[ad_1]

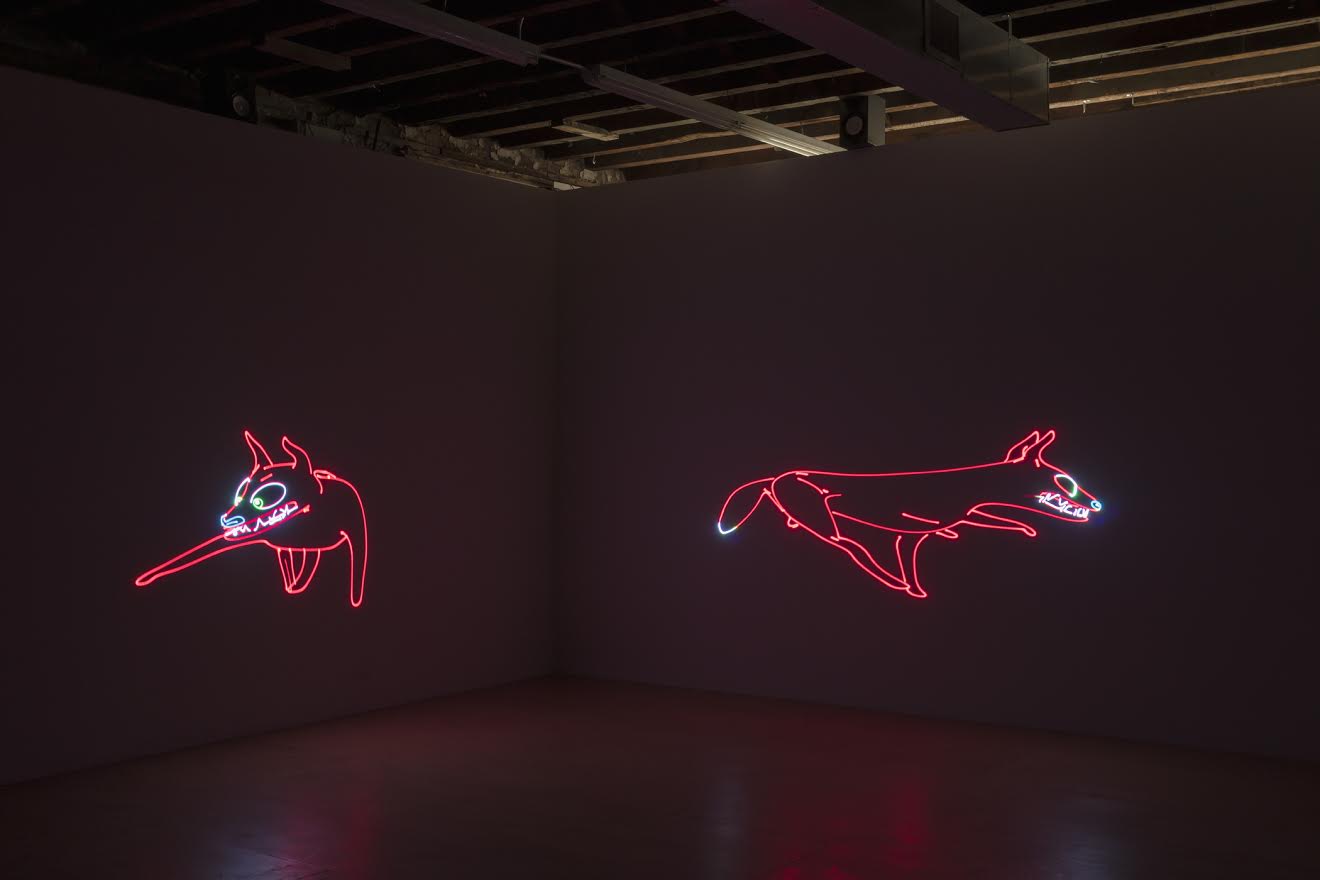

Matt Copson, Down Boy , 2019.

COURTESY REENA SPAULINGS

Slinking furtively, like a predator hunting its prey, over two white walls of Reena Spaulings Fine Art in New York, Matt Copson’s laser-projected dog—imperfectly reflected into two versions of itself, as though ego and id—has a mind of its own. “If the first act is tragic,” a voice that sounds a bit like a Bond villain warns over an intercom, “the audience knows they’re in store for redemption.” Presumably, this foreboding voice belongs to the wild-eyed animal—which also might be a fox—that we see mutate and snarl over the course of its 10-minute monologue. “Bad boy, bad boy! Who raised you, boy?” he chastises himself. But really, the voice belongs to its owner—or creator—Matt Copson, the 26-year-old British artist who has made a name for himself with crisp, bewitching laser projections that have appeared at Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris, and will soon alight in group shows at Sadie Coles HQ in London, Rodeo in London, and the Swiss Institute in New York. ARTnews spoke with him over email for an interview, below, that has been edited and condensed for clarity. Copson’s one-person show at Spaulings, which also incorporates sculptural work, runs at Spaulings through April 7.

