[ad_1]

A Jeff Koons at Gagosian’s booth, which has pieces by Ed Ruscha, Andy Warhol, and more.

PHOTOS: ANDREW RUSSETH/ARTNEWS, EXCEPT WHERE NOTED

The parties may have been raging last night—particularly White Cube’s on the beach in front of Soho House, which went into the wee hours and had revelers splashing in the Atlantic—but collectors seemed to be awake and alive enough today at the VIP preview for the 17th edition of Art Basel Miami Beach.

The sales began bright and early at 11 a.m. at the city’s convention center, which has just completed a $615 million renovation. Dealers had mixed opinions about the crowd—a few reported seeing fewer Europeans this year—but business seems to have been steady.

And there were, to be sure, big collectors on hand, like Martin Z. Margulies, Maja Hoffman, and the Eisenbergs. The museum and nonprofit folks were out in force, from curators Ian Alteveer of the Metropolitan Museum of Art and Stuart Comer of the Museum of Modern Art to Guggenheim director Richard Armstrong and NSU Art Museum Fort Lauderdale director Bonnie Clearwater to Performa founder RoseLee Goldberg and Jasmine Wahi of Project for Empty Space in Newark, New Jersey. And there were no small number of artists, like Stanley Whitney, Eric N. Mack (who has an elegant booth with Los Angeles’s Morán Morán), Borna Sammak, Natalie Frank, Chuck Close, Charles Gaines, and Duke Riley in a pork pie hat, a tall feather launching from its brim.

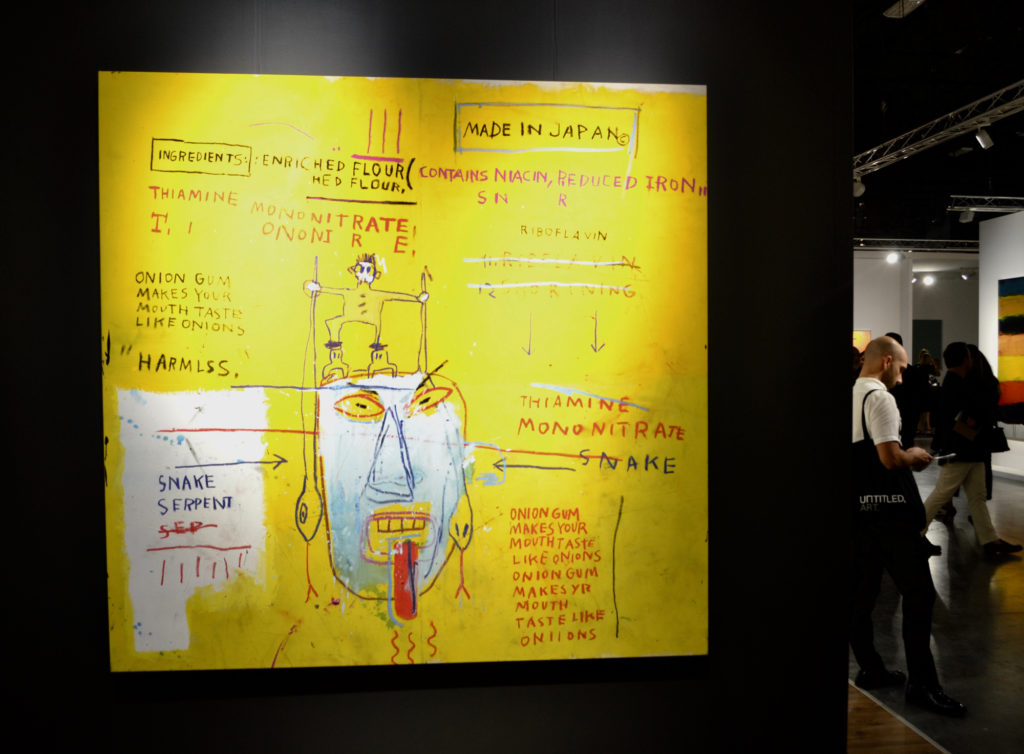

The talk of the fair was the $50 million Rothko being offered by Helly Nahmad, the kind of number more associated with the fair’s Swiss edition, though it was not the only eight-figure offering today. Blue-chipper Van de Weghe had Jean-Michel Basquiat’s bright yellow 1983 Onion Gum for a cool $16.5 million. It traded a little more than six years ago in a contemporary evening sale at Sotheby’s New York for less than half that, $7.36 million, but the market for the late artist’s work is hot. Measuring just about 80 inches square, the piece was originally sold by Mary Boone and Bruno Bischofberger, and has an angry white face near its center, a red tongue juts from its mouth.

