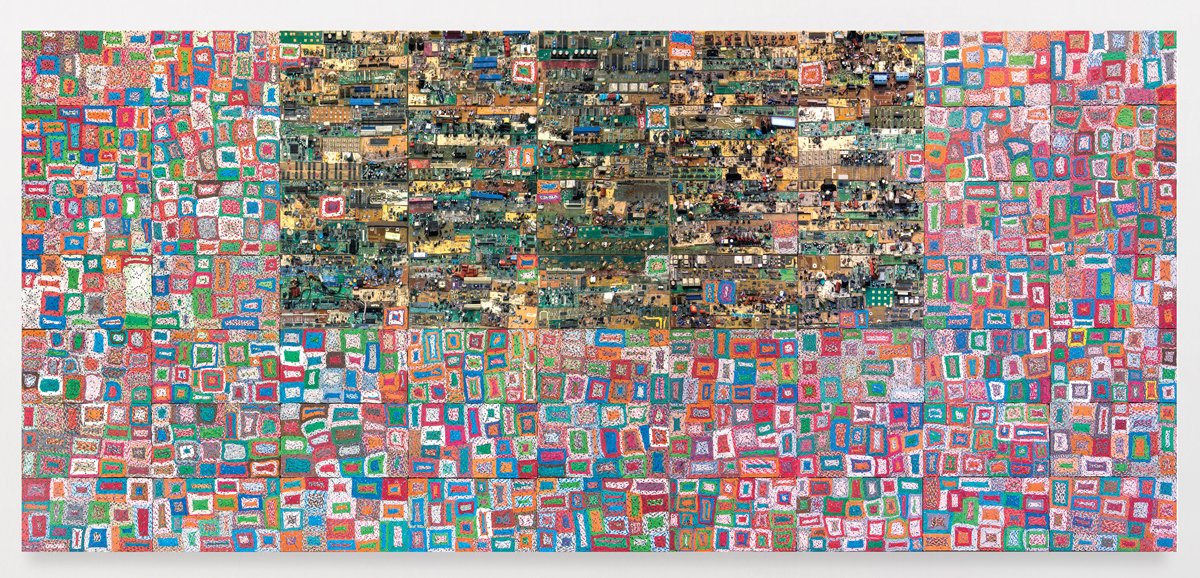

Elias Sime, Tightrope: In Boxes, 2017.

COURTESY JAMES COHAN GALLERY

In the collective context of Zoma, Assegued and Sime are a study in contrasts—Assegued effusive and fast-talking, a globetrotter who favors chunky jewelry and chic black clothes, and Sime shy and intense, while speaking in careful snippets of Amharic, seeming more at home in his work than in the world. Assegued is Zoma’s anthropologist, environmentalist, botanist, and publicity director; Sime its architect, furniture maker, sculptor, collagist, foreman, and teacher.

Sime, 49, has lived in Addis Ababa his whole life and travels outside the country only on rare occasions. “There was nothing that I wasn’t exposed to growing up,” he told me. “When you learn art in Ethiopia, you learn everything, all together.”

