[ad_1]

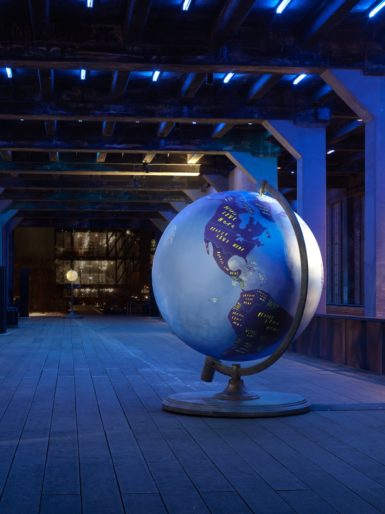

Installation view of “Oliver Jeffers: For All We Know,” 2019, at Bryce Wolkowitz Gallery, New York.

COURTESY THE ARTIST AND BRYCE WOLKOWITZ GALLERY

“If you are in a shipwreck and all the boats are gone,” R. Buckminster Fuller wrote in 1968, “a piano top buoyant enough to keep you afloat that comes along makes a fortuitous life preserver. But this is not to say that the best way to design a life preserver is in the form of a piano top.” However effective it might be for saving a life, a piano top can make for an intriguing subject for art—as one does in Oliver Jeffers’s exhibition at Bryce Wolkowitz Gallery in New York, where images of piano tops appear in paintings and sculpture as part a hanging installation that also includes a globe, a matchstick, a rowboat, and a car.

“This was fun,” Jeffers said, citing the Fuller quote as an inspiration for his arrangement in the space. “My work is too playful to just have canvases on walls.” Indeed, Jeffers’s practice extends beyond painting and installation. The Brooklyn-based artist is also an author and illustrator of children’s books, and his current exhibition, “For All We Know,” shares similarities with his 2017 bestseller Here We Are: Notes for Surviving the Planet, a how-to guide for navigating Earth and co-existing with its many creatures.

Though he is distinguished for his books (which have won him a New York Times Best Illustrated Children’s Book Award and an Irish Book Award, among other prizes), Jeffers began his career as a painter and discovered bookmaking “by accident.” “The books have always come from the things that I’m exploring in my fine art practice, and there’s a humor and accessibility to the fine art that wouldn’t exist without the books,” he said. Unlike books, however, art has no clear beginning, middle, or end. “This is so much more freewheeling and nebulous than that,” he said of his exhibition.

Oliver Jeffers, Constellation Road Map, 2018, oil on canvas.

COURTESY THE ARTIST AND BRYCE WOLKOWITZ GALLERY

The show features richly colored paintings filled with deep purples and blues that often signal the vastness of outer space and the sea. One work shows two astronauts clinging to a piano in the middle of the ocean, not far from fiery wreckage of the Titanic. Another canvas, Constellation Road Map (2018), depicts a car barreling down a wide highway that cuts across a barren desert, with a star formation on a road sign and in the sky above. The paintings exude a whimsical spirit that carries over into the installation.

Oliver Jeffers, The Moon, the Earth & Us, hard-coated foam, steel, and acrylic.

DAN BRADICA/COURTESY OLIVER JEFFERS STUDIO

Jeffers’s works are like onions, he said, with their multiple layers of meaning—though he hardly intends for them be solved like puzzles. He doesn’t want viewers to “follow the clues and unlock some message. All of it comes from this awareness that we’re part of a larger system, and there’s a humility and a responsibility that comes with that.”

On request, however, Jeffers will happily expound. He said the bonfire in The Twelfth (2018), for instance, is a reference to a holiday celebrated in July by Protestants in Northern Ireland, where he was born. The event commemorates the defeat of the Catholic King James II by the Protestant William of Orange at the Battle of the Boyne in 1690. Jeffers said he was interested in the kind of ritualization that attends “relishing in this glorified history.”

Jeffers’s recent High Line installation, which ran through February 7, was called The Moon, the Earth, and Us, and it comprised two globes separated by the distance of a city block—to illustrate the concept of what he called the “overview effect.” The phenomenon experienced by astronauts when they view Earth from space renders borders invisible, and Jeffers said that such dissolution of arbitrary distinctions extends to the art in his Wolkowitz exhibition as well. “A lot of this comes down to narrative and perspective,” he said. “We write ourselves into stories. We connect ourselves to everything.”

[ad_2]

Source link