Works by Keith Haring at Gladstone Gallery’s booth.

COURTESY GLADSTONE GALLERY

A Haring Doubleheader

Lévy Gorvy did a booth dedicated to the 1980s and riffing on the Lower Manhattan Pop Shop of Basquiat’s famous friend Keith Haring, down to wallpaper from the store and directors wearing hand-painted Pop Shop-inspired sneakers. A Haring wall sculpture on the outside of the booth, Untitled (burning skull), was priced at $3.5 million, a step up from the $965,000 it made at Sotheby’s back in 2013. The booth’s focal point, Haring’s iconic, triangular 1988 painting Silence=Death, priced at $8.5 million, was “under serious discussion” by day’s end, according to a director.

In what came across as something of an aggressive move but might have been sheer coincidence, Lévy Gorvy’s Haring-heavy display (inclusive of another sculpture and a table) was presented right next to the booth of Barbara Gladstone, who represents the Haring estate, currently has a Haring exhibition on at her New York gallery, and did a whole mini-exhibition in her booth of a handful of rare-to-market works by Haring, including painted screens, glass windows, a terracotta vase, and a Japanese lamp. All’s well that ends well, though: toward the end of the day, Gladstone sent out an email to press indicating that all of the pieces in that special Haring presentation had sold, for prices ranging from $300,000 to $1 million.

Works were moving. Just a few hours into the fair, New York’s Kasmin gallery had sold pieces by Alex Katz, William N. Copley (the subject of a very strong focus show just across the water at the Institute of Contemporary Art in Miami), and Lee Krasner, the latter a painting from 1963 that went for $3.6 million. Among the big-ticket items in its booth was a lively 1970 Frank Stella with a price tag of $3.85 million. Miami Basel, Kasmin director Nick Olney said, is always the gallery’s best fair of the year.

By late afternoon, New York’s Van Doren Waxter was reporting more than a dozen sales, for prices up to $100,000, of pieces by Jeronimo Elespe, Dorthea Rockburne, and Brian Rochefort.

At New York’s Michael Rosenfeld Gallery, red dots denoting sales sat atop the labels for works by Alma Thomas and Joan Mitchell. A sumptuous large sculpture by Barbara Chase-Riboud was priced at $700,000, and a smoky Lee Bontecou drawing was marked at $480,000.

Mitchell Mania

This past May, Mitchell’s 1969 painting Blueberry brought in $16.6 million at Christie’s New York. Following that sale, Mitchell paintings popped up at multiple galleries at Art Basel in June. Hauser & Wirth sold a 1969 Mitchell painting, Composition, for $14 million; David Zwirner sold a 1958 untitled painting for $7.5 million (reportedly to an Asian collector); and Lévy Gorvy sold an untitled painting from 1959 for $14 million. Van de Weghe sold a large, later Mitchell painting—No Room in the End (1977)—but did not disclose a price.

But Mitchell’s last two record prices at auction, before Blueberry blasted through, were achieved by large paintings from 1960. In 2011, at Sotheby’s New York, a 95-by-78 inch one brought in $9.3 million, soaring past a high estimate of $6 million. And in 2014, a large (98-by-80 inches) untitled 1960 painting made $11.9 million at Christie’s, New York. Last month, Mitchell’s large (116.4 in.; Width 78.7 in.) 1960 painting 12 Hawks at 3 O’Clock sold at Christie’s New York as part of the Barney Ebsworth collection for a squarely within-estimate $14 million, and the 1960 Mitchells were out at Art Basel in Miami Beach: Cheim and Read, which used to represent the artists’ estate, has a small one priced at $1.5 million. David Zwirner, which earlier this year began representing the artist’s estate, has a small one priced in the range of $5 million to $6 million, which appeared last month in Cheim and Read’s exhibition “Joan Mitchell: Paintings from the Middle of the Last Century, 1953–1962.” All of the paintings in that show were from private collections; interestingly, the one now on Zwirner’s booth was not for sale in the Cheim & Read show. And Mnuchin has a small one (26 1/8 by 29 inches), which last sold at auction in 1997, at Christie’s, New York, where it made a within-estimate $68,500. At Mnuchin it’s priced at $2 million. White Cube also has a small (28-by-28-inch) untitled Mitchell from 1960, heavy on the color green, priced at $1.5 million. It last sold at Sotheby’s New York in 2015 for a within-estimate $466,000.