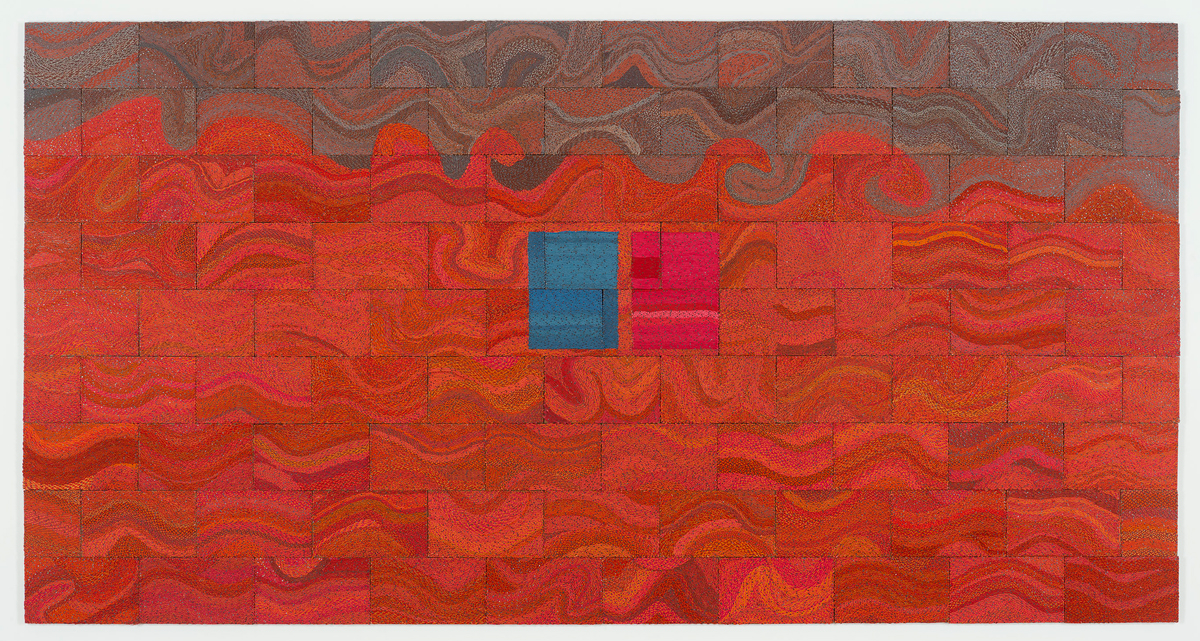

He started his art career in a working-class neighborhood in Addis Ababa, selling his social-realist collages of beggars at small hotel exhibitions. “I wanted to show the state of Addis Ababa, kids selling peanuts, things I grew up seeing,” he said. But by the time Assegued discovered his work, in 2001, he’d moved on to abstract collages made from buttons, bottle caps, things the local merchants discarded. (His breakthrough, Assegued would later learn, came about in the wake of a break-up with his girlfriend that drove him to hole up in his studio. “I didn’t leave my house for many years,” Sime told me.) “I transform things I find into art,” Sime said. “I prefer things that have touched or been in contact with people.”

In one of her early artistic activities in Addis Ababa, Assegued organized an arts collective called ArtSpace, which was largely inspired by the stone and earthwork traditions she observed on her fieldwork trips. In 2002 the Museum of Modern Art invited her to take part in its African Museum Professionals Workshop, where, along with 14 other curators and educators from sub-Saharan Africa, she studied institutional practices in New York, Los Angeles, and Washington, D.C.

In Ethiopia, Assegued had been aware of an environment of fear in the art scene, a holdover of the Red Terror years when free expression and public assembly were violently suppressed. When she returned once again to Addis Ababa after the MoMA program, she resolved to shake things up, and her first project was Giziawi #1, a landmark three-day art happening with exhibitions and performances across the city. There were artworks from 45 local and international artists, an enormous tent in the middle of the centrally located Meskel Square, and a performance by the Ethiopian jazz legend Mulatu Astatke. True to its name—giziawi means “temporary” in Amharic—Assegued burned the massive tent down on the last day. “It was a huge operation. I was just young and crazy,” she said. “But it ended up being extremely successful.”

One of the artists she included in Giziawi #1 was Sime, whose found-object collages, she said, “stunned everyone. I could not believe that there was an artist like this.” After the festival, the two began collaborating on the Zoma Contemporary Art Center, a new initiative to present art by locals and artists from around the world. The first year of programming included the reclusive American artist David Hammons, whom Assegued had met during her workshop at MoMA. On his first trip to Africa, Hammons installed Divine Light at Zoma, a piece he’d created in New York the previous year: an interactive installation for which visitors were given flashlights to explore cavernous, pitch-black rooms. Other early Zoma undertakings included the group show “Addis Ababa Zare” (Addis Ababa Today) in 2005 and multiple exhibitions by Sime, whose work was steadily growing in scale.

