[ad_1]

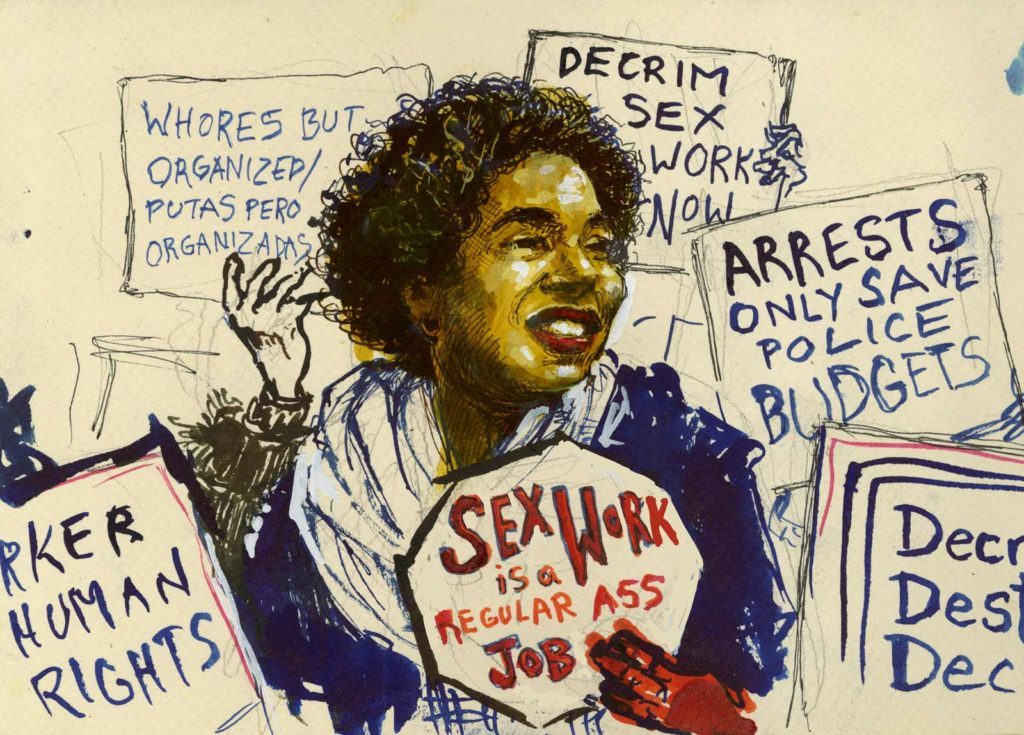

Before the coronavirus pandemic shut down the Sex Workers’ Pop-Up in March, just two days after it opened, New York was able to glimpse artwork that spoke to the experiences of fierce fighters in a field that has been subject to ongoing stigma and criticism. “When your very existence is criminalized, survival becomes a radical action,” read text included as part of an installation of black-and-white portraits of black and brown, cis and trans women by photographer Kisha Bari. Alongside it were Molly Crabapple’s drawings of Decrim NYC for the defunct sex-worker magazine $pread, video interviews with South African sex workers by Candice Breitz, performance photos by Annie Sprinkle, and a canopy of red umbrellas—the international symbol of the sex workers’ rights movement—by Sun Kim.

Such a moment of celebration and call for action by the sex workers’ rights movement was cut short by the coronavirus, which has created a new existential threat to those who cannot afford to stop working during the crisis and have no access to resources available for other service-industry professionals. Sex workers who also have careers in the art world, whether as artists or muses to creators, have remained resilient, continuing to produce important work during a time of crisis.

The Sex Workers’ Pop-Up, where 17 of the 22 presenting artists had backgrounds in sex work, was intended partly to underscore that many sex workers are artists and that there are artists who are sex workers. As the exhibition showed, sex work and art have a long, intimate history, especially in kink-friendly niches, because both can be considered areas that push at social boundaries through creative means. Beyond the possibility of providing for elemental material needs, consensual sex work can provide artists with an auxiliary creative outlet and inspiring insights into the human condition.

“We are much more than bodily barometers for the toxicity levels of the patriarchy,” Bella, a London-based artist and sex worker has written. “We can be its bailiffs too, knocking down its doors and seizing the cash up front. Leaving furnished with its fruits, empowered and enriched.”

