[ad_1]

Deborah Kass, After Louise Bourgeois, 2010, neon and transformers on powder-coated aluminum monolith.

© DEBORAH KASS/COURTESY THE ARTIST

A few weeks ago, Phillips auction house in New York installed the exhibition “Nomen: American Women Artists 1945 to Today,” curated by former Brooklyn Museum director Arnold Lehman, who joined Phillips as a senior adviser four years ago. The exhibition, which runs through Saturday, August 3, consists of 70 works, including ones by Kay Walkingstick, Jaune Quick-To-See Smith, Betye Saar, Janine Antoni, Kiki Smith, Patricia Cronin, and Deborah Kass.

ARTnews Editor Sarah Douglas had a casual chat with Lehman in his office at Phillips a few weeks before the show opened, while he was finalizing it.

ARTnews: You can only include around 70 artists in this show. How many were on your original list?

Arnold Lehman: About 300. It’s hard to draw lines because I want to make this singularly an important event in terms of a kind of summation at the end of this decade of that period of 75 years. It’s also the hundredth anniversary of the nineteenth amendment, and I think it’s important to look back at that and to see where we are today, where finally women have a strong and often a leadership place in the visual arts.

AN: Your exhibition starts in 1945, but in your research you were looking much earlier?

AL: At the beginning of the twentieth century, American women were going to Europe, studying in the academies, and becoming professional, and then coming back here and, as I’m saying in my text that will be in the exhibition, they wind up giving private art lessons to kids or other women because the galleries won’t show their work, the critics are not reviewing their work. At the end of the nineteenth century, beginning of the twentieth century, there were a couple of exclusively women artist exhibitions in Europe. But the exhibitions were only of drawings.

AN: Within the exhibition itself are there themes?

AL: Yes. We’re looking at photography first because where American women artists really took hold very strongly at the end of the ’20s and the ’30s and into the ’40s and beyond was in photography. You have people like Dorothea Lange, Berenice Abbott, Imogen Cunningham. No one was doing better photography.

AN: Do you think women had an in with photography because people didn’t really think photography was an art form?

Arnold Lehman.

COURTESY PHILLIPS

AL: Exactly. They were exploring a new world. The men were still off in their studios painting away and chipping away at marble and steel and whatnot, manly things. And women were looking at a whole new area in the visual arts. And then you look through the ’40s, ’50s, and women changing from looking at more modernist things to becoming more socially engaged, socially conscious. Diane Arbus, for instance, looking at marginalized individuals and groups. Women looking at African American communities and photographing and treating them very, very positively. In a way, it’s with this wedge of photography that women started to actively be recognized in painting and sculpture and the first artist that I look at, or that’s in the exhibition, in terms of painting, is Marguerite Zorach, who is working in kind of a fauvist, modernist style. There’s a beautiful still life in the show from her.

AN: The name Zorach is familiar to me so I must know the husband’s work.

AL: Of course. William Zorach. But people don’t know Marguerite Zorach.

AN: So how old was she in 1945?

AL: I would guess she was 25 or 30. Again, an artist who I really didn’t know, and that was Mary Callery, who was a sculptor. There were many sculptors in Europe, but in America it’s very hard to find.

AN: Where is the work? In collections?

AL: It’s in collections, there’s work in the Museum of Modern Art that I think used to be in the sculpture garden, I don’t know if its still there.

AN: And were these women very prolific?

AL: It varies. The photographers were. I think Marguerite Zorach was. Mary Callery I’m not sure. And then we certainly go on to the artists of the 1950s and ’60s, people as early as Louise Bourgeois in the late 1950s, the beginning of beautiful works by Agnes Martin, we have a gorgeous drawing by Agnes Martin.

AN: So what are some your great finds that we’ll see in this show?

