[ad_1]

Emil Nolde, Kriegsschiff und brennender Dampfer (Warship and Burning Steamer), undated (ca. 1943), watercolor.

DIRK DUNKELBERG, BERLIN/©NOLDE STIFTUNG SEEBÜLL

On November 9, 1933, German artist Emil Nolde attended what he considered his most important networking event to date: a dinner party with Adolf Hitler commemorating the 10th anniversary of the Beer Hall Putsch, the failed coup in which some 2,000 Nazis in Munich attempted to seize power from the Bavarian government. “The Führer is great and noble in his aspirations and a genius man of action,” Nolde wrote in a letter to a friend after the soiree, noting that Hitler “is still being surrounded by a swarm of dark figures in an artificially created cultural fog.” The “dark figures” to which he referred were Jewish Germans who, the artist believed, sought to destroy what he considered “pure” German art through cultural diversity.

Nolde, then 66 years old, was aware that he was a test case for Hitler and his sycophantic propaganda minister, Joseph Goebbels. Revered as a founding father of 20th-century German Expressionism, he had nonetheless generated controversy among Nazi elites for respectfully depicting a wide variety of subjects, including ethnic minorities. He did not paint in the hyperrealistic style that Hitler preferred, favoring instead bold brushstrokes and electrifying colors to evoke visceral feelings of primal passion.

Emil Nolde in Munich, 1937.

HELGA FIETZ/© NOLDE STIFTUNG SEEBÜLL

But Nolde was determined to enter Hitler’s good graces. A year after meeting at the dinner party, he wrote an autobiography modeled on Hitler’s Mein Kampf—with Nolde’s titled Jahre der Kämpfe (or Years of Struggle, using the plural of “Kampf”). And he advocated eugenics: “Some people, particularly the ones who are mixed,” he wrote in his book, “have the urgent wish that everything—humans, art, culture—could be integrated, in which case human society across the globe would consist of mutts, bastards and mulattos.”

Nolde’s attempts to ingratiate himself with the genocidal Nazi regime did not go as planned. Displeased with his Expressionist style, Hitler featured more works by Nolde than any other artist in his notorious 1937 “Degenerate Art” exhibition (which included 27 of Nolde’s paintings, watercolors, and etchings) and confiscated 1,052 Nolde works from German museums. Stung, the artist retreated to his home in Sebüll, a remote area in Frisia, the northwest region of Germany considered by many Germans to be the cradle of the nation’s language and culture. There, Nolde began crafting an image as a persecuted artist that he promoted to the Allies and his fellow Germans after the war.

It was a farce that most Germans were happy to entertain. As late as 2013, when historian Manfred Reuther published his official biography Emil Nolde. Mein Leben (Emil Nolde. My Life), the 456-page book omitted any mention of Nolde’s admiration for Hitler and condensed World War II to roughly five pages.

Emil Nolde’s Das Leben Christi, from 1911/12, on view in the Nazi’s 1938 exhibition “Degenerate Art” in Berlin.

PHOTO: ©ZENTRALARCHIV – STAATLICHE MUSEEN ZU BERLIN; ART: ©NOLDE STIFTUNG SEEBÜLL

After the artist’s death, in 1956 at the age of 88, the Nolde Foundation (or Nolde Stiftung in German) worked to hide his racist past. But recently the foundation has started to acknowledge the dark side of history—as evidenced by an exhibition at Berlin’s Hamburger Bahnhof museum that opened this summer and remains on view through September 15. “Nolde: A German Legend, the Artist in National Socialism” (the title on display at the museum, as opposed to its online mantle “Emil Nolde. A German Legend. The Artist during the Nazi Regime”) is the first attempt by the foundation to break the German public’s impression of Nolde as a victim of Hitler’s regime rather than an advocate for his anti-Semitic worldview.

