[ad_1]

The Seven on Seven logo on the facade of the New Museum.

ALEX GREENBERGER/ARTNEWS

Confused New Yorkers stood in front of the New Museum over the weekend wondering about a giant oval-shaped sticker covering most of the ground floor with a cryptic message: 7 x 7. They would’ve been forgiven for thinking it was an artwork—Zachary Kaplan, the executive director of Rhizome, the art-and-technology-focused organization responsible for the oddity, said it looked like a giant skateboard decal. But as it happened, the communiqué was advertising the 10th annual Seven on Seven conference, which pairs seven artists and seven technologists with a simple (and vague) directive for each of the duos to make something for the occasion.

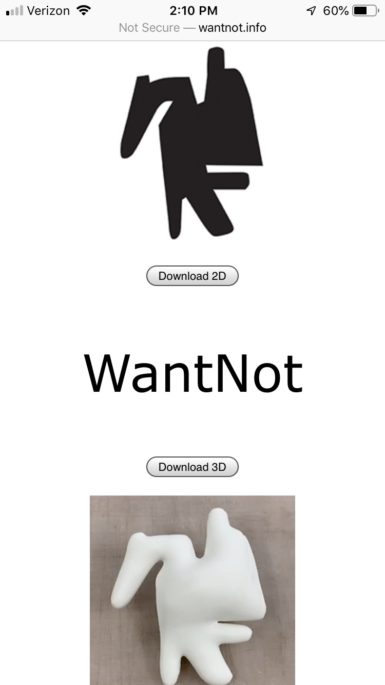

“Fate brought us together,” Laura Welcher, the director of operations at the Long Now Foundation, said admiringly of her partner that day, the artist Hayal Pozanti. United by a shared interest in linguistics, the two self-classified “language nerds” presented a new work—WantNot, a glyph of sorts intended to communicate mutual respect to future humans (or aliens) who might come upon it. They 3D-printed their curious object, which resembles an abstract bird with its head bent, using terracotta, a biodegradable substance. And they shared the news that anyone who wanted to could do the same, thanks to a website they built. “We encourage the idea of not getting too attached to wanting WantNot,” Pozanti said.

An interest in the future of language continued in a presentation by artist Qiu Zhijie and AI researcher He Xiaodong, who created a program that could map connections between uttered words. Much of Qiu’s work has focused on cartography in the context of colonialism, globalism, and capitalism, and the piece here—a version of which is now on view at the artist’s retrospective at Beijing’s Ullens Center for Contemporary Art—brought his concerns into the digital age. As Qiu read a famed soliloquy from Hamlet, the machine at first didn’t respond. “What happened?” the artist wondered, gazing up at the screen. Suddenly, words shot out from “be” and “question,” and all kinds of links were fused. “Actually,” Qiu said, “it performs much better in Chinese.”

Hayal Pozanti and Laura Welcher’s WantNot website.

Artist Sarah Meyohas and Tarun Chitra, the founder of the blockchain platform Gauntlet Networks, screened a version of an augmented-reality project in which yellow birds flew around a screen. What might have seemed like a riff on cheery winged creatures had a dark undercurrent, however, as the birds represented the performance of NASDAQ stocks on the market. Dispersals marked economic downturns, and upward flights correlated to economic success. Meyohas and Chitra also showed similar work engaging airplane delays, New York subway usage, and cryptocurrency activity, challenging attendees to guess which was which. “We are just the patterns we see in nature,” Chitra said.

If the day’s first half tended toward seriousness, the second half was all irreverence. Artist Matthew Angelo Harrison, to be featured in the upcoming Whitney Biennial, and DJ Trevor McFedries produced one of the conference’s most memorable projects in the form of a video with a computer-generated character that spouted different people’s recollections of matches on dating apps. The voices from interviews conducted at Detroit coffee shops spoke of nice Jewish boys and aggressive goth girls, and they were set against footage filmed at Dia:Beacon. Since people often fixate on art by white men at that upstate museum—“the hunks of Dia:Beacon,” Harrison said of artists like Richard Serra, Donald Judd, and Robert Smithson—the project creators drew a connection between that and behavior on Tinder, Bumble, and Grindr. “When given cultural choices, people are reverting to memes,” McFedries said.

American Artist and Rashida Richardson, the director of policy research at the machine-learning organization AI Now, showed informercials for Ally AI, a fake product that would advise users on how to comport themselves when faced with situations involving racism. Their commercials were slick, with white office settings and screens within screens. In one, a white woman steps up from her computer and beholds a black coworker’s hair; she pauses for a second, gripped with the feeling that she probably shouldn’t touch it, and then asks Ally AI whether it’s acceptable to do so. “It’s not,” the product responded in a Siri-esque voice.

The question of how machines might teach us to behave was also at the center of a project by developer/activist James La Marre and artist Artie Vierkant—who last year wrote an op-ed for ARTnews about the art world and health care—that highlighted pharmaceutical companies’ stranglehold on patents for drugs. With the blessing of Constant Dullaart, who for a project of his own had thousands of bots follow the accounts of his art-world colleagues, the pair enlisted fake Twitter users to spam the social media accounts of drug companies like Purdue Pharmaceuticals and Mylan with garbled messages about their misdoings. “This personify fake on many levels #NationalDrugTakeBackDay today,” one such bot tweeted at Mylan.

vitamin A board members

— Thomas Jacobs (@Dagueraunt) April 27, 2019

In one of the day’s most intriguing collaborations, artist Rachel Rose said of her partner Kirstin Hagelskjaer Petersen (a professor of engineering at Cornell University), “We discovered that we were pregnant and due the same week. Magic is all around us.” The duo’s Seven on Seven project grew out of Rose’s ongoing inquiry into agrarian culture in 17th-century England and a mutual interest in robotics. After Rose had come across early designs for robot insects, she and Petersen decided to create creatures of the sort to build environmentally sustainable structures for the future. After showing versions of their insects in action, Rose said their collaboration would continue on “in real life, not Rhizome life.”

“Anyone can be a roboticist today,” Petersen told Rose, in an attempt to instill some of her engineer’s confidence in an artist. Rose laughed and said, “Uh, definitely not.”

[ad_2]

Source link