Berggruen and Edward Tyler Nahem, whose booths were around the corner from each other, have Mitchells from the end of her career, Berggruen a vibrant one from 1989, and Nahem a very large painting from 1992, the year of Mitchell’s death, priced at $5.5 million.

None of the aforementioned Mitchells had sold by day’s end.

Basquiat’s Onion Gum (1983), on offer for $16.5 million at Van de Weghe.

Star Power

Still, sales seem to have generally been robust. Mnuchin—which laudably had only one piece by a white male artist on the booth (a Sean Scully painting)—sold pieces by Mark Bradford, El Anatsui, and Ed Clark, in the range of $250,000 to $2.5 million.

Also in the high-price-tag category were works on the booth of Thaddaeus Ropac, who parted with many of them and called the day “solid.” One of the pieces that sold was a huge new painting by Georg Baselitz, Die Barrikade, featuring the artist’s trademark upside-down figures, for $1.7 milion.

At least one observer reported seeing Leonardo DiCaprio wandering the aisles, but star power in a different form was at Acquavella’s booth in the form of a 1981 Basquiat self-portrait from the collection of Johnny Depp. A paint and paper collage on three wooden panels, it came up for sale at Christie’s London in 2016 as part of a group of works from Depp’s collection. It was estimated then at £1 million to £1.5 million. It sold at that sale for £3.55 million. Acquavella has it on offer in the region of $9.5 million. Much more recently on the block is the Roy Lichtenstein painting in Acquavella’s booth. The bright and sexy Still Life with Head in Landscape, from 1976, sold at Sotheby’s just this past May as part of a group of works from the collection of Morton and Barbara Mandel, who had bought it from Pace Gallery way back in 1992. It made $10.5 million. Acquavella is selling it for a client who bought it at the Sotheby’s sale, priced in the region of $14 million.

Occupying prime real estate in Hauser & Wirth’s booth is a late sculpture by David Smith, on offer for $18 million. The painted steel Zig I, from 1961–64, is part of a group of major late Smiths, a series of seven of which six are in museums. This one is the last in private hands. Hauser & Wirth, which has represented the Smith estate for the past two years, says the sculpture is on consignment from a private collection. The piece has a Miami connection: it was once in the foundation of local heavyweight collectors Irma and Norman Braman. Sotheby’s sold it in 2016 for $10.5 million against an estimate of $8 million–$12 million. At Miami Basel, the piece had not yet sold on opening day.

A Mark Bradford that sold for $5 million at Hauser & Wirth.

But Hauser & Wirth had a handful of high-value sales. A 1976 Philip Guston went for $7.5 million, a 1969 Guston went for $2.75 million to a European collection, and a new Mark Bradford painting, Feather, went for $5 million as a promised gift to an American institution. Notably, a brand new painting by Amy Sherald, known most recently for her striking portrait of Michelle Obama, sold for $175,000 and is a promised gift to an American museum.

Museum Shopping

Those looking to do some shopping based on museum shows could do so all over the fair. Mexico City and New York’s Kurimanzutto and London’s Sadie Coles HQ, for instance, were both offering sculptures by the British master Sarah Lucas, who’s the subject of a deliriously fun, and generally well-reviewed show at the New Museum in New York. (The latter gallery was showing a pair of tall concrete boots; it was, understandably, a popular place to have one’s photo taken.)

Meanwhile, New York’s Peter Freeman had text paintings by Mel Bochner (“MISTAKES WERE MADE,” one reads) like those currently on view at 2018 Carnegie International in Pittsburgh. And Sarah Crowner and Jeremy Deller, who also appear in the exhibition, have works at, respectively, Nordenhake and The Modern Institute/Toby Webster.

