[ad_1]

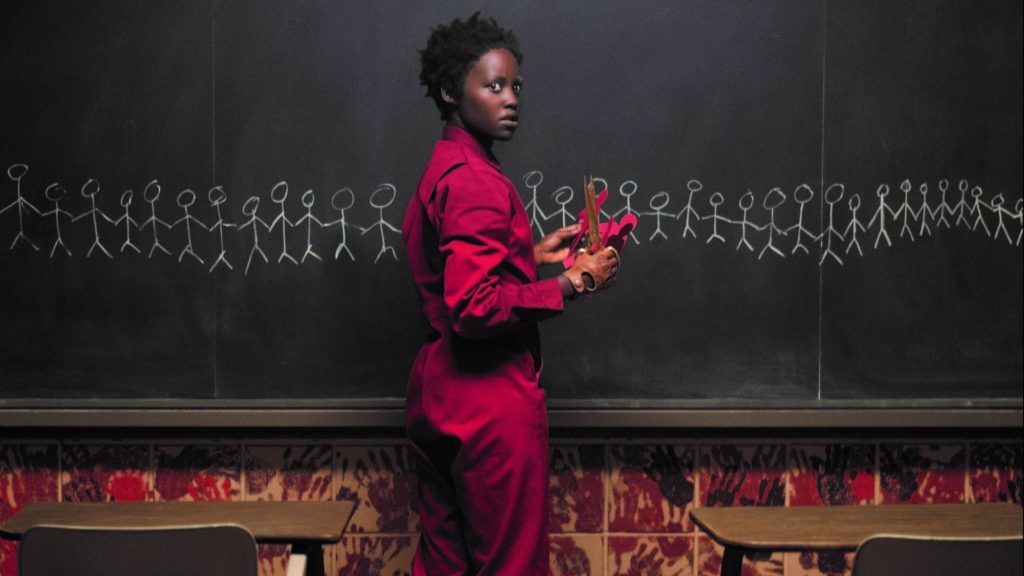

A still from Jordan Peele’s Us, 2019.

CLAUDETTE BARIUS/COURTESY UNIVERSAL PICTURES

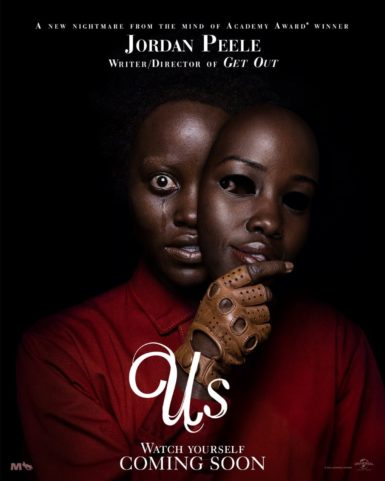

In one sequence in Jordan Peele’s new film, Us, one character, staring at an uncanny image of people serenely clasping hands, says that what he’s seeing looks like “some kind of fucked-up performance art.” He’s not quite right (it’s actually just a sign of evil things to come), but, as it turns out, a performance artist did have a hand in the film’s production.

That artist is Madeline Hollander, whose dance-grounded performances about forms of bodily control have earned her praise among critics and a place in the forthcoming Whitney Biennial. For Us, a film about a family whose beachfront home is invaded by creepy döppelgangers, Hollander supplied choreography, working closely with Lupita Nyong’o to develop the pronounced movements for both of her characters—Adelaide, the family’s paranoid matriarch, and Red, her rage-filled double who has spent her life underground in a decrepit subterranean underpass.

To hear more about Hollander’s role in the film’s production, ARTnews spoke with the artist, whose background in ballet helped her supply the Nutcracker-inspired choreography in one prominent sequence. The conversation, which includes spoilers for Us, follows below. It has been edited and condensed for clarity.

ARTnews: How did you get involved with the film?

Madeline Hollander: I was approached by Ian Cooper, who’s one of the producers on the film. There was a part of the script that was a reference to The Nutcracker. Jordan wanted these dual ballet compositions at the end—one for the underpass and one for the real world. Ian knew that I’d done The Nutcracker a million times growing up. He called me to discuss this scene, brainstorm, go through the script, and make sure that the terminology when the characters are speaking is correct.

ARTnews: Your most prominent work in the film comes toward the end, where a fight sequence between Adelaide and Red is intercut with footage of younger versions of their characters (both played by Ashley McKoy) performing The Nutcracker. Tell me about how you choreographed that.

Hollander: The choreography in the scene is a hybrid, fusing together the Sugar Plum and Cavalier from [choreographer George] Balanchine’s traditional Nutcracker into one solo. It’s both the male and female parts in one dance, and then completely distorted and inverted, almost puppeteered, as if the dancer on the top, in the theater, was dragging around the dancer below via a magnet, through the ceiling.