ARTnews: What’s your earliest memory of making art?

Matt Copson: I was very into making dens… cardboard castles or big walls of sticks and branches. I’d like to think I’m still doing something similar. I had this one really good den in the woodland where I grew up. They did trench training there during the wars and I would find and collect bits of shrapnel and blown-up gardening equipment.

I ask that because your work seems to be inspired by fables, comic strips, and cartoons. What inspires you about those things?

I like the never-ending quality to fables and serialized comics. Have you read Ed the Happy Clown by Chester Brown? It’s a comic about a clown who’s constantly going through hellish torture. In each comic, Chester Brown would intentionally set up the most complicated, difficult ending to proceed from, with no grand plan as to where the narrative was going. I’ve been thinking about that a lot recently.

I’m predominantly inspired by “Beast Epics” and the way they’ve been passed around to fit the storytellers’ demands or that of the time. I think that’s why I started adapting folk characters; their histories make them more alive than something supposedly new.

Wow, I haven’t read him. Have you read or seen anything else recently that’s particularly felt energizing to you?

I went to Disneyland the other week and remain energized with how formally radical the Pirates of the Caribbean ride is.

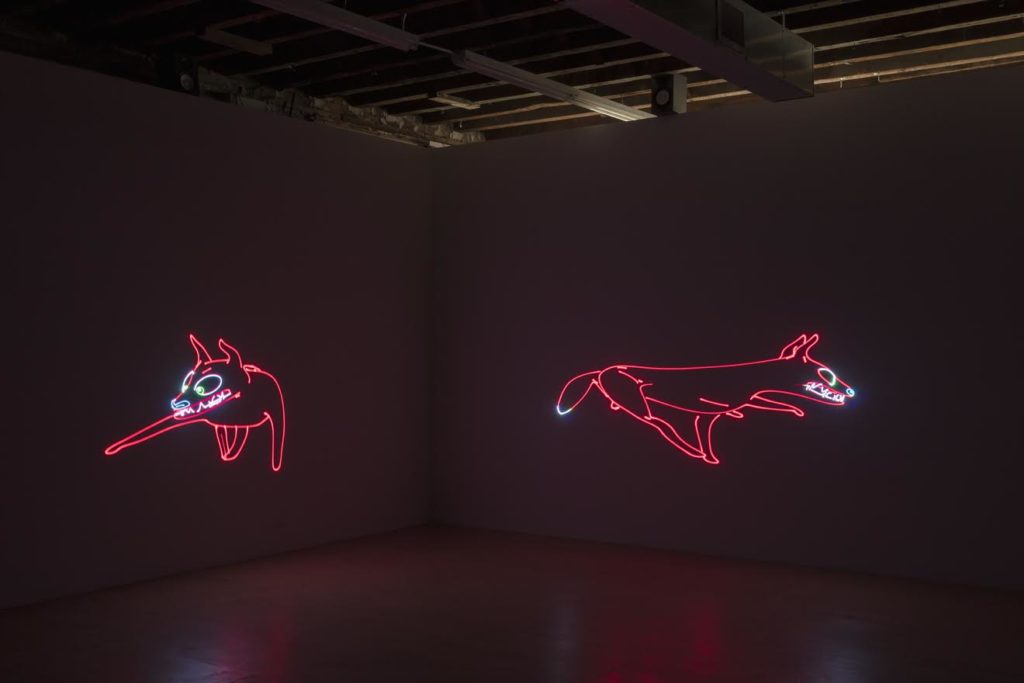

Matt Copson, Down Boy , 2019.

COURTESY REENA SPUALINGS

I love “Down Boy,” your show at Reena right now. I have a lot of questions about it, but first and foremost: How in the hell do you make those projections so fluid and precise?

Well they are laser animations, projected using a mechanical machine just like the ones you find in clubs and festivals. As you saw, they are punishingly bright and visceral and create a line quality and fluidity that is very specific to the form. I think of them more as sculpture than video.

There are also constraints as to how detailed the drawn lines can be, literally how fast the mirrors inside the machine can move, which I really push with Down Boy. I wanted there to be a fight going on between machine and image.

You wrote and voiced the narration yourself, right? What was that process like?

I had this idea about a fox self-inspecting in a mirror, that would be the corner of a room, and followed through with that logic. Then undermining and breaking it. I made an animatic plotting out the actions, and the writing was pretty symbiotic, pulling from lots of my iPhone notes. I recorded and manipulated my voice with [British music producer] AG Cook. It’s a confused soliloquy, unsure which image of itself its addressing—master or pet.

The fox in Down Boy has made appearances in other pieces of yours. What draws you back to this character?

The fox has appeared in almost all of my work. He’s a centuries-old archetype whom I continuously animate and reanimate. Every time I make a new work he changes form almost by himself—in Down Boy he’s an amalgamation of a dog, boy, devil. The fox’s symbolic narrative is so simplified yet unresolved. I wish he could be free… but that’s just not how it works.

You’re working out in Los Angeles currently. What project are you working on there?

Myself, my tan, and new laser work.

[ad_2]

Source link