A few years ago, American theater director and MacArthur fellow Peter Sellars, who collaborated with Sime on set designs for his January 2010 production of Oedipus Rex in Sydney, Australia, introduced Sime’s work to James Cohan, the New York gallerist who would go on to represent him. “I stopped dead in my tracks when I saw his work,” Cohan said. “There’s something extremely beautiful about the obsessive labor involved, and the narrative behind the work is equally rewarding.”

Over the past three years, Cohan has sold Sime’s work to museums around the world, including the Israel Museum in Jerusalem and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, and Sime has routed a large portion of the money from such sales straight into the Zoma Museum. “If you go into the global market and are able to break into that world, that is very good,” the artist said. “But when you come back, the goal is not to spend your money on big cars and such. You need to have a purpose.”

“We don’t get anything out of this,” Assegued said. “This doesn’t belong to our children. It’s for future generations. It’s a labor of love.”

Later this year, Sime will complete his most ambitious artwork to date, a large piece comprising discarded motherboards and braided electrical wiring to be installed at Facebook’s new Frank Gehry–designed headquarters in Silicon Valley. For her part, Assegued is curating a pavilion for the 2020 Venice Architecture Biennale titled Futuristic Past: Ethiopian Vernacular Architecture, to include interactive virtual reality displays and musical performance by Astatke.

The Zoma Museum is a blend of their visions: like a Sime collage, it is reenvisioning what an art institution can be by way of discarded or neglected objects, traditions, and techniques. Mud structures of Sime’s design play home to different Zoma projects while communing with the time-tested building methods that Assegued discovered on her tour of Ethiopia all those years ago. “They’re all over the world, and they’re being dismissed all over the world,” Assegued said of such designs. When I asked Cohan about the possibility of a mud structure one day appearing in New York, he said, “I’m working my head off trying. It needs to happen. I’ve had one misfire so far, but I’m not giving up.”

With urban development taking place all around it, much of it wasteful, the Zoma Museum offers a kind of rebuttal. Assegued bemoaned the sort of short-sighted push to build up Addis Ababa and other cities like it, suggesting that artists are better off building communities. “To be the greatest artist,” she said, “you should stay away from competition. Coexisting is a survival tool.”

Elias Sime, Tightrope: Against the Wave, 2017.

COURTESY JAMES COHAN GALLERY

The vision and visibility of artists like Sime and Muluneh have inspired others who share connections to Ethiopia. Ezra Wube, an Addis Ababa–born artist now based in Brooklyn, credits a chance encounter with Muluneh in New York for inspiring the Addis Video Art Festival, which he founded in 2015. “I was showing a video in some bar in New York and she was like, ‘You should show this at Meskel Square,’ ” Wube recalled. “I’d never thought about showing my work in a public space.”

The festival, which will present its third edition in 2019, takes a playful, disruptive approach to arts programming with guerilla-style public screenings on busy side streets, rooftops, cafés, and squares. This isn’t without its challenges. At previous screenings, people have idled to watch, curious but questioning—including the police, who shut down one of the festival’s first outdoor screenings. “They didn’t understand,” Wube said. “It’s not a commercial, it’s not a movie—what is it? They thought it was political, so they were nervous. We were like, ‘It’s just free art.’ ”

Salome Asega, a New York–based artist of Ethiopian descent and a current technology fellow at the Ford Foundation, said the work of Muluneh and Sime suggested to her the beginnings of a new tradition that she as an American-born artist could incorporate and build on. Sparked by a trip to Addis Ababa in 2012, while studying interactive design at Parsons School of Design, Asega discovered a bag of photographs under her mother’s bed. In the process of scanning and uploading the images to share with family, she began manipulating them with simple computer programs and printing them as postcards.

“I started communicating with my grandmother that way, because I thought it was a way to build a bridge between past and present and future,” Asega said. Later that same year, it became her postcard mailing project on the line, exhibited at NURTUREart in Brooklyn earlier this year. “Part of what I love about this project,” she said, “is that the postcard has been physically touched by so many people in the process of traveling.”

A version of this story originally appeared in the Summer 2018 issue of ARTnews on page 70 under the title “Ethiopian Enterprise.”

[ad_2]

Source link