[ad_1]

As hundreds of thousands of people take to the streets demanding the defunding of police departments, the end of anti-Black racism, and justice for George Floyd, Tony McDade, Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, and Rayshard Brooks, it is important to remember that the seeds of the police and prison abolitionist movement were planted long ago, as far back as the struggle to end slavery. In recent decades, Black women have tended these seeds by developing the conceptual framework for the movement (think Angela Davis, Ruth Wilson Gilmore, and Mariame Kaba) and by performing the care labor of holding together communities that have been convulsed by mass incarceration.

Nicole R. Fleetwood’s new book, Marking Time: Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration, centers on the care labor and everyday activism of Black women who do the work of abolition by maintaining relationships with family members and loved ones who are incarcerated, including the women in her own family who showed up for the young Black men who had been sent to prison. The book, whose release was scheduled to coincide with a MoMA PS1 exhibition that has been postponed, is a thoroughly researched and heartbreakingly personal look at prison art and the broader visual culture of incarceration, and the way art becomes a mode of relationality among prisoners who use it to combat the imposed isolation of imprisonment. Rather than analyzing prison art as “outsider art” or as a form of therapy, Fleetwood uses the term “carceral aesthetics” to describe how penal space, time, and matter shape the production of the art she examines.

The peculiarities of the institutional context of the prison are familiar to those who have a loved one in prison or have been in prison themselves. Incarcerated artists create under conditions of extreme duress. Their supplies are limited to what they can purchase through the commissary or access through arts programs (which, if available at all, are usually restricted to prisoners with no disciplinary records). Certain paint colors are banned (due to their chemical composition) and the kinds of items prisoners can possess are strictly regulated. Prisoners are always being watched. The content of the work they produce, what they can say to outside collaborators, and how they circulate their work are censored or mediated by prison administrators. And yet they still create art—often compulsively, sometimes using contraband materials or repurposed trash. Art can also be a means of survival for prisoners who trade it for food, services, or commissary items.

Courtesy Jesse Krimes

What I especially appreciate in Fleetwood’s book, in addition to the attention she pays to the material dimension of carceral aesthetics, is her insistence on examining how power structures both the conditions under which incarcerated artists work and how their work circulates. She examines the power dynamics between established artists on the outside who seek to collaborate with prisoners (a prison administrator recounts that one incarcerated person who had been asked to participate in such a collaboration responded, “They are using us”), the state’s punitive deployment of mug shots, and even the power imbalance between incarcerated artists and well-meaning prison arts programmers. While nonprofits might try to quantify the salutary effects of prison arts programs to convince funders that art facilitates “rehabilitation,” Fleetwood is keenly aware that this model pathologizes prisoners and leads to an individual-based, rather than a structural, understanding of the question of why people end up in prison. She traces the history of prison arts programs back to their revolutionary roots, starting with the collaborations between Black arts organizations and prisoners in the late 1960s and early 1970s, particularly in the immediate aftermath of the 1971 Attica prison uprising. Groups like the Black Emergency Cultural Coalition—which was founded in New York in 1969 by Benny Andrews, Romare Bearden, Faith Ringgold, Camille Billops, Norman Lewis, and others—pivoted toward organizing prisoners in the 1970s and engaged in art collaborations with prisoners as part of their broader struggle. Yet many of these programs collapsed after Ronald Reagan banned prison arts programs from accessing NEA grants.