Virginia Jaramillo, a standout in “Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power,” which is now at the Brooklyn Museum, has three brilliantly colored abstractions from the 1970s at Hales of London and New York, each priced at $230,000.

At Perrotin, five pieces by Paola Pivi sold for between €40,000 and €110,000 (about $45,000–$115,000). “We are very happy with the presentation of her work,” said Emmanuel Perrotin, clad in his signature seersucker jacket. (She’s also the subject of a solo show at the Bass museum, a few blocks away from the convention center.) Another piece by Pivi, the large-scale installation of a floor-to-ceiling wheel of bear-skin rugs titled What goes round — art comes round (2010) was available for €220,000 ($250,000).

Jane Cohan of James Cohan Gallery, which is based in New York, reported three mirror pieces of various sizes by Xu Zhien were sold in a range of $45,000 to $60,000; its biggest sale of the day was a painting by Tom Aselli for $575,000. “Basel is consistently a good time for us,” she said. “We’ve been coming here since the beginning.” Also sold at James Cohan Gallery was Mernet Larsen’s vibrant, minimal Conversation for $65,000, a piece by Trenton Doyle Hancock for $100,000, and two Elias Simes, both composed of found pieces of computer motherboards arranged into mosaic.

Zwirner sold numerous works on opening day, including an Oscar Murillo painting for $380,000, and a Harold Ancart painting for $150,000, the latter of which could have sold many times over, according to one Zwirner director.

Lehmann Maupin reported the sale of a piece by conceptual artist Teresita Fernández within the range of $240,000–$260,000, as well as a large-scale installation by Liza Lou for $150,000–$200,000. Also sold through the gallery was a piece by Nari Ward in the range of $140,000-$160,000; Ward will have a solo exhibition, “We the People,” at the New Museum opening on February 13, 2019.

Galerie Gmurzynska’s Isabelle Bscher said that Roberto Matta’s Les Témoins de l’univers for “around half a million dollars.” Asked about who’s been coming by the stand, she said, “I’ve seen a few of the same collectors [that consistently have come in past years], but definitely not everybody.” By day’s end they’d also sold works by the Haas Brothers and Louise Nevelson.

Two neon works by Mary Weatherford sold at David Kordansky’s booth for $225,000 each, as well as Rashid Johnson’s Untitled Microphone Sculpture (2018), which sold for $235,000. A work by Huma Bhabha (who’s also in the 2018 International) sold for $150,000, and the much-buzzed about Lauren Halsey sold a piece for $40,000. Among Kordansky’s early sales was also a Jonas Wood titled Blackwelder Speaker Still Life (2018), which sold for $450,000.

Pace was offering a curated booth, “Lightness of Being.” “This year has been really different for us because we have such a focused presentation,” Hanna Gisel, the gallery’s press director, said. “It’s not like we have something for everybody on the wall.” James Turrell’s Untitled (XXXII G), 2014, sold for $150,000, Mary Corse’s Untitled (Electric Light) (1968/2018) for $180,000, Larry Bell’s untitled glass/mineral sculpture from 1970 sold for $250,000. (Bell’s the subject of a taut survey show at the ICA Miami.)

White Cube’s Jay Jopling, meanwhile, confirmed the sale of a sculpture by Antony Gormley for £350,000 (or about $446,000). The piece, DAZE VI (2016), stands towering in the middle of the booth as a sort of brick-colored centerpiece.

Josh Lilley Gallery’s offered a selection of works by Derek Fordjour in the “Nova” section, which focuses solely on work that was made within the last three years. The booth sold out for an estimated total of $350,000, each piece selling for between $26,000, $48,000.

The Memphis-born artist uses newspapers instead of canvases in his paintings, which looked wonderful within the booth’s ramshackle design—the gallery had swapped out the standard white cube for rusted tin slats and a gravel floor. Donna Marie, who co-designed the space with the artist, said, “He wanted to give more context to the painting” and point out “the disconnect between the art world and the real world.”

Andrew Russeth contributed reporting.

[ad_2]

Source link