AL: There’s a spectacular Howardena Pindell. Spectacular. One of her truly great paintings. Truly spectacular. And very large, so next week I get into the installation issue. And it’s a treat, by the way, here I was a museum director and, as you know, I hovered over exhibitions but getting into the actual details of it is a lot of work, which a lot of other people did when I was at Brooklyn or [the] Baltimore [Museum of Art]. But I get to do this, which is fun, and I have two great colleagues working with me. So, that Howardena Pindell, fabulous. Certainly, among the very best I’ve ever seen. Another is a spectacular mid-1980s work by Jenny Holzer. A spray painting, which is very aggressive. Terrific. There is an incredibly young woman, Thenjiwe Niki Nkosi, who is American but lives and works in South Africa. There’s an amazing painting that relates the natural world to the man-made world and it’s very much, I think, about what’s happening in Johannesburg right now. It’s just breathtakingly beautiful. If it works out, we have a painting that’s literally being painted as we speak by a young Latina artist, Bianca Nemelc, who I think is terrific, literally of the moment.

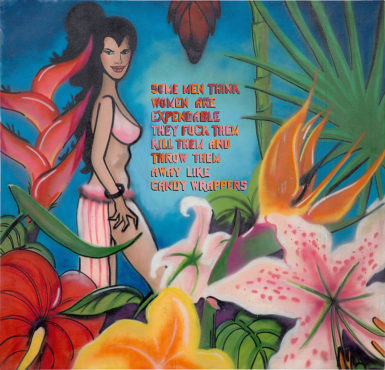

Jenny Holzer and Lady Pink, Some men think women are expendable they fuck them kill them and throw them away like candy wrappers, 1983-84, spray paint on canvas.

© 2019 JENNY HOLZER, ARTISTS RIGHTS SOCIETY (ARS), NEW YORK

AN: So that will be the most recent piece, and what is the earliest piece?

AL: The earliest piece is going to be probably either Berenice Abbott or Dorothea Lange. I tried to install the exhibition chronologically. It doesn’t always work, and it doesn’t always allow us to highlight a work that needs highlighting. Initially, I was going to do the exhibition in a non-chronological fashion because there are so many things that work incredibly well.

AN: Sure, you could just see what looks good next to what.

AL: Wouldn’t that be wonderful? But I’m too much of an art historian to allow myself to do that, and I don’t think it’s as much of an educational opportunity for our visitors. I’m also trying to teach a little bit with this. There are lots of great things by all the names, wonderful piece by Ghada Amer, terrific piece by Lynda Benglis.

AN: Other highlights?

AL: There’s a wonderful older neon piece by Deborah Kass that’s dedicated to Louise Bourgeois. A great Jackie Ferrara tower. There’s a great Katherine Porter painting, very early, I think late 1960s. I have a great Grace Hartigan painting in the show which is another person whose name is not familiar to people, even people who are knowledgable about the second wave of Abstract Expressionism.

AN: It’s all Lee Krasner now because of the retrospective.

AL: You know, we did a Lee Krasner show 20 years ago at the Brooklyn Museum and it was spectacular. I had a huge Lee Krasner that Brooklyn owns hanging in my office. I adore Lee Krasner’s work, and we worked with her niece, who’s now since died, who was wonderful in helping us with that. Lee was a great painter.

AN: Aside from the obvious ‘looking at under appreciated women artists is in the air’ kind of thing, what was the inspiration for this show? You mentioned the voting rights…

AL: I worked for close to twenty years within an environment, the Brooklyn Museum, where feminist art was very important. Your own institution with a feminist art center and with constant educational programming in terms of women’s art and feminist art. And we used to think, in a way, of the institution as one that is heavily indebted to its feminist issues, [of] which, I always believed, equity was the primary issue. So, the issue of equity, to me, crosses all boundaries in terms of making sure that we work with artists of color, not only appropriately but with impact, and with women, again with a lot of impact. You will see in this exhibition a lot of feminist artists from Hannah Wilke to Mary Beth Edelson to Barbara Bloom. On and on and on. Judy Chicago. In the beginning, I was going to do an all-feminist exhibition, but then I realized I want it to be broader than that.

AN: And now you are at an auction house.