Courtesy Dean Gillispie

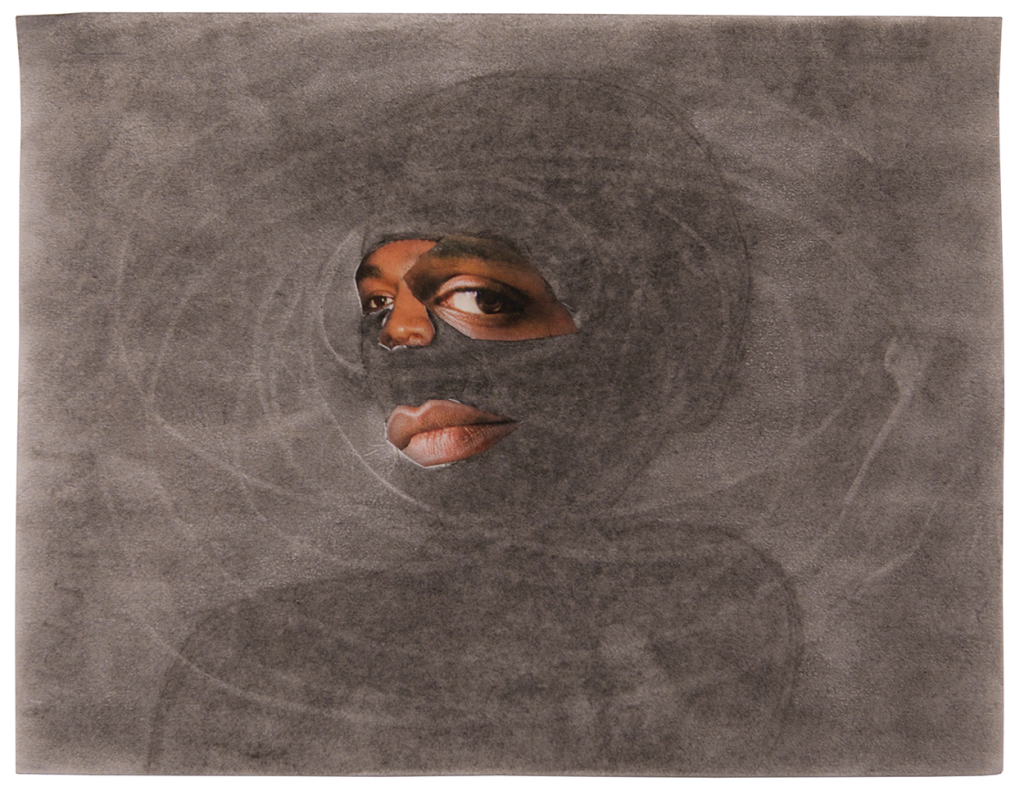

Woven throughout the book are striking illustrations of the work of incarcerated and formerly incarcerated artists, and, occasionally, art by non-incarcerated artists that engages the subject of prisons. The works are wide-ranging: Gil Batle’s Sanctuary (2014) is an ostrich eggshell into which brutal scenes of prison life are intricately carved; Dean Gillispie’s Spiz’s Dinette (1996) is a miniature model of an Airstream diner made from materials including notebook backs, cigarette foil, and popsicle sticks; Tyra Patterson uses hair, cloth, glitter, and other materials to make three-dimensional portraits of incarcerated women, accompanied by symbols from nature. Some of the works are massive, such as Jesse Krimes’s fifteen-by-forty-foot work Apokaluptein 16389067 (2010–13), which consists of images transferred onto prison bedsheets and was assembled only after Krimes was released from prison. Other works are more muted and seem to emanate from a place of deep melancholia, such as Billy Sell’s haunting black-and-white self-portrait made the year before he was found dead in his cell while being held in long-term solitary confinement (his death was ruled a suicide, but activists have questioned this conclusion).

The first four chapters of the book cover an impressive breadth of topics, including the racist origins of Kantian aesthetics, “mushfake” (makeshift tools and objects made by prisoners, such as a tattoo gun created out of an electric razor and other items), photographs of prisoners done in the social documentary mode, and the aesthetic and symbolic functions of portraits produced by prisoners. The final three chapters, which address collaborative art in prison, art produced in solitary confinement, and vernacular prison photography, hit hard on an emotional level. In the last chapter, Fleetwood includes images of herself and her family members posing with her cousins Allen and De’Andre in prison. She reflects on these photographs and on the millions of prison photos that circulate between incarcerated people and their loved ones: the pain of noticing an expression of resignation, or seeing the incarcerated person and yourself age in the images.

As someone whose brother has been incarcerated for sixteen years (of a life sentence that was commuted to forty years), I found this chapter deeply moving. When Fleetwood describes her dread upon receiving pictures from her incarcerated cousin Allen because she found them so emotionally overwhelming, that response felt familiar. While reading this book, my brother mailed me a thick envelope of pictures. He had just been put in Close Management, was transferred to a higher security prison for contraband found in a windowsill (which he insists wasn’t his), and faced new restrictions on what he could possess, prompting him to send his collection of photographs to me. I felt deeply saddened by the photographs from our childhood. There was one of him posing with our childhood dog, another of me graduating from high school, selfies of my adolescent best friend and others from our high school, photos of my Dad’s car, and some photos I must have sent him over a decade ago of a trip to Italy. What does a photograph mean to someone who is incarcerated?

Courtesy Tamms Year Ten

That is a question taken up in an ongoing program that Fleetwood discusses, Photo Requests from Solitary, which was initiated by a grassroots coalition that fought to shut down Tamms Correctional Center, a supermax prison in Illinois that did eventually close, in 2013. People held in long-term solitary confinement can request photos of anything—real or imagined—that non-incarcerated volunteers then take or digitally produce for them. As Fleetwood notes, this program enables the co-construction of a “collective imaginary” beyond the brutal imaginary of cages. Roberto, writing from Tamms, asked for “an alternate background from the IDOC [Illinois Department of Corrections] picture. I have no pictures of myself to give my friends and family. . . . If you can place my picture on another background. Nothing too much please. Something simple like a blue sky with clouds or a sunset in the distance.” While prisoners have been largely excluded from public life, the art and images Fleetwood highlights function as material traces of the disappeared, who, through acts of creation, refuse to be rendered invisible.

[ad_2]

Source link