[ad_1]

Lotty Rosenfeld, who through the simple act of creating a line on a street in Chile mounted an important artistic and political intervention against an oppressive government, has died at the age of 77. The cause of death was lung cancer, according to the Chilean newspaper La Tercera, which first reported the news.

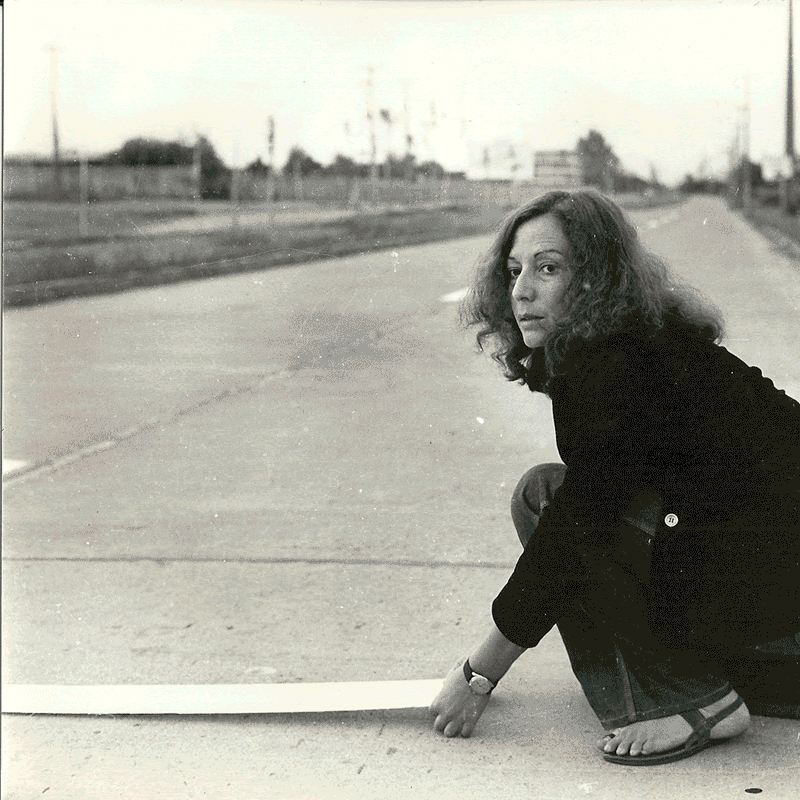

Rosenfeld might best be remembered for her 1979 performance work, Una milla de cruces sobre el pavimento (A mile of crosses on the pavement). In a video documenting the performance, Rosenfeld is seen kneeling along Santiago’s Avenida Manquehue as she measures a piece of cloth against the street’s dotted dividing lines. She then turns her fabric to be perpendicular with the lines and adheres them to the street, creating crosses. Rosenfeld repeats the action over and over again until Avenida Manquehue’s traffic lines are rendered illegible—a system of control made useless.

The piece was a response to the 1973 military coup in Chile that deposed of the democratically elected president Salvador Allende, who was soon replaced by dictator Augusto Pinochet. The simple action was then an attempt “to reclaim public spaces that had been seized under the regime,” according to Rosenfeld’s artist entry for the Hammer Museum’s acclaimed 2017 traveling exhibition “Radical Women: Latin American Art, 1960–1985,” which included the piece. “She thus turned the traffic markers into crosses or plus signs. Through this and other works Rosenfeld attempted to intervene in the public reception of signs and social realities, transgressing the mandates inherent in the social order.”

In an interview last year with La Tercera, Rosenfeld said, “I was looking for a sign in the public space that would allow me to work with unconscious obedience against the established order, to intervene in the sign allowed me to highlight one of the daily ways in which power operates. What is least seen is what is most present.”

Courtesy 1 Mira Madrid

An edition of Una milla was acquired by the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 2018 and was included in the museum’s rehang of its permanent collection galleries when it reopened after a renovation last fall. Installed on the fourth floor in a room titled “War Within, War Without,” Rosenfeld’s work was positioned among works by other artists including Philip Guston, Benny Andrews, Marisol, Barbara Jones-Hogu, Ibrahim El-Salahi, Nancy Spero, and others.

Rosenfeld has also similarly re-created Una milla in various locations around the world, particularly those associated with political power such as the Allied Checkpoint in Berlin, the Arc de Triomphe in Paris, and the White House in Washington, D.C. It was also presented during Documenta 12, where it was accidentally removed by sanitation workers in Kassel, Germany, where the exhibition takes place. (It is unclear if Rosenfeld’s intervention was an official commission by the Documenta curatorial team.) Of the removal, Rosenfeld said at the time, according to the English-language German publication DW News, “It’s an act of violence and I feel I’ve been completely disregarded. They scraped it off with shovels and just threw it into the trash. That hurt.”

In an email announcing the artist’s death, Rosenfeld’s gallery 1 Mira Madrid called her one of the gallery’s “most emblematic artists.” It added, “You will always be with us. The line was her weapon.”

Courtesy 1 Mira Madrid

Born Carlota Eugenia Rosenfeld Villarreal in Santiago, Chile, in 1943, Lotty Rosenfeld studied at the Escuela de Artes Aplicadas, Universidad de Chile, in Santiago, and originally made a name for herself as a printmaker. In 1979, she co-founded the collective CADA (Colectivo de Acciones de Arte) with the artists Diamela Eltit and Juan Castillo as well as poet Raúl Zurita and sociologist Fernando Balcells. (In addition to Una milla, MoMA also owns three videos made by CADA between 1979 and 1981.)

With the collective, Rosenfeld created a series of public performances that also responded to Chile’s dictatorship. Though often brief, these works typically involved months of planning. For 1979’s Inversión de Escena, the group parked eight trucks in front of Chile’s Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes, in an attempt to shut the museum down. The trucks were provided by the company Soprole after CADA convinced its marketing manager that the action would give the business free advertising.

Though her work was still somewhat underknown in the United States, Rosenfeld was a celebrated artist in Chile, where Una milla had become an iconic work. In 2007, Rosenfeld was named Visual Artist of the Year by Chile’s National Council of the Arts, and she was one of two artists (the other being Paz Errázuriz) who represented Chile at the Venice Biennale in 2015.

Despite the acclaim and recent acquisitions of her work, Rosenfeld said in her recent interview with La Tercera that her art was itself a protest against this recognition—and always had been. “I feel [that my work] is part of a long tradition of [the questioning of art practices], but by no way [belongs] to a canon. That some museums have acquired my works does not change the fact that my work resists all normalization. My work continues to be a warning against authoritarianism and exploitation.”

[ad_2]

Source link