Isaac Garcia

Yet the pandemic has changed the way sex workers do business, and among the mortal dangers Covid-19 creates for sex workers are infection, increased predation, and financial destitution. Since the virus’s emergence, sex workers were among the first to experience the massive loss of employment now devastating many other sectors, due to the closing of strip clubs and concerns from clients about interpersonal contact. Even legal sex-workers were explicitly excluded from eligibility for Covid-19 relief loans for business and the self-employed.

These moral prejudices divide sex workers with pre-existing online platforms and those without. “People need porn right now, and our company provides a small amount of gigs to sex workers—though obviously, not to the ones working on the street, without any internet access, who are suffering most right now,” said Stoya, a pornographic actress and founder of ZeroSpaces, who collaborated with the artist Clayton Cubitt on a 2014 projects that is more relevant than ever. “Hysterical Literature”, a video series on YouTube, shows artists, scholars, porn actresses (including Stoya) and writers orgasming from his remote-control sex toy play while reading their favorite pieces of literature. “Hysterical Literature” speaks to a need for intimacy right now—something that artists and sex workers can provide.

Risks still exist on the digital sphere, however. Leah Schrager—who also works under the guise of Ona, a cam-girl persona/conceptual artwork—said that, while sex work can provide all kinds of relief for viewers and customers with wit and wiles, earning a sustainable living during the pandemic without a pre-existing following, identity, and platform can be challenging, especially with a significant surge in performers and equal drop in viewers’ tips. “It’s obviously a super challenging time, but I would encourage those who start doing online sex work to do it because they’re really into it,” Schrager said. “Just like any job, a true enjoyment and passion for it really helps for the long run and the overall experience. I’ve personally always thought of online sex work as an awesome thing—but there is massive societal prejudice against it.”

Scams preying on novice cam-girls are proliferating. Rachel Oyster Kim, who left a top-tier art school for full-time sex work, said that she urges potential cam-girls to consider the likelihood that content will be recorded and rereleased. “You never know who is recorded,” Kim said, “and you have limited ownership over your own content.” For the clients and creators, cam-work can provide needed parasocial connection along the lines of the tag-line for eighties porn-star and AIDS activist Robin Bryd’s iconic Public Access show, when she urged viewers to avoid risky sex and instead stay home with her.

Courtesy the artist

Preexisting health issues can also pose issues. “Many sex workers are immune-compromised and battled chronic physical or mental illnesses, or are primary care-givers for vulnerable loved ones, because sex work can provide flexible working hours and a healthy income, although it does not provide health care. And whenever this happens, the predators come out,” Arabelle Raphael, who appears in paintings and etchings by artist David Nicholson, said. And one visual artist and sex worker who is living off savings in self-quarantine said, “I’ve found it downright depressing that [clients] are trying to haggle rates lower because of ‘these uncertain times’ and pressure for bareback assuming I’ll do anything for cash now.”

To help sex workers in need, sex-worker-run organizations and networks are fighting to provide emergency funds and forums for sex workers’ voices, despite the constraints of the FOSTA-SESTA law on sex workers’ various forms of expression. GoFundMe pages have been set up across the country by the Sex Workers Outreach Project (SWOP) with the Emergency COVID Relief for Sex Workers in New York page. So far, it has raised $113,203 of its $125,000 goal.

For allies in the arts, donations to fundraisers help sex workers survive the crisis and continue fighting for “rights not rescue.” Candice Breitz, an artist whose work is currently the subject of a virtual exhibition put on by the Baltimore Museum of Art, emphasizes the need for continued multi-leveled support alongside digital fundraising campaigns. Breitz has long focused on sex work in art, and in her work for the Sex Workers’ Pop-Up, she focused on sex workers in Cape Town, South Africa. She is currently working to raise survival funds for the “precious and precarious community of those sex workers.

“The majority of sex workers live precarious lives, even at the best of times,” she said. “For many of us, this virus—which has forced us to radically reconsider how we engage with the world—has created various levels of inconvenience, loss of income, loss of stability. But of course those who are affected the most severely and most brutally by the pandemic are those who must weather this crisis without the set of social and legal protections that are afforded to many of us as ‘human rights.’”

Below, see a new video by artist Leah Schrager. This video contains sexual content. Viewer discretion is advised.

Leah Schrager, “Quarantine & Chill” Starring @OnaArtist, 2020.

Courtesy the artist

[ad_2]

Source link