I met with Jordan to talk about this. I went with a mash-up, kind of Frankensteining clips from my own work, which tends to go into the uncanny or distorted realms. In that conversation, we started talking about all the other kinds of doubling, and it very organically moved into talking about doing movement direction for all the other characters, their tethered versions.

A still from Jordan Peele’s Us, 2019.

CLAUDETTE BARIUS/COURTESY UNIVERSAL PICTURES

ARTnews: The movements of the aboveground characters are often played against those of their underground other halves, or their tethered versions, as they’re called in the film. With Adelaide, for example, her movements are smooth, whereas Red’s are jerky yet still somehow graceful. How did you direct Nyong’o’s movements?

Hollander: It all came from Jordan having really clear ideas of the characters’ personalities. It was really about maintaining the integrity and core soul of the character, but really putting them on opposite realms of something normal or pedestrian. I ended up going through the script and making motion-direction notes for almost every line. Hours into the meeting, Jordan brought in a storyboard artist, and we mapped out the final climax scene and other scenes that had to do with doubling. Lupita was supposed to be an ex-ballet dancer in the film, so she has a specific way of moving. You can always spot who’s been classically trained versus who’s not been. Part of the beginning discussion, after doing the Nutcracker sequence, was: What was it that Lupita would need to do to get trained, so that that would be real?

Lupita moves very gracefully and quietly as Adelaide, and then as Red, she retains this very erect, super rigid ballet spine, and she has a set of movements that are like a Pac-Man meets a cockroach with a book on her head. There’s no balance in Red’s walk. That was developed to contrast the fluidity and movement of this other character, who’s supposed to be motherly.

ARTnews: The movements of the other family members are equally pronounced. Zora (Shahadi Wright Joseph), Adelaide’s daughter, also has a very defined way of moving.

Hollander: Shahadi’s character is an athlete and a teenager, and her double is always pitched forward, on the tip of her toes, ready to sprint at any moment, and just obsessed with Zora—always staring straight at her, always knowing that she could outrun her. It’s just that angle forward, that very slight, five-degree angle forward, that creates this uncanny, creepy vibe.

COURTESY UNIVERSAL PICTURES

ARTnews: It’s interesting how choreographed the motion is for each character, even the background ones without dialogue. Shortly before that climactic fight, there’s a scene meant to mirror the opening, where, in 1986, a child version of Adelaide walks along a boardwalk. Everyone she sees there reappears underground in a flashback, but their movements aren’t quite natural.

Hollander: Everyone on the boardwalk is cast down to the scene below. It was really fun for me to create a signature move [for each character] that would get completely distorted for the underpass—to set all these pedestrian moves in motion and to let them do it until it felt pedestrian. Not something like the typical zombie movie, but something very subtle, like leaning toward one side or stumbling, or only looking to the right while they’re bulldozing forward. If everyone’s doing something even subtly off, it creates this really eerie landscape. That was really exciting, to me.

ARTnews: When you were working on the motions, were you doing it with the actors on set? How did you train them?

Hollander: Over the summer, I auditioned dancers to find someone who could do both ballet and distorted contemporary movement, and also someone who would look like Lupita as a teenager. I was working with Ashley, and I was also working with Lupita, going through the script and working through what the gestures would be—how you would lounge at the beach, how you would sit up or down, what you do after a long car ride. I was training her in ballet—I was going through the basics of what it means to have this training as a background. She did ballet classes every single morning. We looked at references like the witch in Sleeping Beauty, that angular movement. We also did a lot of training where she would move backwards, where she’d be learning to move from her back instead of her front, and a lot of work with her spinal cord, her neck, keeping her shoulders down. On set, I was helping adjust things constantly, making sure there was continuity with the characters throughout the script. A lot of that was improvising with Jordan and the actors.

ARTnews: The attention that’s paid to movement within the film is actually one of the great things about Us. I’ve seen a lot of reviews mention this, which is unusual.

Hollander: Very unusual!

ARTnews: I’ve noticed that there’s a lot of dance in new horror movies. In Annihilation, there’s a very climactic, very choreographed sequence at the end, and there’s of course Suspiria, which focuses on a witches’ coven in a ballet school. Why do you think horror directors have become so interested in dance all of a sudden?

Hollander: That’s a very good question. The body is something that people are paying attention to differently right now than at any other time. What’s interesting is that, in Suspiria and these other films, they’re referencing specific choreographers. In Suspiria, for example, they’re referencing Martha Graham. But one of the things I admired about working with Jordan was that he really wanted everything to be completely new. Even if he was referencing The Nutcracker, it wouldn’t look like Balanchine. It was always a hybrid of many sources, pulling from Michael Jackson’s “Thriller,” The Exorcist, Death Becomes Her. One of the amazing parts of the film is how detailed and nuanced a lot of the movement it is. But you probably wouldn’t notice unless you watched it a few times.

[ad_2]

Source link