AL: The difference of course is that this is a selling exhibition. So, not only do I have to convince the owner that I’d like to borrow it in the exhibition, but it needs to be borrowed and it needs to be offered for sale.

AN: And has that been a challenge for you to transition from the museum world to working in that way?

AL: No because I always put as the goal getting people to see great art. Just because it’s for sale doesn’t mean it’s any less worthy, but it does mean that you have to convince the consigner, who might love the work, and in a museum exhibition knows they it will come back after three months, three years if the exhibition travels. So, we have to find those people, whether they’re galleries, individuals, foundations, whatever, who not only know that they have something terrific, but are willing to part with it. And artists individually—I’ve worked with a lot of individual artists who either don’t have galleries, don’t want to have galleries, or the relationship with the gallery is such that they have their own work and the gallery has work.

AN: What would you say to someone who is critical to the idea of this show and says, ‘How good can it be if you can only get things that are for sale?’

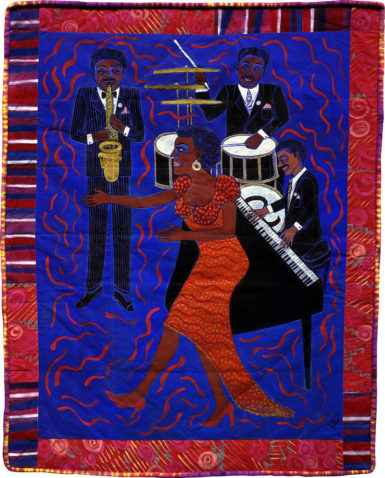

Faith Ringgold, Jazz Stories: Mama Can Sing, Papa Can Blow #6: I’m Leavin in the Mornin, 2004, acrylic on canvas with pieced fabric border.

© 2019 FAITH RINGGOLD/ARTISTS RIGHTS SOCIETY (ARS), NEW YORK/COURTESY ACA GALLERIES, NEW YORK

AL: I would say come and see the show. Part of the issue, and I’m saying this very candidly, is to convince some galleries and some artists individually that there is no stigma about showing work at an auction house. Our selling exhibition is no different than a selling exhibition in thousands of galleries all over the world. Our exhibition is longer, it’s going to be there six weeks. Everything stays the way it is, we don’t pluck things out and put things in. I hope people would agree that they’re installed beautifully. We have a gorgeous online catalogue for the exhibition, and the one thing that we do do that a very substantial number of galleries in the United States and elsewhere [don’t], is we reach a lot more people. We have 10,000 clients and we email to I don’t know how many people. And for “American African American” [which was on view at Phillips last year] we had thousands of people coming in to see it, we had almost 900 or 1,000 people, something like that, for the opening. I have to explain very often to people, no this is not an auction, this is an exhibition, like anywhere else.

AN: You were director of the Brooklyn Museum for almost 18 years. They have a terrific education department.

AL: If it weren’t for the education department over half a century or more, I’m telling you the Brooklyn Museum wouldn’t be there. The education department has been a glory of the Brooklyn Museum, with that amazing collection and that amazing building, the educators, in thick and thin, amazing. And they’re like missionaries, they have sent out educators who get hired by museums all over the country to work in those education departments because the training that they got at the Brooklyn Museum was just amazing. And they’re still doing it.

AN: There was this flyer circulating in Park Slope recently about this enormous building that’s been proposed and the conservationists at the Botanic Gardens, which as you know are right next door to the Brooklyn Museum, are concerned because there will be shade where there shouldn’t be, and it’s going to affect their plants.

AL: The battle, there are so many battles over the issue of light in Manhattan, but that was a battle of taking light away from people, who could fight back. This is about taking light away from plants that have been there for a hundred plus years.

AN: It’s really tragic, and the plants affect the insects and then it all goes down the line and…

AL: Pretty soon you’ll have crocodiles on Washington Avenue and Eastern Parkway! I’m telling you.

AN: Well, they’ll make them pay high rent.

[ad_2]

Source link