For many years, Bernhard Fulda and Aya Soika, a husband-and-wife team well-respected in the international art research community and co-curators of the show with Christian Ring, the head of the Nolde Foundation, tread a fine line with Nolde’s legacy. Though they have published numerous articles shedding negative light on the artist—most notably a 2014 catalogue essay for an exhibition at Neue Galerie in New York—they have done so with caution. “For decades, the foundation did really sit as gatekeepers on all this archival material,” Fulda told ARTnews. “Access to his written legacy has been notoriously difficult.”

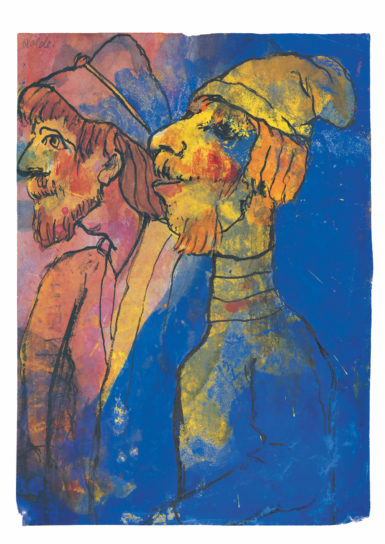

Emil Nolde, Gaut der Rote, undated (ca. 1938), watercolor and India ink.

DIRK DUNKELBERG, BERLIN/©NOLDE STIFTUNG SEEBÜLL

That changed when Ring took over in 2013, ending a long history of what Fulda called “the artist’s marketing campaign,” and the exhibition marks the first time Nolde’s racist views have been fully exposed. To expedite the transparency, the exhibition’s hefty catalogue has been published in both German and English, a bilingual gesture often avoided with controversial German exhibitions.

The show opens with Pentacost (1909), a painting that fueled Nolde’s anti-Semitism when it was rejected for an exhibition by the Berlin Secession, an artist group founded in 1898 in opposition to European salons and as a defender of traditional German culture. Nolde was deeply attached to the work depicting the visitation of the Holy Spirit upon Jesus Christ’s apostles after their savior’s death and resurrection, and after its dismissal he wrote a scathing letter to Berlin Secession president Max Liebermann that leaked to the press, much to Nolde’s horror. The episode, according to Fulda and Soika, led Nolde to give serious weight to the idea that Liebermann, a Jewish German, and what Nolde called the “Jewish-dominated” press were subverting true German culture. “Throughout his life Nolde suffered from negative art-criticism,” the researchers write in the exhibition catalogue, “and in this anti-Semitic conspiracy theory he found something it could be convincingly attributed to.”

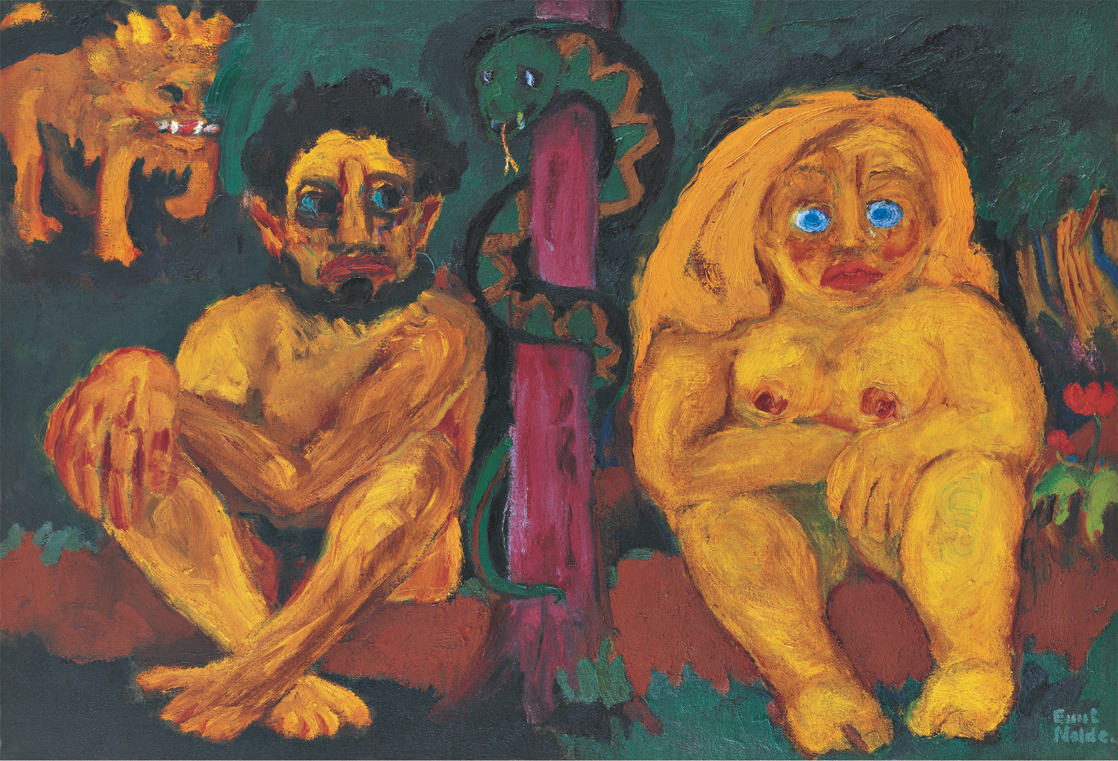

Rather than deflecting the subject of anti-Semitism by focusing on Nolde’s most iconic works, including his nine-part 1912 masterpiece The Life of Christ, the curators chose to focus on art by Nolde that reflects the racist myth of Nordic superiority in which he believed even after the Nazis rejected his work. In 1938, Nolde created the luminous blue and golden watercolor Mistress and Stranger as part of a series celebrating vikings that counted as a failed attempt to have Hitler reconsider his fate when he refused to paint the Nordic subjects in the realistic hues that the Führer preferred. In Three Old Vikings, a trio of warriors are fierce and ready to fight—but unusually colored in fiery burnt orange and saffron. In Veterans, two soldiers stare out with stoic, determined faces and clenched jaws, yet Nolde thwarted his mission once more by painting their skin an odd golden hue.

After the war, Nolde touted these and other works as a sign of his bravery against the Nazis—a position thoroughly debunked by the exhibition. A quote from Nolde’s wife Ada prominently displayed in the Hamburger Bahnhof boasts that the couple had stood “fully and completely behind our Führer” long after other Germans had denounced him. And a lengthy essay in the catalogue (and excerpted in the exhibition) analyzes the anti-Semitism in Nolde’s Jahre der Kämpfe.

Emil Nolde, Verlorenes Paradies (Lost Paradise), 1921, oil on canvas.

FOTOWERKSTATT ELKE WALFORD, HAMBURG, AND DIRK DARK MOUNTAIN, BERLIN/©NOLDE STIFTUNG SEEBÜLL

“He is an artist we would not normally celebrate: an anti-Semite, someone who joined the Nazi party and who for the rest of his life never apologized,” Fulda said. The previously predominant view of Nolde as a wartime victim owed much to the Nolde Foundation’s tight grip on his reputation, and it was also influenced, Fulda said, by the fact that many past historians, curators, and journalists might have not wished to offend living relatives who may have been admirers of the Nazi regime themselves.

But all the recent research has started to lead to change. Earlier this year, German Chancellor Angela Merkel removed Nolde’s Breakers, a striking 1936 seascape, from a prominent place on her office wall. And revelations about the artist’s past of the kind on display in Berlin may stand to change thoughts about his work forever. “Whenever people think that art and cultural context are entirely distinct spheres—[that] art is totally autonomous—they are kidding themselves,” Fulda said.

But Fulda and Soika’s role as historical researchers is only part of an equation that includes viewers, too. “We don’t pass any judgment in that regard,” Fulda said. “We don’t say, ‘This is what you should do with this cultural context.’ We tell art lovers: ‘Deal with it—now you figure out how this new knowledge frames the artworks of Nolde that you’re seeing.’”

[ad_2]

Source link